Drawers Won

December 27th, 2010

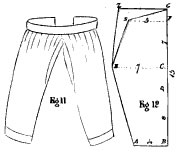

I am now officially halfway done with my embroidered petticoat frill, and felt I deserved a little time off. So I opted to cut out a new pair of drawers. Even though it’s from 1838, I used the Workwoman’s Guide pattern.

The measurements given in the text are for a “moderate” size, which just happens to have a 25″ waistband! Of course that doesn’t include room for overlapping to button or tie, so they’re probably more like a 24″ waist, but that’s an easy enough adjustment. Even though I am rather tall by mid-19th century standards (average height was about 5 feet 2 inches while I measure in at slightly more than 5 feet 7 inches), I didn’t add any length in the crotch, yet they are still sufficiently roomy. I did include an extra inch in the leg — had I been aiming for a true 1838 pair of drawers, I might have added more to the leg, but my understanding of drawers is that they gradually got shorter and puffier as the century wore on (and as cage crinolines introduced the possibility that your skirt might fly up and reveal a peek of stockinged leg — or, heaven forbid, the edge of your drawers).

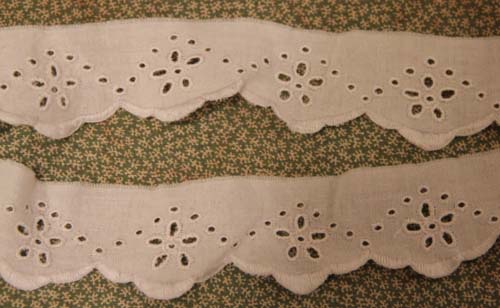

Here’s one of my two legs. I opted for the curved leg (also shown in the Workwoman’s Guide) rather than the straight slope as I plan to put a few tucks at the bottom of each leg. Then, for further decoration, I’m going to attach these frills, pictured below, featuring my very first attempt at Broderie Anglaise.

According to Godey’s in November, 1859:

“Two favorite styles of trimming the pantalettes; the first gathered into a band or cambric embroidery, which is edged by a frill. The second has a hem, straight band of inserting, and frill. They may be also tucked in groups, or simply embroidered on the edge.”

This will be the third pair of drawers that I have made. The first was from Sandra Altman’s excellent Past Patterns and I decorated them with a scalloped eyelet edge directly on the legs, according to the pattern directions. The second pair was an exact copy of a pair in the collection of the museum where I work — Zoh, fashion designer and textile expert extraordinaire made a paper pattern by measuring the original. Then I took over and matched the measurements to various period pattern charts (they lined up perfectly). After that, I cut them out and sewed them up by hand, including a scalloped frill.

Unfortunately, they were meant to be worn by a shorter woman than myself — the leg bands fall right at the widest part of my calf and refuse to button. If I were a few inches smaller, they’d fall below the calf and fasten just perfectly. I plan to use them for a conversation piece. You have coffee table books, I have split leg drawers. Someday, Zoh and I may publish our pattern as a benefit for the museum (that being the original idea of the project).

Hmmmm. I wonder if I should have made these new drawers a little longer after all — though with a few more inches, they’d definitely be in danger of showing ‘neath a swaying crinoline. According to The Handbook of the Toilet, 1841:

“The drawers may be made of flannel, calico or cotton and should reach as far down the leg as possible without their being seen.”

But here’s a quote, a decade later, firmly on the side of shorter drawers, this time it’s from Elements of Health and Principles of Female Hygiene, 1852

“Unless the constitution, however, be peculiarly weak, we should not recommend the drawers to be made of flannel, but of fine calico, and they need not descend much below the knees.”

Oh well. Since they won’t be seen regardless, I suppose it doesn’t really matter one way or t’other! I won’t even go into the question of “to tuck, or not to tuck.”

Once again, another fascinating read. Let’s hear more about this project you and Zoh are doing for the museum.

Nothing to tell at the moment unfortunately — we’re much more likely to launch a series of hand-sewing workshops in the next few months under the auspices of the Nineteenth Century Society…more on that soon!