Easter Rabbit Stew

April 26th, 2011

I’m not sure when we decided to make a yearly tradition out of stewing the Easter Bunny, but it’s been a few years at least. My husband has a wonderful sense of humor, and we both love the light, slightly fragrant taste of simmered rabbit. This year, I beat the lines at Ottomanelli’s (which later ran down the block) by stopping by early on Saturday morning to purchase my rabbit. For regular use, we buy frozen rabbits in Chinatown for a few dollars. But for the holiday, I like to splurge on a fresh kill.

There’s a long history of eating rabbit, and you’ll find many receipts for rabbit stews, fricassees, etc. As far as I can tell, rabbit was, and is still, a popular dish in France and some parts of Italy. Here, in her 1847 Lady’s Receipt-book, Philadelphia author Eliza Leslie offers directions for French Stew of Rabbits.

That sounds delicious, but I made no attempt to be historical while cooking Easter dinner. At least not technically so. Instead, I tossed together an informal spring stew, based on years of cooking rabbit — the same way many women in the 19th century cooked by instinct and experience. (My mother used to take me to a rabbit farm, where you could pet your dinner before taking it home in a bloody bag.) Here, with illustrations is my “receipt” for rabbit stew.

RABBIT STEW

1 rabbit, whole or cut up

4 small potatoes, diced

2 turnips, peeled and diced

2 parsnips, peeled and diced

4 carrots, peeled and diced

2 stalks celery, diced

2 or 3 onions, chopped

a few cloves of garlic, minced

bay leaf

herbs to taste

1 or 2 cans of crushed tomatoes

Splash of wine

I began by chopping up the vegetables. I put everything EXCEPT the onion and garlic into my crock pot, and tossed them with some rosemary and thyme. I also threw in a large bay leaf.

Then I melted a hunk of butter (about 2 tablespoons) into a pan and sauteed the onions and garlic until they began to caramelize. I added the rabbit, and let it sizzle for a few minutes, turning it so that it would brown nicely on all sides.

Finally, I turned the rabbit, onions, and garlic into the crock pot, scooping some of the diced vegetables to cover them. I poured in a large can of tomatoes, and would have added a nice splash of wine if I’d had an open bottle; I prefer a Bordeaux for rabbit stew. If your tomatoes don’t provide enough liquid (you need at least a few cups) and you don’t use wine, you can also add a little water.

Set your crock pot on low to cook for 6 to 8 hours, or high if you want it to be done sooner, 4 to 6 hours. Of course, you can also cook it over the stove, simmering in a covered pan for about 2 hours. The slower you cook it, the tastier it will be. It also gets better the next day. Reheat over the stove.

Once it’s cooked, you can scoop out the rabbit and flaked the flesh off the bones to be added back into the stew. Or you could be lazy, like me, and just leave the rabbit in tact, pulling off hunks of meat as you serve.

Enjoy!

Life of Spice

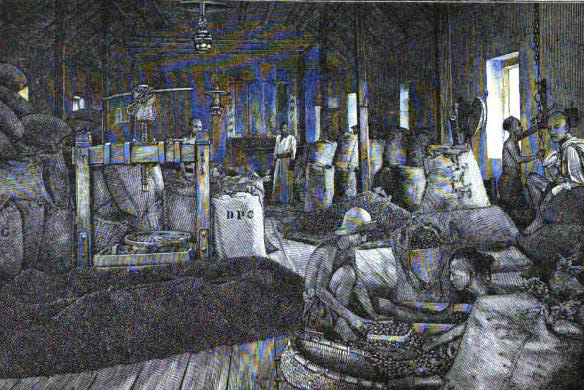

February 28th, 2011

In celebration of my newly acquired spice rack, I present this introductory excerpt from Spices, by Henry Nicholas Ridley, 1912

The history of the cultivation and use of spices is perhaps the most romantic story of any vegetable product. From the earliest known eras of civilisation spices were eagerly sought in all parts of the world. The earliest explorers in their search after gold paid almost as much attention to drugs and spices, and it was the pursuit of these as much as anything which led to the first rounding of the Cape of Good Hope, and the colonisation of the East Indies. Later, the greed of the Dutch in maintaining the monopoly of the Eastern spice-trade led to the founding of the Straits Settlement colony, while the pepper gardens of southern India, the vanilla of Mauritius and the Seychelles, the cinnamon and cardamoms of Ceylon all played important parts in the opening up of these countries to Western civilisation and Western trade.

It must be noticed that the greater part of the spices that have been valued by man are derived from the Asiatic tropics, while the other quarters of the globe have produced comparatively few. Thus we have the following distribution.

From Asia are derived pepper, cardamoms, cinnamon (natives of southern India and Ceylon), nutmegs, and mace; cloves, clove-bark, turmeric, ginger, greater galangal, from the Malay Archipelago; cassia-bark and lesser galangal from China. Africa gave us grains of Paradise, Madagascar Ravensara aromatica, while the American tropics gave us only vanilla, capsicums, and pimento.

The colder climates of northern Europe and Asia produced but few—coriander, cumin, caraway seed, and mustard and calamus root.

Of the East Asiatic tropical spices most are not really known in the wild state, and it is in many cases actually doubtful as to where was their place of origin.

The appreciation of spices as flavouring for the simple rice food of the oriental, extending over unknown ages, has perhaps caused the oriental to cultivate forms of the aromatic trees and shrubs they met with in the forests into the forms we now know them in, but it must be admitted that in most cases the well-known nutmegs, cloves, ginger, and others do not bear any close resemblance botanically to anything we have since met with in the forests. The cause of this disappearance of the original plant may be perhaps due to the removal to or enclosure in gardens of the plant when found in a wild state. In the case of trees of which the fruit is valuable, the native, on finding it in the forest, may form a garden round them, or he may transfer all the seedlings he can find to his garden, or by steadily collecting the crop of seed annually, may practically in time exterminate the plant in the forest, while later selections of the most productive and valuable forms may modify the fruit so much that we can hardly now recognise it.

Spices can be arranged according to the parts of the plant which form the commercial product. Thus in cloves it is the flower bud which is used; in nutmegs, vanilla, capsicums, pepper, it is the fruit; ginger and turmeric the underground stems, cinnamon and cassia the bark. This is perhaps the most convenient way of sorting them, and I have adopted it.

Cultivations in general can be classified into groups in the following way :—

1. Plantation cultivations, which are generally effected on a large scale, and belong to the class of permanent crops, lasting for a number of years. Such are nutmegs, cloves, cardamoms, cinnamon, vanilla.

2. Garden crops, which are done on a smaller scale, are less permanent and often cultivated as a subsidiary crop to other permanent crops. Such are ginger, capsicums, pepper.

3. Field crops, which are done on a large scale as a temporary crop, and often grown in rotation with other field crops. Such are coriander and cumin.

A certain number of commercial spices are hardly cultivated at all, but are derived from wild trees or plants, the demand for them not being greater at present than the forest can supply. Such are Malay cassia-bark and calamus root. Any of them may at any time, however, come into a greater demand, and it would then be necessary to develop the cultivation. It is therefore desirable to pay some attention to them, as it is not always easy to predict their future. Thus calamus root is grown all over the East, as well as in many other parts of the world, in small quantities, as a native medicine, and imported occasionally into European markets. Recently, however, a planter in the Malay states distilled the oil of it, and sent some of it with other oils to Europe for examination. It proved to be in great request by certain brewing firms as a beer flavouring, and was highly valued. The demand for this product was quite unknown to cultivators and distillers in the East.

The produce included under the name of spices comprises all aromatic vegetable products which are used in flavouring food and drinks, but almost all have other uses as well, for which they are in great request in commerce. Many are used in perfumery, or in soapmaking, such as vanilla, cloves, and pepper, others in the manufacture of incense—cinnamon. A good number are utilised in medicine, either as a flavouring, or for their special therapeutic values—cardamoms, ginger, nutmegs, etc. Turmeric is used in dyeing, especially by natives; clove oil in microscopy, and others of the spices in various arts. All these uses add to the commercial demand, and are of considerable importance to the planter.

Of late years there can be no doubt that the use of spice as flavouring by European nations has considerably diminished. In the twelfth and later centuries the use of spice in every household was very large, and was only regulated by their cost. But the last few years have shown a certain amount of falling off in the demand for spiced foods, and the spice-box is not so important a household utensil as it was. Artificial flavourings, too, have made some amount of alteration in the demand. But if profits on spices are not as large as they were in the days when, next to gold, spices were considered most worth risking life and money for, there is still a good profit to be obtained by their cultivation. The trade is still large among European nations, and the demand by orientals, the greatest spice-lovers, is as large as ever it was.

Here it is, my new spice rack.

Secret of the Scone

January 30th, 2011

My Scottish and Irish forebears must look down from Brigadoon and smile as they see me baking scones nearly every week. Oddly enough, the recipe I use was given to me by Auntie Mary, from the Slovenian side of the family.

Auntie Mary is a phenomenal baker of the old school. Her scones are light and fluffy, her pies are rich and flaky, and her quick breads are beyond compare. Here is the original recipe, a closely guarded secret until this moment; I even won a ribbon at the County Fair with a batch of these scones, many years ago.

Auntie Mary’s Scones

Sift Together

2 Cups Flour

2 Tablespoons Sugar

1 Tablespoon Baking Powder

1/2 Teaspoon Salt

1/4 Teaspoon Baking SodaStir In (Optional)

1/2 Cup RaisinsAdd

1/2 Cup Sour Cream

1/3 Cup Milk

1/4 Cup Oil

1 Egg, Slightly BeatenStir ingredients until just blended. Turn out the dough onto a slightly floured board and knead gently, usually just a few strokes are sufficient to perfect the mixing. Form into a flattened circle, about an inch thick. Cut into eighths. Bake on an ungreased tray at 425 degrees for 10-15 minutes, or until lightly browned.

The result is a toothsome teatime treat. Smother them in clotted cream (or whipped cream mixed with a little sour cream if you can’t get your hands on real, fresh clotted cream) and berry jam. Repeat as desired.

The true art of the scone, however, is in the variations, usually invented on the spur of the moment. Here are a few I often use. Try them with my blessing — or better still, come up with your own.

- Leave out the sugar, substitute fruit juice (I like orange) for the milk

- Substitute whole milk yogurt for the sour cream

- Add cinnamon and/or nutmeg to the dry ingredients

- Mix a few Tablespoons of dried coconut or ground flaxseed with the dry ingredients

- Vary your dried fruit — cranberries, blueberries, cherries, or try all three

- Use fresh fruit — drained, crushed pineapple is delicious — but be sure to reduce the other liquids

- Add broken nutmeats

- Brush the tops of the scones with milk or juice and sprinkle with coarse sugar before baking

Don’t forget to make a pot of tea! Or a mango tea latte…

Spiced Apple Tarts

January 9th, 2011

I ran into a rather good deal on McIntosh apples this week, and since they aren’t terribly nice for eating, I decided to bake something. I’m still a bit shy of traditional pies after our recent excesses, so my first thought was for apple dumplings. I hied me to the Feeding America Collection and started hunting down receipts. In the midst of all the apple dumplings, boiled and baked and everything in between, I came across this intriguing item in Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book by Catherine Beecher, c. 1845, for Spiced Apple Tarts:

I began by peeling, coring, and slicing 5 or 6 McIntosh apples, plus 1 Granny Smith for flavor. I then proceeded to stew them in a bit of water plus 1 Tablespoon cognac. When they were nice and soft (only about 10 minutes as my stove was too hot), I put them through a sieve. For all practical purposes, it’s applesauce.

Then I added a squeeze of lemon juice — I’d intended to put in the grated lemon rind but got lazy. I spiced it well with liberal amounts of cinnamon and nutmeg (being out of all my other baking spices and desperately in need of a trip to Chelsea Market) and sweetened it with a few teaspoonfuls of blackstrap molasses.

Miss Beecher recommends using a light crust, so I chose my favorite modern tart crust.

Tart Shells

1/4 lb butter

3 ounces cream cheese

1 cup flourBring butter and cream cheese nearly to room temperature. Cream together until light and fluffy. Stir in flour. Form into ball and refrigerate for 1 hour. Divide into 6 pieces for large sized individual tarts, 12 pieces for muffin-tin sized tarts, or 24 pieces for mini-muffin sized tarts. Spread dough into bottom of tart pans with your fingers. Fill and bake, or for cold fillings, pierce the bottom of each tart with a fork and bake blind for 20 minutes at 350 degrees.

I used a set of 6 tart pans that I’ve been meaning to send back to my dear friend (and chef/confectioner extraordinaire) Marla for some time. She sent them filled with 6 of the most delicious homemade-from-scratch pies all the way from California last fall. Using the tins one more time made me feel as though Marla might just drop in for tea and tarts — and I do wish she could!

I was nervous that the wetness of the filling might prevent the tart dough from crisping properly, but my fears were unfounded. The applesauce cooked down a bit as the tarts baked, taking on a delightful, almost apple-butter-like texture. And the crust was firm, flaky, and nicely browned after 20-25 minutes.

They were delicious. The man I cook for enjoyed his portion very much, though expressed a wish for whipped cream, in which I heartily concur. I’ll probably make some to accompany the remaining tarts. Or we can do like Jack Kerouac and simply empty the cream pitcher over them (a story my almost-beatnik husband — they still know him by sight at Caffe Trieste– is fond of relating whenever I serve him pie).

Waffle Party

December 28th, 2010

As ever, when I end up with leftover yams, I’ve been making waffles. I use a delicious recipe for golden yam waffles from that modern compendium, The Joy of Cooking. This morning I’ve made a double batch (thanks to my new enormous glass mixing bowl). After eating our fill, the remainder are bound for the freezer; there will be enough to sustain our waffle cravings for some time!

Waffles are not only tasty however — they are a New York tradition, going back to the Dutch founders, and pleasantly continued throughout the 19th century in the quaint form of ‘waffle parties.’ Read on…

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »