Fashion Victime

May 17th, 2011

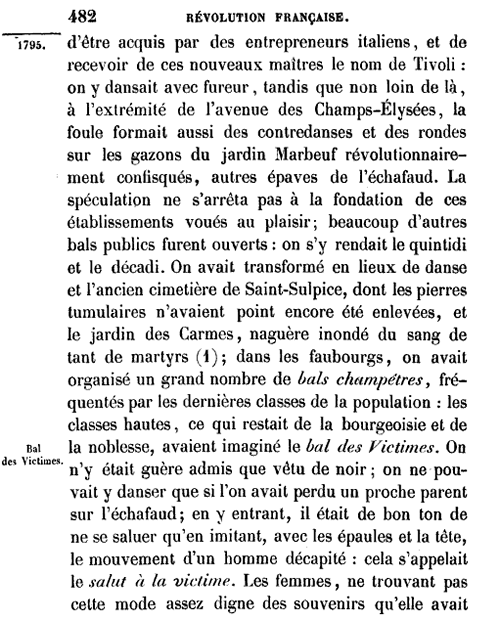

There were a number of books and articles published in the mid to late 19th century describing a phenomenon known as Bals des Victimes, that may or may not have taken place in the days following Robespierre’s death and the reinstatement of the French nobility. Here’s a relatively early one from Histoire de la Révolution et de l’Empire, published in 1847.

Unfortunately, my French, limited to begin with, is quite rusty. I believe the gist of this page is as follows:

At the far end of the Champs-Elysees, the crowd of dancers formed on the lawn of some garden that had been confiscated during the revolution, and there were some others around the old gallows of the guillotine. It didn’t stop at the beginning of the red light district either — there were lots of parties open to the public: for five days. They transformed the ancient cemetery of Saint-Sulpice into a dance floor, etc., etc. … In the outlying areas of the city, a great number of pastoral-themed parties were organized, frequented by the latest [lower??] classes. The upper classes, who had been reinstated to the bourgeoisie and the nobility, came up with the Victim’s ball. These were exclusive — in order to get in you had to have lost a parent to the guillotine. Upon entering, it was fashionable to perform a salutation with your head and shoulders imitating decapitation; this was called the Victim’s Greeting.

It goes on, but I cannot.

Here, from an 1867 book about the Empress Josephine, is a description in English:

This was especially the case at the so-called victim balls (bals a la victime) which were given by the heirs, the sons and fathers of those who had perished by the guillotine. People gathered together in brilliant entertainments and balls to the honor and memory of the executed ones. Every one who could pay the large fee of admission to these bals a la victime were permitted to enter. Those who came there, not for pleasure, but to honor their dead, showed this intention by their clothing, and especially by the arrangement of their hair. To remind them that those who had been led to the guillotine had had their hair cut close, gentlemen now had theirs cut short, and the dressing of the hair a la victime was for gentlemen as much a fashion as the dressing of the hair a la Titus (the Roman emperor) was for the ladies. Besides this, the heirs of the victims wore some token of the departed ones, and ladies and gentlemen were seen in the blood-stained garments which their relatives had worn on their way to the scaffold, and which they had purchased with large sums of money from the executioner, that lord of Paris.

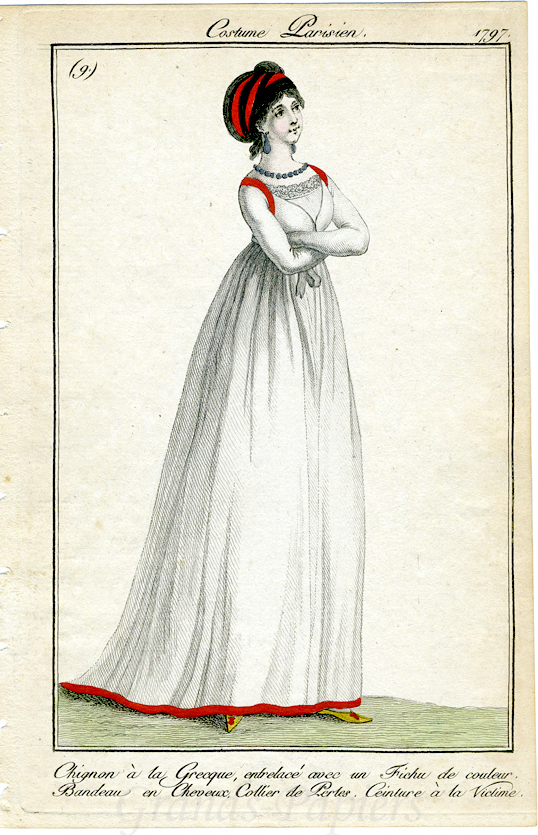

As you may guess, I am particularly interested in the fashions associated with this legendary (historians seems to disagree as to whether these events actually took place or were merely figments of later romantic imaginations) custom. A friend who grew up in Paris told me about men and women who wore red ribbons tied round their necks where the blade would have fallen, and there was a fashion for women to wear close cropped hair in imitation of someone about to be executed. Classically inspired robes, like the dress I am in the midst of making right now, were also popular. Some sources claim that attendees wore mourning clothes, including crape bands about the arm. However I don’t know if that type of mourning dress was even invented as early as the turn of the 19th century, which would mark those accounts at least as pure fabrication.

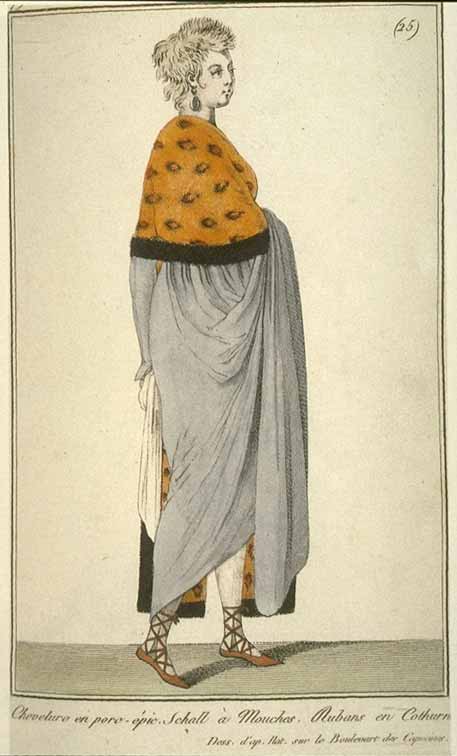

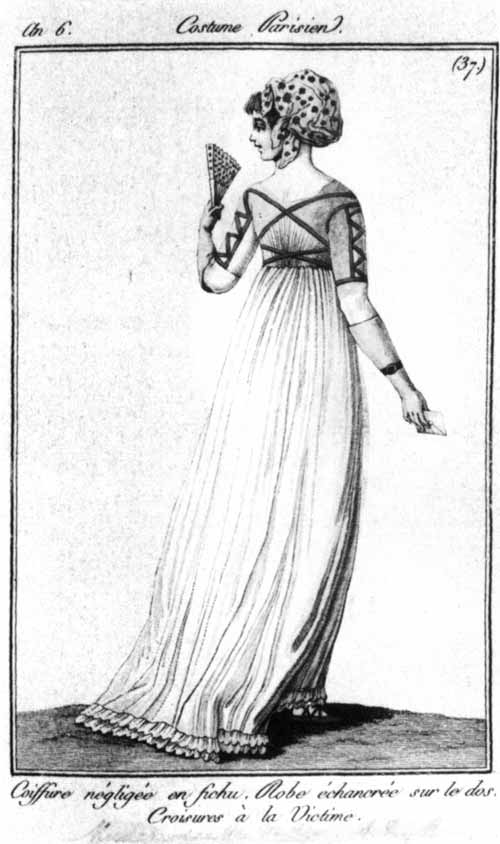

Here are a few fashion plates from late 18th, early 19th century France. Notice how each refers to various styles a la victime?

Very Grecian!

Notice the ribbons bound about her feet — some Victimes wore no shoes, just ribbons tied around their feet and ankles.

The Exhibit is Open

April 14th, 2011

And I do hope you’ll come and see. It’s rather incredible, if I do say so myself (all I did was some writing and fabricating, so it’s no violation of modesty for me to layer on the invective in favor of the amazing collection that is on display). Where else can you gaze at one-of-a-kind Civil War medical portraits, not seen since the 19th century? The photos on display are from The Burns Archive, and include hauntingly beautiful album prints by Civil War Army surgeon R. B. Bontecou, a few by Mathew Brady, and many others. The entire exhibit is captioned with quotes from Walt Whitman’s memoir of Civil War nursing, Specimen Days.

The exhibit tips its hat to Dr. Stanley Burns’s latest book, Shooting Soldiers, which has been released just in time for the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, and features many of the Bonetcou images. There’s also a small annex devoted to New York’s Seventh Regiment National Guard and The Siege of Washington, by John Lockwood and Charles Lockwood, also recently released.

Image courtesy of The Burns Archive

But don’t take it from me. Here’s what our local public radio station, WNYC, had to say.

And here are the details on how you can see these photographs in person — a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that should not be missed by anyone interested in photography, history, or the Civil War:

Exhibit Dates: April 14, through August 1, 2011

Location: Merchant’s House Museum (29 East Fourth Street, NYC)

Title: New York’s Civil War Soldiers

Open: Thursday-Monday (closed Tuesday & Wednesday), noon to 5 p.m.

Price: Included with regular admission, $10, $5 Students & Seniors (a real bargain, as you get to see the rest of the Museum as well)

Bonus: Say you know “Eva” and get a strange look from the person working the door…

Lady Grey?

March 29th, 2011

My great-great grandmother, Agnes Gray (Grey), was Scottish. I’m not sure if she was born in Scotland, or if her parents immigrated to America first. Regardless, my own grandmother has always been interested in our Scottish heritage. She had a suit made in the Sutherland tartan, but I was never quite sure how that connexion worked. How could someone named Gray belong to the Sutherland clan?

Well it turns out that the Grays (Greys) are a sept, or sub-division of the Sutherland clan. The Grays came over to England with William the Conqueror, and later fled up to Scotland after doing something naughty down south. By the 16th century, they were allied with the Sutherlands and installed in Skibo Castle. The Grays intermarried with the Gordons, whose line still holds the ancient (created in the early 13th century) Earldom of Sutherland, and, until recent generations, held the newer (created in the early 19th century) Duchy of Sutherland.

Skibo Castle, which was held by the Grays for more than 200 years, until the 1770s, was rebuilt in the late 18th century. So I couldn’t find a picture of what it might have looked like during the years when “my family” held it. In the early 20th century, the new castle was purchased by American millionaire Andrew Carnegie. The castle is still owned by the Carnegie club, and is run as a posh estate hotel. Madonna was married at Skibo Castle.

Oh how the mighty have fallen.

Which isn’t to say that I am actually related to Scottish nobility. We probably came from the poor-relation branch of the family. But I think it is fair to say that I am descended from the same Gray (Grey) who accompanied the Normal conqueror. Why do I suddenly have even less sympathy for Ivanhoe?

You can read more about the Sutherland clan on their website.

Lecture Report

March 24th, 2011

Last night, I gave a “hands-on” presentation at the museum where I work. It was called Hand-Sewing in the 1850s — 60 Years before the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, presented in collaboration with Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition’s 100th anniversary memorial.

The Song of the Shirt, by Anna Blunden — one of the illustrations I used in my talk.

To my great delight, 35 people turned out for the lecture, despite miserable left-over-winter weather that included rain, snow, sleet, hail, and thunder. Everyone seemed very interested in the topic at hand, and after the slides were finished, the crowd proved their good nature by trying out some of the hand-sewing stitches we’d been discussing. I was particularly pleased to meet so many fellow sewers, including two ladies who work at an historic farm, and a costumer from a local ballet company!

I recorded the talk for some friends who couldn’t be there, and though I haven’t had the courage to listen to it myself, my husband assures me it was quite presentable. I wonder when I’ll have the chance to do it again, and what I shall talk about.

Now back to my stays…

Radio Appearance

March 7th, 2011

A couple of weeks ago, I was interviewed at work by George Bodarky for his Cityscape program on WFUV radio in New York City. The title of the show was The Inevitable, and guests included the obituary writer for the New York Times, a representative of the legendary Greenwood Cemetery, and me. It seems I have become something of an authority on death and funerals in mid-19th century New York.

If you care to listen, here’s a link to the show page.

Why, you ask, do I know so much about death? Mostly, it’s because we host an annual exhibition about death and mourning every October at the Merchant’s House Museum. We also recreate a mid-19th century funeral, complete with corpse (faux), coffin (reproduction), and a tour of the New York City Marble Cemetery. That’s where the talented Stephanie Swinton snapped this photo of me posing with an obelisk.

Photograph by Stephanie Swinton