Fraternizing with the Enemy

November 22nd, 2011

I just watched the most amusing film, in which (I kid you not):

Kirk Douglas saves an entire wagon train and a US Army fort by sleeping with an Indian.

Naturally the Indian was played by an Italian. The bad guys were Walter Matthau and Lon Chaney, Jr. And Kirk Douglas proved that he always looks a little bit like a pirate, no matter what he wears.

Cousins Jesse & Frank

November 19th, 2011

When I was just a little girl, my maternal grandfather — whose own life is the stuff of storybooks — began researching our family history. He traced the line back to the Hite family of Bell Grove Plantation. In the end, it turns out we may not have any real Hite blood at all. But I seem to recall he did find a few other remarkable characters dangling from the family tree. Including notorious outlaw brothers Jesse and Frank James.

For someone who is likely kin to the James brothers, I’ve displayed remarkably little interest in their exploits. I don’t really know what they did to become WANTED. Or even what became of them after they were hunted down. But tonight I settled in with my latest crocheted collar project and watched Henry Fonda, John Carradine, Henry Hull, Jackie Cooper, and Gene Tierney in The Return of Frank James. If the all-star cast weren’t enough to entice you, it was directed by Fritz Lang.

The film, made in 1940, was impeccable. And I learned quite a lot about the James legend (not to be confused with the facts of the case). Perhaps it was too impeccable. I’ve been on a horse opera kick lately, watching lots of early B westerns and glorying in every dusty, over-acted minute. The Return of Frank James was a mite too polished. It felt more like Twelve Angry Men than Stagecoach. Not that that’s a bad thing, just not exactly what I was expecting.

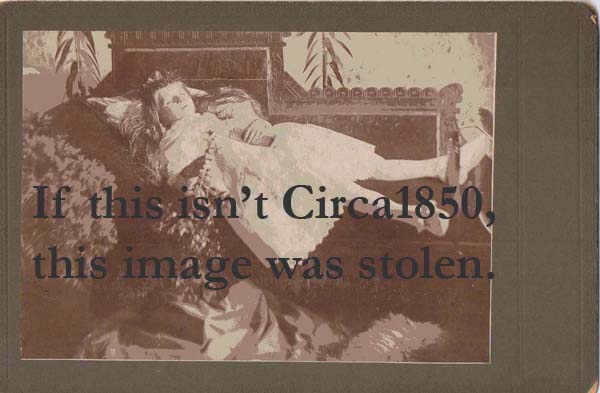

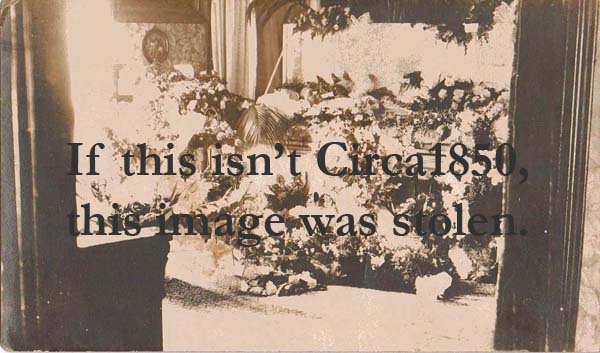

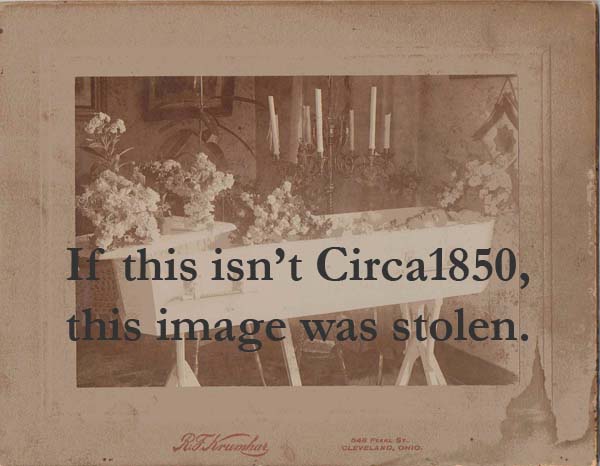

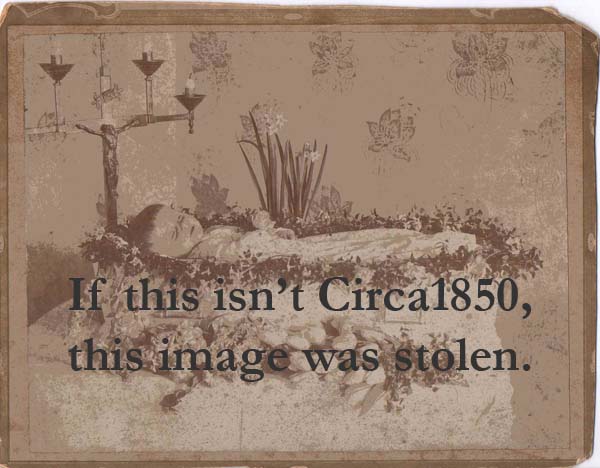

A Wake

October 7th, 2011

Earlier this week, I had reason to rout about in my shelf of photographs. Among the color slides from my husband’s trip to Mexico (circa 1964) and endless albums of wedding pictures, I came across a largish manilla envelope I’d stashed and promptly forgotten. It turned out to be four early 20th century postmortem photographs from my father’s side of the family along with a letter from my Auntie Mary (also my godmother). She sent the packet last year while I was curating Memento Mori: the Birth & Resurrection of Postmortem Photography.

I know that the idea of photographing the dead seems strange today, and even makes some people very uncomfortable. The reactions to the show last year were across the map, but they were all very emotional — which is exactly what a curator wants! A major component of Memento Mori was the amazing collection of The Burns Archive, which celebrated the release of Sleeping Beauty III in conjunction with the exhibition.

In the 19th century, when photography itself was relatively new and fairly expensive, the postmortem photograph was often the only image made of a person, especially in the case of childhood deaths. In their anxiety to have a picture, any picture, to remember their loved one by, bereaved families relied on the miracle of the camera. Photographers charged a premium to transport their cumbersome equipment and dangerous chemicals to the home of the deceased. Sometimes they worked to make the corpse seem as life-like as possible, posing it in a bed, or painting the eyes open once the plate was developed. In other cases, the body was photographed in a coffin, surrounded by candles and flowers. Before photographs, hiring an artist to make a painting or sculpture (or death mask) was the only way to make a portrait. Photography democratized personal memorials.

These are the four postmortem photographs that Auntie Mary sent. They are unidentified, but we know they belonged to our family, and were likely of family members. Postmortem photographs were extremely personal mementos, and are rarely labeled.

You’re probably wondering why I took the trouble to tag these photos with a snarky message. Normally I don’t care who borrows the photos I post (just don’t link back to the copy on my server please) but these seemed a little different. First of all, I know there is a demand for postmortem photographs. People are fascinated by them, and there just aren’t that many available; I know these will attract some attention. They’re also very precious to me. I want to share them with you, but I also want to make sure that people searching for images online think twice about reusing them.

West Indian Monster

August 27th, 2011

As choruses of “Irene, Goodnight” ring out from the more enlightened tenements in Greenwich Village, I can’t help regretting the days when storms were christened in more poetic fashion. We don’t yet know whether Hurricane Irene’s New York landfall — forecast for the wee sma’s of Sunday, August 28, 2011 — will enter the annals of history as a great disaster, but it did get me wondering about New York’s previous hurricane history.

The City’s worst recorded storm took place in early September, 1821. It first made landfall in North Carolina, and roared up through the Delmarva penninsula and New Jersey before slamming into New York City and Long Island. This may sound unnervingly familiar if you have been following the track of our 2011 storm. But 1821 hit much harder than Irene is likely to do. 13 foot surges from both rivers pushed across the City, entirely flooding Manhattan south of Canal Street. Jeepers!

In 1893, a serious hurricane — colorfully dubbed the “West Indian Monster” — again tore across the City and Long Island. It completely demolished, as in, it no longer exists, a small barrier island known as Hog Island (because Native Americans kept pigs there). Here’s what The New York Times had to say about conditions in Brooklyn on August 25, 1893:

“In such a savage manner did this West Indian monster of the air conduct itself that when the gray light of dawn came upon the city its inhabitants looked tremblingly forth upon a widespread scene of damage and destruction.”

Then the City was hit again in 1938, by a storm now known as “The Long Island Express.” In that case, I think I’ll let the pictures speak for themselves.

If I only had a canoe…

In all seriousness, we are well stocked with fresh water, non-perishable food, candles, and a battery powered radio. Our building stands in a zone that will only be evacuated in case of a much more serious storm. All our windows are closely flanked by other buildings — usually a source of frustration because of the miserable light that trickles down into our garret. But in this case, we are glad to be so well protected. At the worst, we may be without power for a day or two — a good excuse to turn off the computer and pay attention to something real. I’ll keep you posted.

Bananarama

August 3rd, 2011

This evening, I ventured forth from our garret in search of ice cream. It seems the type we wanted is no longer made, so I was forced to make a second choice. On a whim, I opted for chocolate covered frozen bananas instead.

An 1891 illustration of banana cultivation.

It wasn’t ice cream, but they were quite tasty and surprisingly refreshing. And they inspired me to look up this 1888 Good Housekeeping article extolling the virtues of this tropical fruit and encouraging housekeepers to introduce them to the family table.

BANANAS.

Of Large Food Value At Low Cost.

The banana has long been known as a tropical fruit in this country and counted among the luxuries of life, yet its more important use, that of a food, has received but little attention in modern times, though it was in common use for this purpose in the early part of the sixteenth century, and in tropical countries it takes the place of our cereals, forming a very important food. Its composition is about the same as the potato, and like that esculent it is an imperfect food by itself, but very valuable in combination with something more nitrogenous, such as lean meat or fish. Prof. Johnston says that in tropical America six and a half pounds of the fruit, or two pounds of the dry meal with a quarter of a pound of salt meat or fish form the daily allowance of a laborer. It is said to yield a larger supply of food than any other known vegetable, from a given amount of land, and according to Humboldt a space that would yield four hundred and sixty-two pounds of potatoes or thirty-eight pounds of wheat would produce four thousand pounds of bananas, which makes it a valuable crop to cultivate. After the tree bears one bunch of fruit it dies down and others spring up around it, but a single bunch weighs sometimes from seventy to eighty pounds, though the average quantity from a tree is but thirty to forty pounds. It is the bread of the tropics, for while unripe the fruit is filled with starch cells. In this state it is dried in the oven, when it tastes very much like bread and will keep a long time. When the fruit ripens the starch changes to sugar and it becomes sweet as we eat it. Some sages have thought the banana and not the apple caused Adam’s fall, poets even perpetuating it through ages, as for example, “Fruit like that Which grew in Paradise, the bait of Eve, Used by the tempter.”

A recent writer has said that “the banana, when ripened in the tropics, possesses the flavors of all other known fruits, and when fully ripe it fills the air with richest scents.” They have become a very important article of commerce, the imports of the banana having in a few years nearly trebled. Some years since a consignment of four thousand bunches was thought a large cargo, but now steamers are constructed to carry this fruit alone, and from eighteen to twenty thousand bunches is an ordinary load. Importing them in such quantities has tended to reduce their price and from selling at fifty cents to one dollar the dozen, they are now within the reach of the smallest purse and can be bought from twelve cents a dozen to twenty-five, the latter price being for large fine ones. As their cost is low, and their food value large, they should often appear on the table in various forms, so that we can increase the variety that gives zest to appetite, and yet makes the change that is so desirable to prevent one from feeling surfeited, from even too much of a good thing. They are good for breakfast or at dessert when they are ripe, in their natural state, or for a change in banana sponge, a salad, jelly, etc.

This post is dedicated to my dear friend K. E. M., aka Banana.

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »