Hateful Heroines

July 3rd, 2011

What is it with Thomas Hardy and heroines so unsympathetic that we actually cheer their downfall? I thought Bathsheba Everdene was a pill (at least until the very end), but I must say that Eustacia Vye takes the cake. Written 4 years later, perhaps Eustacia was the product of the writer’s growing confidence in his ability to sell novels despite their being about truly horrifying people.

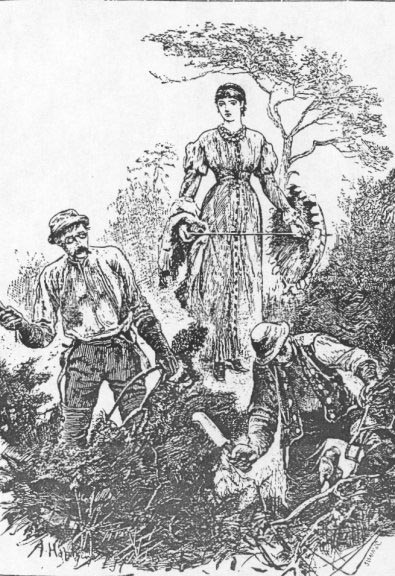

An original illustration, showing Eustacia’s cruelty.

I read Return of the Native (1878) on the plane home from California, and found myself repelled by nearly all the characters, with the possible exception of the insipidly sweet “Tamsie”, but by none so completely as Eustacia. I think it was Hardy’s gift to shine unflinching daylight on the very worst in the name of representing things as they were, rather than to hold up the dim and flickering candle by which his predecessors attempted to show us the often imaginary, nobler side of man’s nature. I have a perverse pleasure in watching the suffering of his characters, as I can’t help enjoying the feeble death throes of a roach I’ve just stepped on. I wonder if Hardy felt the same way while he was writing them? Or did he love them as fellow sinners and fellow countrymen, blaming their shortcomings on the darkening of the world as it slipped away from rural simplicity?

Although I continue to be entranced by Mr. Hardy’s quaint viewpoint, I am taking a breather before diving into The Mayor of Casterbridge or Under the Greenwood Tree, both of which are waiting patiently on my shelf (the one a paperback purchased last week, the other a 19th-century edition and gift from a dear friend).

Sadistic Feminism

March 14th, 2011

I have now read two novels by Thomas Hardy, and am convinced that, within the confines of accepted thought of his time, he was a rampant feminist. I may change my tune when I’ve had time and inclination to read further into his novels, but so far, both Bathsheba and Tess strike me as powerful advocates for their sex. M’hap not so much on their personal merits — the one a self-centered brat, the other an emotional simpleton — but as examples of the senseless harms perpetrated on the weaker sex by an unsympathetically masculine world.

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles particularly, one finds very little patience with any of the male characters. The stories of the women, from Tess and her relations, to the girls she labored with at the dairy and later the starve-acre farm, are all finely drawn and their trials wrought with such pathos as to tug at the heart of even the most chauvinistic reader. On the other side, we have only her shiftless father, lascivious “cousin,” and starry-eyed stripling of a husband. The sin that Tess must absolve with heart’s blood is caused by one man and shunned by another, and her ultimate punishment is exacted by a society founded on the prejudices of men.

Rather than rail at his readers, Hardy takes the subtle approach of engaging our sympathy. He presents the case without argument, trusting in the intelligence of some at least to make the leap. Or do I read too much into his fine storytelling? He could have simply written what he saw, and it is only my post-feminist sensibility that perceives any preference in the narrative.

I suppose I should first enlarge my base from which to pursue such conjecture by reading more of Hardy’s works. But I simply cannot undertake such just at present. Two in a row is more than anyone should have to take. Suffering is as suffering does. After finishing Tess yesterday, I was tempted to pick up Sons and Lovers, but forbore even that much and chose North and South by Mrs. Gaskell instead.

Hardy Explains Himself

February 25th, 2011

I’m about halfway through Tess of the d’Urbervilles, but I couldn’t resist sharing this line:

“the chronic melancholy which is taking hold of the civilized races with the decline of belief in a beneficent power.”

I’ve finally traced the well-spring of the despair that weaves through late 19th and turn of the century literature. And my long-time suspicions have been proven true!

You may laugh at my naiveté, but first consider that I missed out on all those comparative literature courses you had to suffer through. I’m seeing all this with fresh eyes and can’t help being a little bit excited.

For the record though, Tess is harder to read than Far from the Madding Crowd — it’s obviously further down the road of Hardy’s artistic development, and he has dared to put completely sympathetic characters in the path of dire and senseless misfortune. Harder to read isn’t always a bad thing though. Tess seems a more complex, complete work. And, so far at least, it abstains from self-consciously poking fun at itself, which, though fun to read, is the mark of an unsure author.

Ten points if any of you Jimmy Webb fans can figure out why I’m including this Art Garfunkel video in tonight’s posting.

An Unexpected Ending

February 6th, 2011

For the past week I’ve been reading Far from the Madding Crowd. Until today, it was my considered opinion that the chief of Thomas Hardy’s talent lay in his singular ability to invent unsympathetic characters and subject them to well-deserved tortures for more than 400 pages at a time. At first I was merely disgusted, but eventually I began to enjoy the idiotic wranglings of Bathsheba and Sergeant Troy and Farmer Boldwood. I even sneered knowingly at Shepherd Oak’s doormat-like inclinations. At least the pace of the book was agreeably quick — with the protagonists spinning quickly downward in their rush to ruin.

But then the ending drew near, and I turned the pages feverishly waiting for the shoe that never dropped. What came instead was one of the most delightfully wry, pulled-punch endings I’ve ever read. Unlike Great Expectations, where the ending most of us know is famously tacked on, this one clearly belongs (in my opinion at least). And it proves that Hardy knew I was laughing at his melodramatics, and was laughing right back at me all along. As usual, I won’t tell you a morsel more for fear that you may decide not to read it for yourself.

We walked past Housing Works (a second-hand bookstore whose profits go to help New Yorkers living with AIDS — as if I needed yet another reason to buy books) on our way back from an Orchard Street excursion this afternoon. As soon as I knew we were going to stop, I decided to keep my eye out for a copy of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Fate must have been on my side, for there, on the fifty cent book rack (as if you needed yet another reason to visit Housing Works yourself), was a battered copy of the very text I sought. Ridiculous as it may seem, there was a 30 percent sale in effect, so the actual price was even less.

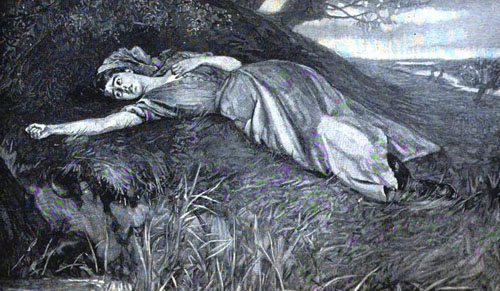

“Hands Were Loosening His Neckerchief” by Helen Patterson Allingham, Cornhill Magazine (February 1874)

I am eager to read more of Hardy. I enjoy his easy mix of rich, descriptive prose and head-whirling action. Stilly drawn scenes of English country life — in his fictional county of Wessex — offer a bucolic backdrop for a plot that is anything but expected. I have been used to narratives where every move is contemplated and hinted at ad nauseum for chapters (perhaps an effect of early publishing methods, where books were released in installments), so it’s a refreshing change to find such drastic occurrences in quick succession.

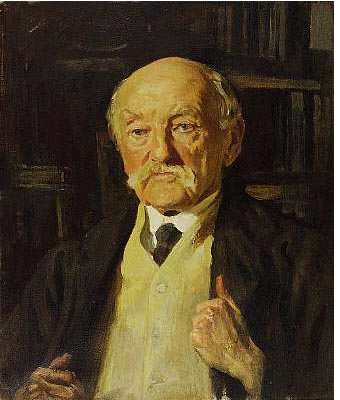

Thomas Hardy by Reginald Eves

Writing in the 1870s, Hardy, like Henry James and Edith Wharton, seems to be foreshadowing modern literature. He has not given up the conventions of the 19th century novel, but he steers clear of the moralizing and judgment (except by proxy, through his characters) that was so rampant a few decades earlier. Also like James and Wharton, Hardy seems to write as an observer looking back, almost longingly, to a simpler time — at least as seen through his thoroughly industrialized eyes. I see hints of the bleakness that bothers me in many fin de siecle and early 20th century works, however there remains a certain reverence that I find most agreeable.