Top-Secret Tea

July 10th, 2011

Last Friday, I finally assembled all the ingredients for my new tea blend — which we plan to sell at the museum where I work, along with a booklet of mid-19th century tea lore that I compiled and edited earlier in the year. It’s based on a 19th-century tea blend found in one of the books I consulted while editing the little monograph.

I made a pot of the tea after Saturday’s dinner, and served it along with some left-over tart shells filled with cherry preserves. My goodness, it was delicious. It’s light, smooth, delicate, flavorful, and a bit sweet, all at once. Like very good first-flush Darjeeling, only not so ethereal. I tried it first plain, and then added milk. It was lovely both ways, and I think it would stand up just as well to lemon.

In fact, it was so incredibly good that I’ve decided to keep the blend a secret. You’ll just have to buy a packet (and a booklet) from the museum’s online gift shop — as soon as I’ve put it up for sale. Once it’s available, I’ll post the link. Until then, you can salivate. And (m)ooh and ahh over my adorable cow-shaped milk pitcher.

Declension of Independence

July 4th, 2011

It’s the Fourth of July, also known as American Independence Day, the commemoration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Traditionally, Americans celebrate with parades, ceremonies, picnics, and firework displays.

In the absence of any of these typical forms of commemoration this year, I contemplated taking part in a more recent July Fourth tradition: shopping. Many of the big chain stores in SoHo are holding giant sales today, and I am in great need of a pair of purple flip flops. But…my impulse towards commercialism was easily quelled. And I spent the afternoon instead doing my laundry and lounging between loads in nearby Washington Square Park.

While at the park, I whiled away the minutes with my latest novel, The Mill on the Floss (hello George Eliot) and my long-forgotten Latin text, Dr. Smith’s Principia Latina. Since I haven’t looked at in nearly a year, I was forced to begin again. So if you ran into a young woman wearing an enormous straw hat, reciting the ablative forms of the first declension under her breath, that was probably me.

P.S. July 4th is also the fake birthday of Louis Armstrong…

Hateful Heroines

July 3rd, 2011

What is it with Thomas Hardy and heroines so unsympathetic that we actually cheer their downfall? I thought Bathsheba Everdene was a pill (at least until the very end), but I must say that Eustacia Vye takes the cake. Written 4 years later, perhaps Eustacia was the product of the writer’s growing confidence in his ability to sell novels despite their being about truly horrifying people.

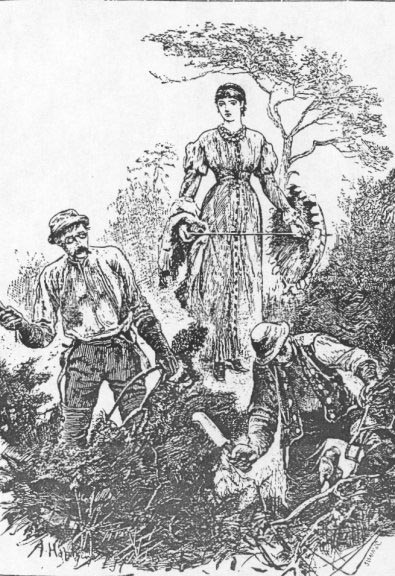

An original illustration, showing Eustacia’s cruelty.

I read Return of the Native (1878) on the plane home from California, and found myself repelled by nearly all the characters, with the possible exception of the insipidly sweet “Tamsie”, but by none so completely as Eustacia. I think it was Hardy’s gift to shine unflinching daylight on the very worst in the name of representing things as they were, rather than to hold up the dim and flickering candle by which his predecessors attempted to show us the often imaginary, nobler side of man’s nature. I have a perverse pleasure in watching the suffering of his characters, as I can’t help enjoying the feeble death throes of a roach I’ve just stepped on. I wonder if Hardy felt the same way while he was writing them? Or did he love them as fellow sinners and fellow countrymen, blaming their shortcomings on the darkening of the world as it slipped away from rural simplicity?

Although I continue to be entranced by Mr. Hardy’s quaint viewpoint, I am taking a breather before diving into The Mayor of Casterbridge or Under the Greenwood Tree, both of which are waiting patiently on my shelf (the one a paperback purchased last week, the other a 19th-century edition and gift from a dear friend).

Lemon Dream

June 27th, 2011

It seems that Meyer lemons are in season right now in California. Well actually, these marvelous trees produce fruit throughout most of the year. If you’ve never run across a Meyer lemon before, they are a peculiarly sweet and juicy varietal introduced by a fellow named Meyer (naturally) in the early 20th century. They were very popular in Edwardian hothouses — in fact, my first introduction to a Meyer lemon was in the conservatory at Rockwood Mansion. We ran out of lemons while throwing a tea party, and were permitted to raid the gardener’s prize lemon tree.

The lemon tree shown here isn’t in a hothouse though — it’s in our friends’ California garden!

During our recent trip to the west coast of America, we enjoyed Meyer lemons with shameless abandon. And we smuggled a bag of them with us on the airplane.

I wanted to share a bit of their marvelous flavor with my friends at the New York Nineteenth Century Society, so I determined to make something out of them for our June meeting. After reviewing a number of receipts, some of which I still plan to try, I finally settled on lemon cream tarts.

The tart shells I made according to modern directions. But for the cream, I used a receipt originally published in Godey’s Lady’s Book in 1854.

LEMON CREAM.—A large spoonful of brandy, six ounces of loaf-sugar powdered, the peel and juice of two lemons, the peel to be grated. Mix these ingredients well together in a bowl; then add a pint of cream, and whisk it up.

The theory is that the cream should curdle once it meets the lemon juice. But it didn’t really thicken as much as I was expecting. So I restored to whipping.

And the final result — shells lined with fresh New Jersey blueberries (’tis the season) and loaded with lemon cream. Delicious, if I do say so myself. And they were quite a hit at the meeting too!

This Is the Forest Primeval

June 25th, 2011

Practically the last book I read before leaving for California earlier this month wasn’t a book at all. It was a slim volume containing Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s immortal poem, Evangeline.

Evangeline tells the sad tale of the Acadian expulsion of 1755, when the prosperous French settlers were turned out of Canada by their new British rulers and forced to sail down the Mississippi river to their eventual home in Louisiana. I’ve long reserved a soft spot for the Acadians, ever since I sewed and wore an Acadian folk costume for my fifth grade social studies project (yes, I’ve always been like this). But this was the first time I thought to read Evangeline. It was on sale for 50 cents at Housing Works; how could I resist?

Considered by some to be Longfellow’s most famous poem (sorry Elaine), Evangeline was written in 1847. That’s less than 100 years after the historical event that inspired it! Oh, for the civilized era when tragic events were commemorated by epic poetry rather than made-for-TV documentaries. Sure, I don’t know much more about the actual facts of the expulsion, or the political machinations that were its cause. But my sympathy has been stirred to a depth that film footage with a suave voice-over could never touch. And in the end, that’s really what matters.

And yes, I cried. If you wish to know what tickled my ducts, well, you’ll just have to read the poem and find out for yourself.

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »