Escape from Barsetshire

October 18th, 2011

While recovering from a cold over the weekend, I finally finished The Last Chronicle of Barset. I nearly shouted for joy as I turned the final page. Not that I didn’t enjoy my Trollopian sojourn this year, but really, enough is enough. I am sure I shall eventually tackle the Pallisers, and I even have a copy of The Way We Live Now lurking on my shelf. For now though, I’ve had my fill.

Like Hardy’s Wessex, Barset has become a real county to me. I am conversant with its geography, topography, politics, and social moires. I know which families I’d be likely to get on with, and which invitations I’d do better to decline. I am familiar with everybody’s strengths and failings, and what they like to drink after a big dinner. And you can bet I took lots of notes, culling quotations in support of various topics I’ve been researching. I’d share some with you, but I fear all the good ones are still in the little notebook of “gleanings” that I keep on my night table, waiting to be transcribed.

Map of Barsetshire, courtesy of The Trollope Society.

For me, Trollope is alternately enthralling and deadly dull. The action often proceeds like a radio soap opera, inching along painfully toward an obvious conclusion. But for chapters at a time, he hits a kind of a rhythm and you are borne along most pleasantly on a rush of clever dialogue, intriguing thought, and perfectly believable emotion.

My favorite part of the Chronicles of Barsetshire was the glimpse they offered into clergical doings. I’m fascinated by the minutiae of religious doctrines and requirements in the mid-19th century. The dread of Roman Catholics is amusing, as is the mistrust of Jews, and curiosity about the mysterious “Musulmen” and “Hindoos.” But I particularly love the partisanship within the Church of England (or similar American sects). It seems silly to quibble over such tiny details, but I suppose it was all quite serious to them at the time — particularly as their cherished hope of heavenly reunion with departed loved ones depended on getting it right!

As is my wont, I couldn’t help applying Trollope to the world I see around me in 2011. I began to imagine how he might write about the scandal rocking the Catholic Church in America today — particularly as the news reports last week announced the first bishop to stand trial. It’s wicked I know, but somehow I can’t stop myself from laughing at the seedy priests and ineffectual bishops that Trollope would have written into the story. Alas, even were he alive today, I fear Trollope wouldn’t touch it with the proverbial ten-foot pole. It would be left to sharper pens, a la Dickens or Fielding, though they might not do it so much justice. Now Mark Twain might have a shot. Or perhaps Melville?

De Duve

October 13th, 2011

Illustration from The Ladies Companion, 1853

The Dove,

As an Example of Attachment to Home.The dove let loose in Eastern skies,

Returning fondly home,

Ne’er stoops to earth her wing, nor flies

Where idler warblers roam.But high she shoots, through air and light,

Above all low decay,

Where nothing earthly bounds her flight,

Nor shadow dims her way.So grant me, Lord, from every snare

Of sinful passion free,

Aloft through virtue’s purer air,

To steer my course to thee.

No sin to cloud, no lure to stay

My soul, as home she springs;

Thy sunshine on her joyful way,

Thy freedom on her wings.– General Protestant Episcopal S. S. Union, 1849

Ode to an Onion Tart

October 11th, 2011

THE ONION TART

OF tarts there be a thousand kinds,

So versatile the art,

And, as we all have different minds,

Each has his favorite tart;

But those which most delight the rest

Methinks should suit me not:

The onion tart doth please me best,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!Where but in Deutschland can be found

This boon of which I sing?

Who but a Teuton could compound

This sui generis thing?

None with the German frau can vie

In arts cuisine, I wot,

Whose summum bonum breeds the sigh,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!You slice the fruit upon the dough,

And season to the taste,

Then in an oven (not too slow)

The viand should be placed;

And when’t is done, upon a plate

You serve it piping hot,

Your nostrils and your eyes dilate,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!It sweeps upon the sight and smell

In overwhelming tide,

And then the sense of taste as well

Betimes is gratified:

Three noble senses drowned in bliss!

I prithee tell me, what

Is there beside compares with this?

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!For if the fruit be proper young,

And if the crust be good,

How shall they melt upon the tongue

Into a savory flood!

How seek the Mecca down below,

And linger round that spot,

Entailing weeks and months of woe,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!If Nature gives men appetites

For things that won’t digest,

Why, let them eat whatso delights,

And let her stand the rest;

And though the sin involve the cost

Of Carlsbad, like as not

‘T is better to have loved and lost,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!Beyond the vast, the billowy tide,

Where my compatriots dwell,

All kinds of victuals have I tried,

All kinds of drinks, as well;

But nothing known to Yankee art

Appears to reach the spot

Like this Teutonic onion tart,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!So, though I quaff of Carlsbad’s tide

As full as I can hold,

And for complete reform inside

Plank down my hoard of gold,

Remorse shall not consume my heart,

Nor sorrow vex my lot,

For I have eaten onion tart,

—Ach, Gott! mein lieber Gott!by Eugene Field

Gleaning

September 28th, 2011

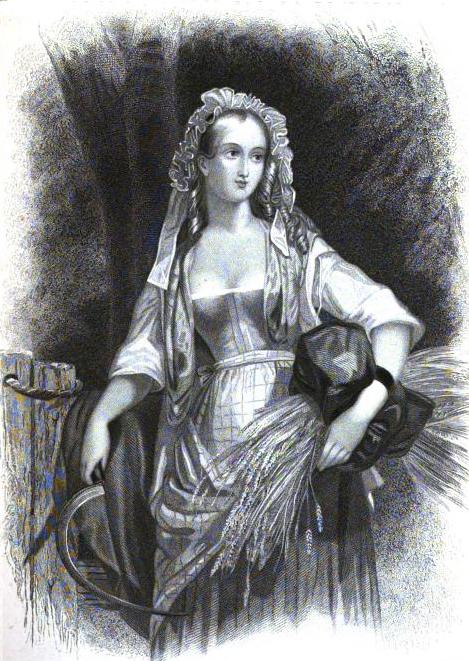

I could have sworn I already posted this illustration and poem, but it doesn’t seem to turn up in any of my site searches. Perhaps it was in the previous version of Circa 1850…before that unfortunate database crash in November 2010? Regardless, here it is again, from The Brilliant, a gift book for 1850, published by T(imothy) S(hay) Arthur, of Arthur’s Lady’s Magazine fame.

THE GLEANER.

Soft, and calm, and very still,

Fell the sunlight on the hill;

When the sultry noontide hour

Gave it most its strengh and power,

Like a glow of soft delight,

On a face with gladness bright;

Telling both of joy and rest,

Gentlest when the happiest.Even thus—as calm as fair,

Resting from the morning’s care,

Leaned, at noon, the dreaming maid,

Where the wood made deepest shade;

Calling back a dear delight,

Whispered to her over night,

‘Neath the boughs whose rustlings seem,

Mingled with her music-dream.May thy dreamings, maiden fair!

Ever such a glory wear—

Ever dwell a smile as meek

On thy yet unshadowed cheek.

Now thy life, like sunshine on,

Even when the dreams are gone;

And when golden youth is past,

Prove the loveliest at the last.

Gleaners were certainly romanticized in the 19th century. Take Tess Durbeyfield for example, who’s apparent innocence is highlighted by her work in the fields even as the presence of her doomed infant belies it. Or Philip Carey who finally takes Sally to his breast after watching her work at harvesting all day. And of course, there is Ruth, the biblical wife par excellence, who remains faithful to her mother-in-law even after she is widowed!

I have a plan to photography myself as a gleaner. Just as soon as I have time to make the costume, probably based on this illustration. I would also love to glean some day. But I have yet to meet anyone with a field of wheat, let alone one in which they would be willing to release me and my scythe.

Words of Wisdom

September 19th, 2011

From Somerset Maugham’s own introduction to Of Human Bondage:

For long after I became a writer by profession I spent much time on learning how to write and subjected myself to a very tiresome training in the endeavour to improve my style. But these efforts I abandoned when my plays began to be produced, and when I started to write again it was with a different aim. I no longer sought a jewelled prose and a rich texture, on unavailing attempts to achieve which I had formerly wasted much labour; I sought on the contrary plainness and simplicity. With so much that I wanted to say within reasonable limits I felt that I could not afford to waste words and I set out now with the notion of using only such as were necessary to make my meaning clear.

I do not know that I have ever taken instructions for writing so much to heart as these few lines. What a clear path they offer — as fine as a razor to walk, but stretching out straight and true, without obstacle or stumbling block — provided of course that one is able to keep one’s balance and not listen too closely to the echoes of those who lost their way and tumbled off the precipice.

Well that was a mouthful. I see myself wobbling already.

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »