Memorial Day

May 30th, 2011

The first Decoration Day (the original name of our modern Memorial Day holiday) was held in May of 1868, to commemorate those who gave their lives in service during the Civil War. It was a day for laying flowers and wreaths on the graves and monuments that represent our fallen warriors.

Despite an existing 19th century-precedent, the New York Nineteenth Century Society — of which I am a co-founder — decided to celebrate Memorial Day with a salute to Lord Byron. I can’t explain it, I know it makes no sense, but there it is. So we organized an excursion via railroad to Wave Hill, a botanic garden in Riverdale on the Hudson River. We called our gathering “Hours of Idleness: A Neoclassical Picnic.”

The company was motley and merry, some traveling by train, others by car, none by ferry boat. After a jolly picnic in the appointed area, we strolled about in smaller groups, equipped with some of the shorter poems from Byron’s Hours of Idleness, though I’m not sure how many bothered to read them — the views of the Hudson being all engrossing. When the heat became too much for us, we gathered on a shady lawn to loll about a while. That’s where I painted this atrocious watercolor.

I have lately begun to revolt against the constant use of digital cameras. It’s all too easy to let the documentation of a good time take over the very thing it is trying to record. So I brought my watercolors along instead. Of course, I am still grateful to the photographers — particularly since I would have other way of showing you my completed Empire dress. But that is for another post.

Until then, Happy Memorial Day, and deepest thanks to all who have served our country so bravely over the past century and a half.

Lines, Written Beneath an Elm…

By Lord ByronSpot of my youth! whose hoary branches sigh,

Swept by the breeze that fans thy cloudless sky,

Where now alone, I muse, who oft have trod,

With those I loved, thy soft and verdant sod;

With those, who scatter ‘d far, perchance, deplore

Like me, the happy scenes they knew before;

Oh ! as I trace again thy winding hill,

Mine eyes admire, my heart adores thee still,

Thou droopi ng Elm ! beneath whose boughs I lay,

And frequent mused the twilight hours away;

Where as they once were wont, my limbs recline,

But, ah! without the thoughts which then were mine:

How do thy branches, moaning to the blast,

Invite the bosom to recall the past,

And seem to whisper as they gently swell,

“Take, while thou canst, a lingering, last farewell!”When fate shall chill, at length, this fever’d breast

And calm its cares and passions into rest,

Oft have I thought ‘twould soothe my dying hour,

If aught may soothe, when Life resigns her power;

To know some Humbler grave, some narrow cell,

Would hide my bosom where it loved to dwell,

With this fond dream methinks ‘twere sweet to die,

And here it linger’d, here my heart might lie,

Here.might I sleep where all my hopes arose,

Scene of my youth, and couch of my repose:

For ever stretch’d beneath this mantling shade,

Prest by the turf where once my childhood play’d;

Wrapt by the soil that veils the spot I loved,

Mix’d with the earth o’er which my footsteps moved;

Blest by the tongues that charm’d my youthful ear,

Mourn’d by the few my soul acknowledged here,

Deplored by those, in early days allied,

And unremember’d by the world beside.

To Mother

May 8th, 2011

Mother’s Day, as we know it, was declared a holiday in 1870 by Julia Ward Howe, who grew up not far from where I live and is best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” She originally set the date in June. But odes upon the importance of motherhood are as old as time itself. Here are a couple of gems, complete with illustration, from Godey’s Lady’s Book.

WE do not hear much of the mothers of great men. What their fathers were— what their reputation, qualities, and history— is related to us with great particularity; but their mothers are usually passed over in comparative silence. Yet it is abundantly proved, from experience, that, the mother’ s influence upon the development of the child’s nature and character is vastly greater than that of a father can be. “The mother only,” says Richter, “educates humanly. Man may direct the intellect, but woman cultivates the heart.” — Godey’s Lady’s Book, May 1854

THE MOTHER’S BLESSING

“MY mother ! my first, best friend! As I sit here, looking far back into the past, I can trace in every act that did me credit the influence of her love her tender care; and on every unworthy deed I seem still to see the sad, grieved face, the brimming eye, and, quivering lip she bent over me, trying, by sweet, winning love, to bend my stubborn will; and make me regret the act that caused her so much sorrow. Surely, the best gift in our heavenly Father’s sending is mother’ s love.” — Godey’s Lady’s Book, Mary 1858

Happy Mother’s Day!

Easter Rabbit Stew

April 26th, 2011

I’m not sure when we decided to make a yearly tradition out of stewing the Easter Bunny, but it’s been a few years at least. My husband has a wonderful sense of humor, and we both love the light, slightly fragrant taste of simmered rabbit. This year, I beat the lines at Ottomanelli’s (which later ran down the block) by stopping by early on Saturday morning to purchase my rabbit. For regular use, we buy frozen rabbits in Chinatown for a few dollars. But for the holiday, I like to splurge on a fresh kill.

There’s a long history of eating rabbit, and you’ll find many receipts for rabbit stews, fricassees, etc. As far as I can tell, rabbit was, and is still, a popular dish in France and some parts of Italy. Here, in her 1847 Lady’s Receipt-book, Philadelphia author Eliza Leslie offers directions for French Stew of Rabbits.

That sounds delicious, but I made no attempt to be historical while cooking Easter dinner. At least not technically so. Instead, I tossed together an informal spring stew, based on years of cooking rabbit — the same way many women in the 19th century cooked by instinct and experience. (My mother used to take me to a rabbit farm, where you could pet your dinner before taking it home in a bloody bag.) Here, with illustrations is my “receipt” for rabbit stew.

RABBIT STEW

1 rabbit, whole or cut up

4 small potatoes, diced

2 turnips, peeled and diced

2 parsnips, peeled and diced

4 carrots, peeled and diced

2 stalks celery, diced

2 or 3 onions, chopped

a few cloves of garlic, minced

bay leaf

herbs to taste

1 or 2 cans of crushed tomatoes

Splash of wine

I began by chopping up the vegetables. I put everything EXCEPT the onion and garlic into my crock pot, and tossed them with some rosemary and thyme. I also threw in a large bay leaf.

Then I melted a hunk of butter (about 2 tablespoons) into a pan and sauteed the onions and garlic until they began to caramelize. I added the rabbit, and let it sizzle for a few minutes, turning it so that it would brown nicely on all sides.

Finally, I turned the rabbit, onions, and garlic into the crock pot, scooping some of the diced vegetables to cover them. I poured in a large can of tomatoes, and would have added a nice splash of wine if I’d had an open bottle; I prefer a Bordeaux for rabbit stew. If your tomatoes don’t provide enough liquid (you need at least a few cups) and you don’t use wine, you can also add a little water.

Set your crock pot on low to cook for 6 to 8 hours, or high if you want it to be done sooner, 4 to 6 hours. Of course, you can also cook it over the stove, simmering in a covered pan for about 2 hours. The slower you cook it, the tastier it will be. It also gets better the next day. Reheat over the stove.

Once it’s cooked, you can scoop out the rabbit and flaked the flesh off the bones to be added back into the stew. Or you could be lazy, like me, and just leave the rabbit in tact, pulling off hunks of meat as you serve.

Enjoy!

New Year in Old New York

January 1st, 2011

From Sunshine and Shadow in New York, by Matthew Hale Smith, 1868, slightly annotated by myself:

New York without New Year’s would be like Rome without Christmas. It is peculiarly Dutch, and is about the only institution which has survived the wreck of old New York. Christmas came in with Churchmen, Thanksgiving with the Yankees, but New Year’s came with the first Dutchman that set his foot on the Island of Manhattan. It is a domestic festivity, in which sons and daughters, spiced rums and the old drinks of Holland, blend. The long-stemmed pipe is smoked, and the house is full of tobacco. With the genuine Knickerbockers, New Year’s commences with the going down of the sun on the last day of the year. Families have the frolic to themselves. Gayety, song, story, glee, rule the hours till New Year’s comes in, then the salutations of the season are exchanged, and the families retire to prepare for the callers of the next day. Outsiders, who ” receive ” or “call,” know nothing of the exhilaration and exuberant mirth which marks New Year’s eve among Dutchmen.

THE PREPARATION.

The day is better kept than the Sabbath. The Jews, Germans, and foreigners unite with the natives in this festival. Trade closes, the press is suspended, the doctor and apothecary enjoy the day, — the only day of leisure during the year. It is the day of social atonement. Neglected social duties are performed; acquaintances are kept up; a whole year’s neglect is wiped out by a proper call on New Year’s. All classes and conditions of men have the run of fine dwellings and tables loaded with luxury. Wine flows free as the Croton [the City’s municipal water supply], and costly liquors are to be had for the taking. Elegant ladies, in their most gorgeous and costly attire, welcome all comers, and press the bottle, with their most winning smile, upon the visitor, and urge him to fill himself with the good things. The preparation is a toilsome and an expensive thing. To receive bears heavily on the lady; to do it in first-class style draws heavily on the family purse. A general house-cleaning, turning everything topsy-turvy, begins the operation. New furniture, carpets, curtains, constitute an upper-ten [as in “upper ten thousand,” referring to high society] reception. No lady receives in style in any portion of dress that she has ever worn before, so the establishment is littered with dressmaking from basement to attic. This, with baking, brewing, and roasting, keeps the whole house in a stir.THE TABLE.

Great rivalry exists among people of style about the table —how it shall be set, the plate to cover it, the expense, and many other considerations that make the table the pride and plague of the season. To set well a New Year’s table requires taste, patience, tact, and cash. It must contain ample provision for a hundred men. It must be loaded down with all the luxuries of the season, served up in the most costly and elegant style. Turkey, chickens, and game; cake, fruits, and oysters; lemonade, coffee, and whiskey; brandy, wines, and — more than all, and above all — punch. This mysterious beverage is a New York institution. To make it is a trade that few understand. Men go from house to house, on an engagement, to fill the punch bowl. Lemons, rum, cordials, honey, and mysterious mixtures, from mysterious bottles brought by the compounder, enter into this drink. So delicious is it, that for a man to be drunk on New Year’s day from punch is not considered any disgrace.DRESS OF THE LADIES.

This is the most vexatious and troublesome of all the preparations for New Year’s. Taste and genius exhaust themselves in producing something fit to be worn. The mothers and daughters quarrel. Feathers, low-necked dresses, and gorgeous jewelry the matron takes to herself. The daughters are not to be shown off as country cousins, or sisters of the youthful mother, and intend to take care of their own array. The contest goes on step by step, mingled with tears of spite and sharp repartee till midnight, nor does the trouble then end. Few persons can be trusted to arrange the hair. Some parties keep an artist in the family. Those who do not, depend upon a fashionable hair-dresser, who, on New Year’s, literally has his hands full. Engagements run along for weeks, beginning at the latest hour that full dressing will admit. These engagements run back to midnight on New Year’s eve. Matron or maid must take the artist when he calls. As the peal of bells chimes out the Old Year, the doorbell rings in the hair-dresser. From twelve o’clock midnight till twelve o’clock noon, New Year’s, the lady with the ornamented head-top maintains her upright position, like a sleepy traveler in a railroad car, because lying down under such circumstances is out of the question. The magnificent dresses of the ladies; diamonds owned, or hired for the occasion; the newly furnished house, adorned at great expense; the table loaded with every luxury and elegance; the ladies in their places; the colored servant at the door in his clerical outfit, — show that all things are ready forTHE RECEPTION.

The commonalty begin their calls about ten. The elite do not begin till noon, and wind up at midnight. Men who keep carriages use them, the only day in the year in which many merchants see the inside of their own coaches. Exorbitant prices are charged for hacks [hired carriages]. Fifty dollars a day is a common demand. Corporations send out immense wagons, in which are placed bands of music, and from ten to twenty persons are drawn from place to place to make calls. The express companies [competitors with the early post office] turn out in great style. The city is all alive with men. It is a rare thing to see a woman on the streets on New Year’s day. It is not genteel, sometimes not safe. Elegantly-dressed men, in yellow kids [gloves, that is, of a suitable color and make for daytime wear], are seen hurrying in all directions. They walk singly and in groups. Most every one has a list of calls in his hand. The great boast is to make many calls. From fifty to a hundred and fifty is considered a remarkable feat . Men drive up to the curbstone if they are in coaches, or run up the steps if they are on foot, give the bell a jerk, and walk in. The name of one of the callers may be slightly known. He is attended by half a dozen who are entirely unknown to the ladies, and whom they will probably never see again. A general introduction takes place; the ladies bow and invite to the table. A glass of wine or a mug of punch is poured down in haste, a few pickled oysters — the dish of dishes for New Year’s — are bolted, and then the intellectual entertainment commences. ” Fine day” — ” Beautiful morning” — ” Had many calls?” — ” Oysters first rate” —” Great institution this New Year’s” — “Can’t stay but a moment” — “Fifty calls to make” — “Another glass of punch?” — “Don’t care if I do” — “Good-morning.” And this entertaining conversation is repeated from house to house by those who call, till the doors are closed on business. Standing on Murray Hill, and looking down Fifth Avenue, with its sidewalks crowded with finely-dressed men, its street thronged with the gayest and most sumptuous equipages the city can boast, the whole looks like a carnival.NEW YEAR’S NIGHT.

The drunkenness and debauchery of a New Year’s in this city is a disgrace to the people. As night approaches, callers rush into houses where the lights are brilliant, calling for strong drinks, while their flushed cheeks, swollen tongues, and unsteady gait tell what whiskey and punch have done for them. From dark till midnight the streets are noisy with the shouts of revelers. Gangs of well-dressed but drunken young men fill the air with glees, songs, oaths, and ribaldry. Fair ladies blush as their callers come reeling into the room, too unsteady to walk, and too drunk to be decent. Omnibuses are filled with shouting youngsters, who cannot hand their change to the driver, and old fellows who do not know the street they live in. Joined with the loud laughter, and shout, and song of the night, the discharge of pistols, the snap of crackers, and illuminations from street corners, become general. At midnight the calls end; the doors are closed, the gas turned off, the ladies, wearied and disgusted, lay aside their gewgaws, very thankful that New Year’s comes only once in the season.

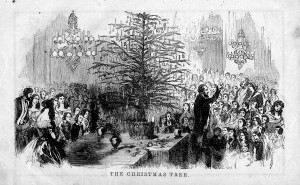

The Christmas Tree

December 24th, 2010

Godey’s Lady’s Book (one of my favorite magazines, in case you hadn’t noticed) was instrumental in popularizing the Christmas tree in America. They (re)published a British illustration of Queen Victoria’s Christmas tree in 1850 — by 1851 the first Christmas trees were being sold in New York City markets. Of course Christmas trees were around before 1850, particularly in the homes of German immigrants. But it took an engraving of the queen and her German-born husband, Prince Albert, around their Christmas tree in Windsor Castle to convince the average American WASP that this charming custom should be universally adopted, whether in the home or in public displays.

The Christmas tree tradition took root (pun intended) quickly. In December 1855, Godey’s published this historical justification of the new custom:

« Newer Posts