My Favorite Marlowe

April 29th, 2013

Lots of actors have taken on Raymond Chandler’s quintessential private eye Philip Marlowe, including Humphrey Bogart, Robert Montgomery, Dick Powell, Robert Mitchum, and James Garner. But by far my favorite Marlowe is the one you’ve never seen on the screen.

That’s right, Gerald Mohr played the wise-cracking gumshoe in a 3-year-long radio series based on the novels, with script help from Chandler himself. I’m not sure why Mohr never played Marlowe on film, but he sure nailed the character on radio. He also did a stint as Archie on Nero Wolfe — he’s my favorite in that role too.

One of the great things about a character like Philip Marlowe is that he’s become so integrated into the culture he’s taken on a life of his own, separate from creator Raymond Chandler. Springing from the pages of a detective-story magazine in 1939, Marlowe went on to shoot and drink his way through a series of novels, films, and radio plays in the 1940s through 70s, not to mention a fair number of modern tributes in every imaginable medium, including a video game.

If I had to live my life as a fictional man in 1940s Los Angeles, I’d definitely want to be Marlowe.

Little Yellow Bird

April 25th, 2013

My incorrigible husband recently fulfilled his long-time aspiration to acquire a canary. And this isn’t just any bird. He’s a real dynamo — a professional singer with pipes and ego to match. We picked him out because he was beating up all the other birds in the aviary at the pet shop. Aggression seems to be an indication of talent in birds…

Girl with Canary, by Seymour Joseph Guy

Canaries are also a very 19th-century pet. Many ladies kept them to brighten the parlor, housing them in elaborate and decorative cages. Household manuals of the time often included articles on caring for your bird. And here is an excerpt from the introduction to Canary Birds: A Manual of Useful and Practical Information for Bird Keepers, 1869:

A great many people think that to confine birds is cruel. If it were so, indeed, few would be the cage birds one would wish to see; but happily, on the contrary, for those who, like myself, are fond of the little songsters, the more we know about them, the more we are satisfied that theirs is a happy prison. Not for all birds by any means; some would break their hearts, if confined in a cage. The birds of passage, all those that come and go, should never be kept from the sunny skies they seek as winter comes. But with the Canary, as well as a variety of other birds, reared in cages and knowing nothing of that freedom upon which depends almost the existence of their wilder brethren, it would be cruel to expose them to the misery of being loose, little, shivering, trembling strangers, in an unkindly crowd. Poor little creatures, if one of them does get out, how fast it flies to seek some friendly cage; it knows not the language, the ways, and fashions of the birds around it, nor yet does it always meet with the kindest welcome from them. Besides, our canaries want petting—they have no wish, so their gay song tells us, to seek a dirty puddle instead of a crystal bath; to hide from the rain and cower from the cold, instead of hanging singing in a warm pleasant room. Most people forget to reckon on the birds’ social habits; nor do they give them credit for half their loving ways. Canaries are often wild and show fear whenever approached by those who have never shown them kindness. This arises from a natural, and a very proper suspicion, of mankind. Their instinct tells them that the human race are inherently savage; and till they have some convincing proof to the contrary, they never change this, their very correct opinion. To be teased, frightened, slighted, or neglected, is their too frequent fate. But we may add with a deep feeling of pleasure, there are ” exceptions” to all rules, and we know that there are many, many gentle hearts who do love” their birds—aye, and hold converse with them too.

The new little bird has already learned to eat his morning greens from our fingers, and when we aren’t in the room he peeps desperately to hear our answering call. Most of all, he just loves to sing. My husband, a professional musician and radio DJ, exposes him to every style and genre of music imaginable. So far, the canary likes Scriabin, Elvis, Jim Morrison, and the Andrews Sisters, to name a very few. He’s also passionately fond of Linda Ronstadt, or pretty much any high female voice. I’ve even gotten him to sing along with me a few times.

Historian Mary Knapp, my erstwhile mentor and dear friend, introduced me to this poem by Walt Whitman, which sums up our feelings about the bird quite nicely:

My Canary Bird

Did we count great, O soul, to penetrate the themes of mighty books,

Absorbing deep and full from thoughts, plays, speculations?

But now from thee to me, caged bird, to feel thy joyous warble,

Filling the air, the lonesome room, the long forenoon,

Is it not just as great, O soul?

Adventures in Upholstery: Figuring Out French Polish

April 24th, 2013

Thanks to a comment from the incomparable Nick Nicholson, of Nicholson Art Advisory, I’m now pretty sure that my furniture suite is French Polished birch. The good news is I know how to restore the wood finish. The bad news is that I have to French Polish it.

I mentioned this to one of my bridge partners, who owned an antiques and fine art dealership in Berlin, and she related tales of endless buffing, fixing spots on French Polished pieces. Imagine how my shoulder will feel after an entire suite of furniture…

Still undaunted, I ran a quick search of the internet and came up with Project Gutenberg’s French Polishing and Enamelling, by Richard Bitmead, published in London sometime in the late-19th century. Bitmead also wrote guides to upholstery and cabinet-making. I should probably see if I can’t find his work on upholstery…when the time comes for that step of course.

From Bitmead’s preface, describing the invention of French Polish finishing:

Early in the present [19th] century the method generally adopted for polishing furniture was by rubbing with beeswax and turpentine or with linseed-oil. That process, however, was never considered to be very satisfactory, which fact probably led to experiments being made for the discovery of an improvement. The first intimation of success in this direction appeared in the Mechanic’s Magazine of November 22, 1823, and ran as follows: “The Parisians have now introduced an entirely new mode of polishing, which is called plaque, and is to wood precisely what plating is to metal. The wood by some process is made to resemble marble, and has all the beauty of that article with much of its solidity. It is even asserted by persons who have made trial of the new mode that water may be spilled upon it without staining it.” Such was the announcement of an invention which was destined ultimately to become a new industry.

His book also contains sections on dyes, staining, and imitating more costly woods; other types of wood finishes; and even a chapter entitled “Cheap Work,” for those occasions “when economy of time is a consideration.” Hmm, sounds rather tempting.

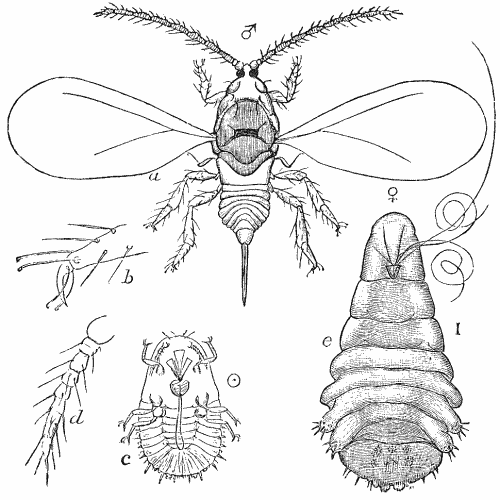

Shellac, the principle ingredient in French Polish, turns out to be an excretion of the female Lac Bug. Once you get over the ick factor, it’s actually pretty cool. Here’s a blog post I found, detailing the Lac Bug and its many uses.

Bitmead’s treatise covers all the steps required to finish raw wood. Since my wood has already been finished, I will either need to sand it down (not sure how I feel about that, both in terms of effort and ethics) or modify the process a little to account for the previous finish layers. Something tells me I’ll be doing a lot of testing on the back legs…

Shall I wrap that up for you?

April 19th, 2013

I’m just barely old enough to remember shopping in a real department store — with a clerk behind each counter, ready and eager to display their wares for your selection. Yeah, I know Macy’s, Saks, and Bloomingdale’s still have counters in some parts of their stores, but it’s not like the old days. To whit, Auntie Mame and the roller skates, or Mary Livingstone at the May Company. That magical moment when you say “I’ll take it — please wrap it up and have it sent to my hotel.”

While shifting my yarn stash into its new tower earlier this week, I emptied out these boxes, relics of the department store days.

This hat box from J. C. Penneys is older than I am. It probably came from my grandmother’s house. Based on the font, I’d say it’s 1970s.

This one goes back to my childhood — I can still remember buying Christmas presents (leather gloves and a wallet for my father) at the Newark Department Store in the little (then) college town where I grew up. Merchandise wasn’t just laying around to sift through, you had to go up to each glass display counter and point to what you wanted, or wait for the clerk to show you a hidden bargain. Clothing was on racks in the center of the store. Downstairs there were housewares, a bargain basement section, and a counter with clothing and supplies for girl and boy scouting.

After a shopping trip, it was next door to Woolworth’s for grilled cheese at the counter. Then we’d look at the parakeets in their little compartments, waiting to be taken home. Sigh.

Gee, I’m not usually so maudlin. Must be spring fever setting in.

More Old Lace

April 18th, 2013

I mentioned a few days ago that I’d been knitting lace patterns from the 1880’s onto the bottom of a modern pencil skirt design. Here’s another.

This pattern is also from Weldon’s Practical Knitter — it’s the border for a “Corinthian Shawl” knitted in reverse. I really like the three-dimensional scale effect of the pattern’s alternating repeats. It’s hard to see in the picture, thanks to poor lighting and dark yarn.

Actually, that overlapping scale pattern is probably the reason it’s called Corinthian. Here’s an illustration of a Greek column, Corinthian order. It’s originally from The Universal Self Instructor, 1883. I’m borrowing it from Clip Art Etc.

The Corinthian also happens to be Georgette Heyer’s first Regency romance novel. In that genre of early 20th-century literature, Corinthian referred to a most eligible bachelor, with a stolid demeanor, an admirable physique, sympathetic eyes, a healthy sum of inherited money invested in The Funds, and calves that looked just as well out of their Hessians. I’m not sure how much the term was actually used in England during the Regency…

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »