Our Lady

December 12th, 2012

Our local hamlet is putting on a Christmas Musicale later this month. In addition to singing a shaky soprano in the choir, I’m also taking part in a girls trio doing Ave Maria. We’re using Schubert’s setting, since it’s probably the most familiar these days — thanks to Frank Sinatra, et al.

What I didn’t know was that Schubert, who composed the iconic melody and cascading arpeggio accompaniment in 1825, didn’t write it for the Latin prayer. It was part of his seven-song cycle for a German translation of Sir Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake. I’ll pause a moment while that sinks in. Or maybe you already knew, and I am the only one floored by this revelation, courtesy Wikipedia.

Illustration from Lady of the Lake

Perhaps it hits me particularly hard, since Lady of the Lake is one of my absolute favorites.

He goes to do what I had done,

had Douglas’s daughter been his son…

Doesn’t it just send thrills up your spine? Apparently, Schubert wrote Ellens dritter Gesang (Ellen’s Third Song) for a point in the poem where Ellen prays to the Virgin Mary on behalf of her embattled Highland clan. Here it is in English:

Ave Maria! maiden mild!

Listen to a maiden’s prayer!

Thou canst hear though from the wild;

Thou canst save amid despair.

Safe may we sleep beneath thy care,

Though banish’d, outcast and reviled –

Maiden! hear a maiden’s prayer;

Mother, hear a suppliant child!

Ave MariaAve Maria! undefiled!

The flinty couch we now must share

Shall seem this down of eider piled,

If thy protection hover there.

The murky cavern’s heavy air

Shall breathe of balm if thou hast smiled;

Then, Maiden! hear a maiden’s prayer,

Mother, list a suppliant child!

Ave Maria!Ave Maria! stainless styled.

Foul demons of the earth and air,

From this their wonted haunt exiled,

Shall flee before thy presence fair.

We bow us to our lot of care,

Beneath thy guidance reconciled;

Hear for a maid a maiden’s prayer,

And for a father hear a child!

Ave Maria.

The German pronunciation is a bit beyond me at the moment, but you can bet I’m gonna learn it! I should probably try to dig up the other six songs as well. If this is Ellen’s third, that means at least two more are for soprano…

Brignal Ballad

September 9th, 2011

It’s always a good day when you discover a new song, especially one published in 1829, with words by Sir Walter Scott and arrangement for voice and piano by J. F. Hance!

O Brignal Banks Are Wild and Fair: a Scotch Song

O Brignal Banks are wild and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

And you may gather garlands there,

Would grace a summer queen.

And as I rode by Dalton hall,

Beneath the turret high,

A maiden on the castle wall

Was singing singing merrily.

“O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.”O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green.

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.If maiden, though wouldst wend with me,

To leave both tow’r and town,

Thou first must guess what life lead we,

That dwell by dale and down.

And if thou canst that riddle read,

As read full well you may,

Then to the greenwood shalt though speed,

As blithe as queen of May.

Yet sung she “Brignal banks are fair,

And Greta woods are green;

I’d rather range with Edmund there,

Than reign our English queen.”

I found scans of the folio, published in New York by Dubois & Stodart, on this website.

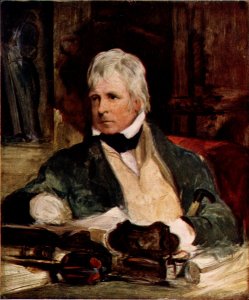

I’ll wager you already know who Sir Walter Scott is, and perhaps have even read some of his work. I prefer his poetry (it seems to wear its two-centuries a bit better), though to be fair, I’ve only read one Scott novel. Here is the Baronet (made 1818) himself in an 1822 portrait by Raeburn. He appeals to the Scott in me.

But odds are you haven’t got the faintest idea who J. F. Hance is. Neither did I until last year. It turns out Mr. Hance was an American composer, active during the early Romantic period, right about the same time as Sir Walter Scott. History has obscured most of his works, and perhaps deservedly so. He is listed as an “arranger” on this piece, though there is no evidence that anyone else wrote the tune. Perhaps it’s a Scottish folk song that he kitted up for the piano forte? It’s quite pretty actually, unlike many of the things that Hance did take credit for writing…

I first ran into J. F. Hance at the museum where I work. A book of piano lessons was found in the collection, owned by the family who once lived in the house. It’s an obscure pedagogical work called Instruction in the Attainment of the Art of Playing the Piano Forte, comprising lessons in basic music theory, 15 rather quixotic etudes, and two mediocre songs. The author is none other than J. F. Hance. In spring 2010, I reproduced the book (hours of wrangling with Photoshop and rendering in Illustrator to get printable page images). The etudes and songs were then recorded on the museum’s recently restored 1840s rosewood piano forte. This instrument, also owned by the family, still sits in the same parlor where it’s been since the mid-19th century. And it’s almost certain that the pieces in the Hance book were played on it by the daughters!

Thrill of thrills, after many attempts to find a more accomplished musician, I ended up playing for the recording. It makes sense in a way, since the women who played the piano when it was new were certainly not professionals. I’ll never forget the feel of the keys, or the sound of the notes echoing through the room. In some ways, it’s as close as we’ll ever come to hearing what they heard, so many years ago. Same room. Same piano. Same song.

Following the advice of our excellent conservator, we decided not to continue playing the piano at the museum. It’s simply too fragile, and continued use means that the original parts will eventually have to be replaced by modern fabrications. This instrument is too much in tact, too well-provenanced, too rare. They do play the recording for visitors though, and soon it will be available for purchase on CD.

Not-So-Subtle Scott

January 10th, 2011

I discovered Sir Walter Scott in August 2008, while spending four weeks flat on my back (thanks to a very silly bicycling injury), next door to a private library established at the turn of the last century. Most of the strictly literary tomes in said library were published in the mid to late-19th century, amongst whose number I found a slim volume containing an 1860s edition of “The Lady of the Lake” (1810). Later that year, I begged a copy of “Marmion” (1808) from my indulgent husband. I became so fond of Sir Walter Scott’s minstrelsy, I even proposed a theory that his rhymes don’t sound forced when read with an early 19th-century Scottish accent.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

This past summer, while accompanying the partner of my fate on a mission to find Hubert Selby’s sole cheerful novel, my eye was caught by a bargain edition of Ivanhoe (originally published in 1819 under a pseudonym). Scott, Selby — they share shelf. Having never delved into Scott’s prose, I decided to take it home with me and see how I got on. I finally picked up Ivanhoe over Christmas, still eager to avoid finishing Milton.

“Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones — It is not fair. — He has Fame & Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking bread out of other people’s mouths.”

Jane Austen, 1814 (who mentions Sir Walter Scott’s poetry in her own novel, Persuasion.)

Miss Austen may have had a point. Ivanhoe is a delightful read. It’s quicker and more exciting than his poetry, though somehow a little less satisfying from a technical point of view. On the other hand, by leaving behind the delights and challenges peculiar to verse, one can focus completely on the story. And what a surprise lays in store there for the unwary reader!

While the story is set in post-conquest England, amid the final struggles betwixt Norman and Saxon races, not to mention the doings of characters like Richard Coeur-de-Lion and Robin Hood, its real theme is antisemitism. The horrible treatment received by the two central Jewish characters, clearly not condoned by the author, incites sympathy and admiration for their strength under trial as well as disgust for the rest who perpetrate (or at least witness without protest) these atrocities. Even the conclusion seems purposefully unsatisfying, as if we are being left to question how much better might things have been without this terrible prejudice against Isaac and Rebecca.

Alfred Bunn, who “compiled” Ivanhoe into a three-act play shortly after its publication, may have had the right of things when he titled his version Ivanhoe; or, the Jew of York. He at least perceived who was the true hero of the narrative — or the father of the heroine. It also makes me wonder about the state of antisemitic feeling in 1820s England. I know there was a great deal of it towards the end of the 19th century, but Scott at least seems to have felt otherwise at the beginning. Not that he was completely free from the ugly stereotypes of the time of course, or that the book doesn’t contain many things that would surely offend today, but his sympathies were unquestionably engaged.

Here, in an early illustration, we see the brave and beautiful “Jewess” about to prove her mettle by jumping from a turret to avoid a fate worse than death.

I shan’t sport with your intelligence by telling you any more about the plot. You’ll have to read it for yourself, or at least watch the movie with Robert Taylor, Joan Fontaine, and Elizabeth Taylor (though I hear that varies quite a bit from the book).

I must say though, it is refreshing to read a book written when literary devices such as characters remaining unrecognized by their own families while wearing ridiculously flimsy disguises were still relatively fresh. The essay at the beginning of my edition (which I only read as an after thought, to confirm my own surprise at the book’s unexpected overtones) also credits Scott with providing inspiration for the Ku Klux Klan via the scene of Rebecca’s trial by the white-robed Grand Master of the Templars. Oops. I guess I revealed a bit more.

Ivanhoe, kneeling before his childhood sweetheart (an utterly insipid, perfectly blond Saxon damsel) is completely unknown, thanks to his funny hat.

Now go get your own copy of Ivanhoe, or borrow mine if you like. Make a bowl of popcorn, find a pleasant chair, light a few extra candles, and enjoy.

Great Moments in Poetry: Scott’s Heroines

December 15th, 2010

If I were to be a heroine, I’d want to be regaled in one of Sir Walter Scott’s poems.

The Lady of the Lake, 1810

Ellen Douglas, as she watches her aging father march off to save Scotland: “He goes to do what I had done, had Douglas’s daughter been his son!”

Read on…