Pea Soup

September 17th, 2011

Earlier this week, I made a gigantic pot of ‘French Green Pea Soup’, from a receipt originally published in Eliza Leslie’s 1840 masterpiece, Directions For Cookery, In Its Various Branches. I found the digitized book on one of my favorite websites, Feeding America: the Historic American Cookbook Project.

This yielded nearly two gallons of soup. I didn’t intend to make quite so much. But I made the mistake of following the quantities as written, and ended up with enough to feed the average mid-19th century household or a small army.

It was an astonishingly easy receipt and required very little adaptation. I started with four bags of frozen green peas — approximately a quart each, or maybe a little more — and two sweet onions.

I threw in generous handfuls of fresh herbs: mint, marjoram, and basil.

Then I covered the peas, onions, and herbs with as much water as the pot would hold. It called for a full gallon, but there wasn’t quite room to put it all in. Makes you wonder about pot sizes in 1840…

Such a large pot of soup took a long time to boil. But once it did, I turned it down and let it simmer uncovered until the peas fell apart. Then I cheated and resorted to my immersion blender. By rights, I should have mashed the peas against the side of the pot. I rather messed up the spinach part by choosing frozen spinach, which behaved more like an additional herb than would have the juice from fresh spinach. And I forgot to strain the soup too — though I have a feeling that step was rendered less necessary by use of the immersion blender. The butter rolled in flour seems like a shortcut to a roux. I usually make vegetable soups without additional thickening, but the butter was a nice addition.

And the result — thoroughly unappetizing in a photograph, but surprisingly delicious; with a pleasant kick, thanks to the cayenne pepper. I think I will try this again, perhaps quartering the ingredients, and sticking closer to the original methods (fresh peas, fresh spinach, no electric blenders, etc.).

19th-C. Hand-Work Circle: Crochet Workshop

September 14th, 2011

I’m going to share my recent obsession for mid-19th century crochet edgings next month at our first fall meeting of the New York Nineteenth Century Society Hand-Work Circle. I hope you’ll plan to be there!

Saturday, October 1, 1 to 3 p.m.

At the Ottendorfer Library, 135 Second Avenue in ManhattanJoin the New York Nineteenth Century Society’s Hand-Work Circle for a presentation featuring techniques for recreating crocheted lace from historic patterns. Afterwards, you’re invited to hone your own crochet skills (please bring a spool of crochet thread — not yarn — and an appropriately sized hook), or simply sit back and enjoy the company of fellow enthusiasts while you work on your latest hand-work project. Free, but space is limited. RSVP to eva@nineteenthcenturysociety.org. Use of library space by the New York Nineteenth Century Society for this program does not indicate endorsement by The New York Public Library.

Earlier this month, I finished my second fancy petticoat with a hand-crocheted trim based on an 1855 pattern from Peterson’s. I guess I’m a glutton for punishment, for I’ve already begun another length of crochet trim, also from a Peterson’s 1855 pattern. This one is quite a bit more elaborate. And time consuming. Plus, I think it’s fussy enough to stand a little embroidery on the accompanying petticoat skirt…

So far, I’ve just got the header done, and have begun adding the central motifs, spaced along the length every couple inches or so.

I really enjoy adapting crochet patterns from the past. It helps so much when there’s a picture to go along with the written directions, since so much is up for interpretation in crochet. I also like the way crochet can be used to imitate other styles of lace — that’s partly the reason crochet caught on in the first half of the 19th century. We’ll discuss the history of crochet, as well as techniques for finding and using historic patterns, at the upcoming Hand-Work Circle.

Here are a few other crochet projects from my past:

This is the neck and sleeve of a chemise, made to be worn under an 1870s ballgown. I made up the pattern myself, based on a picture in Weldon’s Practical Needlework. I was in too much of a hurry to work through the pattern properly!

Ignore the top two, they’re both tatted (and very poorly). The bottom one is a crocheted insertion, from a modern pattern.

