HSF #3: Under it All

May 14th, 2013

Boy is this a belated post. The deadline for this challenge was February 11. That’s MONTHS ago. Oops. But here it is in the spirit of better late than never (when you try to juggle as many things as I do, this becomes one of your favorite phrases)…

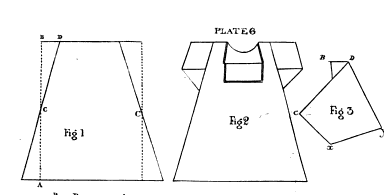

I made a early-mid-19th century shift exactly by the book. That is, following the directions in the Workwoman’s Guide (1838) to the letter. I mostly used the written directions and measurement charts, but it’s nice to have illustrations for reference as well, like plate 6, shown here. Don’t worry if you can’t find the illustrations when you read the Guide on Google Books — they’re all at the end.

After a little hesitating, I decided to break into my stash of NYC linen. I selected a piece with a fairly loose weave — not at all historically accurate, especially since the warp is made of much tinier threads, throwing the balance completely off. But it seemed like the best approximation of the “stout linen” recommended for shifts “for poor children.” (I realize that makes no sense at the moment, but I’ll explain what I’m working on eventually.)

The fabric was 60 inches wide, give or take a few after I shrunk it twice, so I was able to cut it in half and scrape out enough to make two shifts in the “first size” (aka smallest) with a single length. I cut it “to a thread,” which is the laborious process of pulling out a thread and cutting along the empty line to make sure you stay on grain — alas, linen cannot be torn like cotton. Then folded my length of fabric at the shoulder and basted up the selvedges so they’d stay together as I cut off the gores (see figure 1).

I was reminded how tricky gussets can be when you’re sewing and felling. I’ll admit here that I completely messed up the first sleeve. A quick refresher from a selection of mid-19th century sewing manuals helped me get the second sleeve nearly perfect.

Once I’d cut out all the pieces — which was pretty easy since they were just rectangles — it went together very quickly. The edges were simply hemmed, with the exception of the neckline, which got double-turned and sewn for extra strength.

I forced myself to mark the shift at the back neckline with red embroidery thread. Workwoman’s Guide doesn’t mention ink in its section on marking, so I gritted my teeth and made with the magnifying glass. I opted for only my initials since using the current year would look funny, and it didn’t feel right to lie about the year either. I mean, with all that hand-sewing and accurate construction, it might get mistaken for an antique, right?

I was a little nervous about making the smallest size. I mean, I may be fairly trim for a 21st, century person, but I’m also half a foot taller than the average woman of 1850 and probably have a bigger — or at least longer — bone structure overall. I did end up adding 4 inches to the length, figuring that’s about how much extra length is in the part of my body covered by the shift. To my surprise, the shift is actually quite roomy. With the exception of the sleeves, which JUST fit my not-particularly-muscular upper arms.

The neckline is especially large. At first I thought I’d made a mistake. But my measurements were perfect. And then I thought there might be a drawstring coming later on in the directions. But nix on that as well. So I am left with three possibilities.

- Women in the mid-19th century were universally better endowed than myself (which isn’t surprising considering what I’ve noticed in the early 21st century).

- They made all their clothes really big because repeated washday boilings were bound to shrink them considerably.

- It’s time to reevaluate the way I interpret “fit” of historic undergarments.

Number 3, while it may seem unlikely, and definitely involves eating at least a sliver of humble pie, does fit with my experience recreating the Regency apron-front dress from Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion I. It’s also supported by some of the paintings I’ve been working from for my latest project. And here I thought the artists were being salacious by portraying women with their shifts falling off their shoulders. But maybe they just slipped on their own…

Just the facts, Ma’am: Workwoman’s Guide Shift

The Challenge: #3: Under It All

Fabric: 60″ wide hopelessly modern linen with an unbalanced weave

Pattern: From the written directions and diagrams in the Workwoman’s Guide, 1838

Year: 1838 (this shape remains accurate through the mid 1850s)

Notions: 100% cotton thread, red cotton embroidery floss

How historically accurate is it? I’ll give it 95%. It’s entirely hand-sewn according to mid-19th century plain sewing directions, with attention to specific techniques for shift necklines and gussets from the Workwoman’s Guide and other sources. The construction is as accurate as possible given the width and weave of the modern fabric I had to work with. Because of the fabric, I had to sew and fell the gores onto the bottom of the shift body, whereas if I’d been using proper fabric, I would have sewn them selvedge to selvedge. This time I broke out my 100% cotton thread, along with the beeswax and lots of extra patience.

Hours to complete: Probably about 15. It’s hard to tell when you sew in odd moments, like before breakfast, or while you’re playing dummy at the bridge table…

First worn: This afternoon, to take pictures. It will ultimately figure in a much larger project that is currently stamped TOP SECRET (mostly because I love being dramatic).

Total cost: About $10. I don’t remember exactly how much I paid for the linen, but it was probably about $7 a yard. The cotton thread wasn’t cheap, but I barely made a dent in the spool.

Stitch Not In Time

March 4th, 2011

Alright, alright, I’ve learned my lesson. Don’t make hand-sewn undergarments out of plain muslin. It’s oh, so tempting at less than $2 a yard (actually, it might as well be free — I’m still sewing through a bolt of white cotton muslin that my mother bought for me a decade ago). But look what happened to the chemise I made last year. I’ve only worn it three or four times too.

I think it might have ripped while I was fitting my new stays, twisting around this way and that, trying to slide into them without unlacing. Drat!

Always one to look for the silver lining, I have decided to use this as an excuse to practice my mending. Many of the manuals that I used to learn 19th-century hand-sewing have extensive sections on mending, including this catechism from England’s Finchley School manual Plain Needle-Work, in All Its Branches, 1852:

PATCHING.

Q. You have told me how you would manage a sheet, or any large coarse article; but should the linen, cotton, or whatever the material may be requiring a patch, be of a finer description, or printed in colours, how would you proceed?

A. I would cut the piece with which I intended to repair, exactly to a thread, and place it on the decayed or worn part, to a thread also, and on the right side; taking care, should the article have any pattern, to fix the patch so as to make the parts of the pattern correspond.

Q. “What next?

A. I then tack the patch on slightly, to keep it ia its place, and sew it at the edges in the manner of a hem, taking care to manage the corners neatly.

Q. And then?

A. Having made the cloth very flat and smooth, I carefully cut out the old piece on the wrong side, leaving sufficient to form a hem, the same as in patching a sheet.

Q. How do you manage to make the hem sit neatly at the corners?

A. I nick it a little, at each of the four corners, carefully turning-in the raw edges, making allowance for turning them in, and then proceed with the hem.

And just in case I’m tempted to put speed ahead of quality (especially since I need to rip out the armhole facing and hem it back down again over the patch):

“Patches should always be well shaped, and basted on perfectly even; a round, angular, or slanting patch, is the sure sign of a slut.”

The Girl’s Own Book, by Lydia Maria Child, 1853

Anyone having a sale on Kona cotton broadcloth? Or should I finally break into that stash of cream linen for my next chemise?

Past Projects: Shift

February 13th, 2011

This garment, my first (and only, to date) 1850s shift, aka chemise*, is a bit of a jumble. It looks fine from a distance, but the fact is I alternated between 5 different sets of directions, which occasionally contradicted each other outright. There were also a few spots (mostly around the neckline) that every set of directions glossed over, so I simply guessed. I need to start visiting costume collections to look at extant garments to see all those little details!

The 1850s was a time of change for most female undergarments, many of which had remained stable in shape for decades previously. Last summer I made a shift from the 1838 Workwoman’s Guide. It was much more simply cut than this one, and ended up being enormous because I made it according to one of the larger sizes given. I gave it away to a photographer for use as a prop.

I do plan to experiment some more with the Workwoman’s Guide patterns (and will probably give away the results), until I get the sizing right. Even though the shape they take is old fashioned compared to illustrations in 1850s magazines, it’s still very much acceptable for the period. Makes sense, since many of the women who were sewing shifts in the 1850s had learned to make them a decade earlier.

As you’ve probably guessed by my previously stated predilections, this shift is entirely hand sewn. I embroidered the scalloped band, based on the simplest pattern I could find in Godey’s.

*Like the shape of the shift, the name also changed in the 1850s. By the end of the decade most people in America and England had adopted the French moniker Chemise.