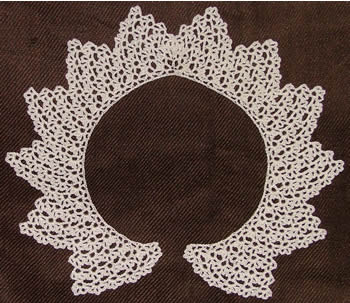

A completely apocryphal crocheted collar — just a bunch of repeats of a mid-20th century edging. Still, it’s rather pretty, and would look well on a dress…if I ever actually finished one, that is!

Once I finish my current crochet trim, I think I’d like to try something with really fine thread. I have a set of teeny weeny hooks, imported from Germany, that don’t get nearly enough use. My size 10 steel hook (just about perfect for bedspread-weight cotton thread, which Peterson’s says is right for a petticoat) has seen so much activity lately, it’s changed color where my fingers go and started to bend at the top!

Let ’em Eat Cake

September 10th, 2011

Tonight, over dinner (in a restaurant — I’m staying clear of the kitchen for a while), I totted up how much baking I’ve done this week. 196 tart shells and 225 cupcakes later, I think I’m ready for a break.

In case you’re curious, here is my cupcake receipt, from a reprinted edition of the “Everyday Cookbook” from Lord & Taylor, circa 1865. I don’t have the original text, so the following is in my own words.

California Cake

Two cups sugar

1 cup butter

1 cup milk

Two eggs, slightly beaten

1 tablespoon baking powder

3 cups sifted flour

Flavoring, fruit, or nuts to tasteCream butter and sugar. Beat in eggs, milk, and flavoring. Sift flour and baking powder. Beat flour into wet ingredients in three parts, beating until smooth between each addition.

Bake at 350 until done. Makes 2 cakes or 75 mini-cupcakes.

I have no idea what makes this cake particularly Californian. It’s very good though. Moist, yet light, with a surprisingly coarse crumb. My favorite flavoring is rosewater and cinnamon. But vanilla or almond is nice too. I’ve made it into a few layer cakes (with raspberry jam in the middle) over the years, but usually stick to cupcakes. Regardless of shape, size, or historical accuracy, my favorite icing for California Cake is butter-cream. Rosewater butter-cream. Yum! Like eating a bouquet or drinking a bottle of perfume. But in a good, non-poisonous way.

Brignal Ballad

September 9th, 2011

It’s always a good day when you discover a new song, especially one published in 1829, with words by Sir Walter Scott and arrangement for voice and piano by J. F. Hance!

O Brignal Banks Are Wild and Fair: a Scotch Song

O Brignal Banks are wild and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

And you may gather garlands there,

Would grace a summer queen.

And as I rode by Dalton hall,

Beneath the turret high,

A maiden on the castle wall

Was singing singing merrily.

“O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.”O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green.

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.If maiden, though wouldst wend with me,

To leave both tow’r and town,

Thou first must guess what life lead we,

That dwell by dale and down.

And if thou canst that riddle read,

As read full well you may,

Then to the greenwood shalt though speed,

As blithe as queen of May.

Yet sung she “Brignal banks are fair,

And Greta woods are green;

I’d rather range with Edmund there,

Than reign our English queen.”

I found scans of the folio, published in New York by Dubois & Stodart, on this website.

I’ll wager you already know who Sir Walter Scott is, and perhaps have even read some of his work. I prefer his poetry (it seems to wear its two-centuries a bit better), though to be fair, I’ve only read one Scott novel. Here is the Baronet (made 1818) himself in an 1822 portrait by Raeburn. He appeals to the Scott in me.

But odds are you haven’t got the faintest idea who J. F. Hance is. Neither did I until last year. It turns out Mr. Hance was an American composer, active during the early Romantic period, right about the same time as Sir Walter Scott. History has obscured most of his works, and perhaps deservedly so. He is listed as an “arranger” on this piece, though there is no evidence that anyone else wrote the tune. Perhaps it’s a Scottish folk song that he kitted up for the piano forte? It’s quite pretty actually, unlike many of the things that Hance did take credit for writing…

I first ran into J. F. Hance at the museum where I work. A book of piano lessons was found in the collection, owned by the family who once lived in the house. It’s an obscure pedagogical work called Instruction in the Attainment of the Art of Playing the Piano Forte, comprising lessons in basic music theory, 15 rather quixotic etudes, and two mediocre songs. The author is none other than J. F. Hance. In spring 2010, I reproduced the book (hours of wrangling with Photoshop and rendering in Illustrator to get printable page images). The etudes and songs were then recorded on the museum’s recently restored 1840s rosewood piano forte. This instrument, also owned by the family, still sits in the same parlor where it’s been since the mid-19th century. And it’s almost certain that the pieces in the Hance book were played on it by the daughters!

Thrill of thrills, after many attempts to find a more accomplished musician, I ended up playing for the recording. It makes sense in a way, since the women who played the piano when it was new were certainly not professionals. I’ll never forget the feel of the keys, or the sound of the notes echoing through the room. In some ways, it’s as close as we’ll ever come to hearing what they heard, so many years ago. Same room. Same piano. Same song.

Following the advice of our excellent conservator, we decided not to continue playing the piano at the museum. It’s simply too fragile, and continued use means that the original parts will eventually have to be replaced by modern fabrications. This instrument is too much in tact, too well-provenanced, too rare. They do play the recording for visitors though, and soon it will be available for purchase on CD.

Queen of Tarts

September 8th, 2011

I guess I do make a lot of tart shells. This week alone, I’ve baked nine batches, a grand total of 204 shells. Don’t laugh, there were extenuating circumstances. And I only kept one set for myself. We’re still eating them — three of the dozen were filled with cheese and glazed onions. The rest have been slowly but surely spread with raspberry jam and eaten for elevenses (I can’t seem to get through a morning at work without a cuppa and a nibble) or for dessert.

Here’s tonight’s ration. I took mine with a mango black tea latte. He had his with a mug of China green tips. After these, there are just two more.

I can’t tell you how thrilled I was when someone asked for my tart shell receipt yesterday. So here it is, in all it’s glaring modernity.

Not-19th-Century Tart Shells

Makes 24 mini shells, or 12 standard-cupcake size shells.1 cup flour

1 stick butter

3 oz cream cheeseBring butter and cream cheese to room temperature — they will be very soft. Blend butter and cream cheese with a fork or a mixer. Whip a few seconds, until very smooth. Sift in the flour and mix with a fork or pastry blender. Form a ball of dough as soon as you can, adding a little flour if needed. The less you work the dough, the more tender the result!

Wrap the ball of dough in a plastic bag and let it rest in the refrigerator for at least an hour, or up to 24. Cut in half, and in half again. If you’re making mini shells, cut each piece once more in half, for a total of 8. Pull each of the four, or eight, pieces of dough into three parts. Put the little balls of dough into an ungreased muffin tin. Using your finger, spread the dough to cover the bottom and sides of each muffin. You may need to let the dough warm up a little to make it easier to spread.

Prick the bottom of each shell with a fork. Bake at about 400 degrees for 10-15 minutes, or until the edges are golden brown.

This is a totally modern recipe. I found it on the internet a few years ago, shortly after I began catering tea parties. It is fail-safe, quick, and easy. Also, it produces a tender, rich, flaky crust. Butter alone is harder to manage, and always seems a little tough. My Gram, whose pie crusts are legendary for their blue-blooded delicacy, taught me to use Crisco. But after the whole hydrogenation scandal, I’ve tried to avoid it.

How did they manage in the 19th century, you ask? Surely they didn’t just endure tough “paste” (Victorian for pie crust) until the advent of Crisco? They used lard. Which I’ve never tried because it too is now hydrogenated, at least the kind they sell in my local market.

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »