Mourning, Again?

August 19th, 2011

Gosh, it seems like I am forever pretending that I lived in the mid-19th century and one of my relatives just died.

I was at it again yesterday, as we all pitched in to help artist Hal Hirshorn stage the first of three photo shoots in preparation for an upcoming show that I’m curating. This digital snapshot was taken by one of the other models (there were 7 in total, plus a fake corpse and a coffin).

Someday, I’ll make a more cheerful outfit. I’ve often thought of copying this 1846 painting by Charles Cromwell Ingham:

“Buy a flower off a poor girl?” (Yes, I know, wrong era, wrong country.)

Photographic Shenanagins

August 8th, 2011

As I prepare to curate a new exhibit at the Museum where I work — I’ll share details as soon as they are public — I have been doing a lot of reading about the more unusual types of 19th-century photography. Here are a couple gems that I can’t resist sharing.

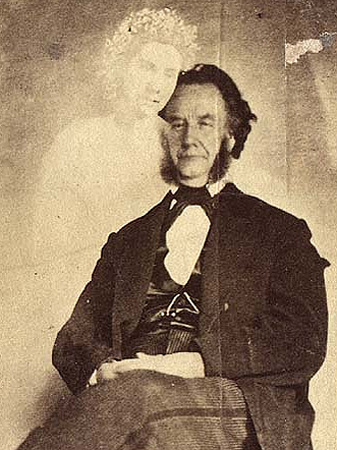

A 19th-century spirit photograph by Wm. H. Mumler

From The Veil Lifted: Modern Developments of Spirit Photography by John Traill Taylor, the editor of the British Journal of Photography, published in 1911:

A mischievous young lady of scientific proclivities who attended the meeting of the British Association, and who was addicted to practical joking, listened attentively to Dr. Gladstone’s observations upon the properties of quinine referred to, and having carefully noted the discission that followed, reasoned within herself thus: If solution of quinine can make invisible marks upon paper, which will come out black in a photograph, it ought to do the same when applied to the skin. So she procured some of this solution, and upon her fair brow she painted with it a death’s head and cross-bones. These, of course, were invisible to human vision. Thus prepared, she went to a photographer to have her portrait taken. All went right until the operator went to develop the plate, when she soon heard an altercation between the photographer and the attendant boy, in which it was evident that the latter was being charged with having coated an old or dirty plate.

A second negative was taken, with this result, that the operator, after bestowing a puzzled, affrighted look at the lady, rushed downstairs to the principal of the establishment. Both returned to the dark room, and a third negative was taken, when it became evident that intense excitement was being produced in the dark room. After an excuse to the lady about there being electricity in the atmosphere, which had affected the chemicals, she was requested to sit once more.

Scarcely had the plate been developed, when both photographer and assistant rushed out from the dark room, pale and excited, and explained that on the brow of the sitter in each negative was emblazoned the insignia of the King of Terrors. The negatives were produced, leaving no doubt of the fact. What was to be done?

The sitter hinted something about not being disposed to be made a fool of by one who she was satisfied was a spirit photographer, and that she, for one, would not allow herself to become the victim of such absurdity. This upset the equanimity of the photographer, who expressed his earnest conviction that she was an emissary and personal friend of the common enemy of mankind.

“I shall look in again to-morrow,” said the lady, in her sweetest tones, “if you promise not to play any of your silly ghost tricks upon me.”

“Not for ten thousand worlds,” said the artist, ” shall you ever set foot within my studioagain!”

“Oh,” she laughingly rejoined, ” I shall drop in through the roof and visit you some day when you are disengaged;” and with that she departed.

“I knew it!” gasped the photographer. “I felt a sulphurous odour the moment I came near her. Send immediately for my friend, the Rev. , and get him to offer prayer, and free the studio from the evil influences remaining after a visitation from one whose feet, although clad in boots, would, if examined, be found to be cloven.”

Ah, for the days when people took the time to play truly original practical jokes. This second item is also hilarious, but perhaps was not intended to be so in its own time. It’s the sheer extravagance of the proposition that makes it so absurd today. Please take particular note of the concluding paragraph.

From Photographic amusements, including a description of a number of novel effects obtainable with the camera, by Walter E. Woodbury, 1922:

PHOTOGRAPHS IN ANY COLOR.

These can be produced by what is known as the powder or dusting-on process. The principle of the process is this: an organic, tacky substance is sensitized with potassium bichromate, and exposed under a reversed positive to the action of light. All the parts acted upon become hard, the stickiness disappearing according to the strength of the light action, while those parts protected by the darker parts of the positive retain their adhesiveness. If a colored powder be dusted over, it will be understood that it will adhere to the sticky parts only, forming a complete reproduction of the positive printed form. Prepare—Dextrine, one-half ounce ; grape sugar, one half ounce ; bichromate of potash, one half ounce ; water, one half pint : or saturated solution bichromate of ammonia, 5 drachms ; honey, 3 drachms ; albumen, 3 drachms ; distilled water, 20 to 30 drachms.

Filter, and coat clean glass plates with this solution, and dry with a gentle heat over a spirit lamp. While still warm the plate is exposed under a positive transparency for from two to five minutes in sunlight, or from ten to twenty minutes in diffused light. On removing from the printing frame, the plate is laid for a few minutes in the dark in a damp place to absorb a little moisture. The next process is the dusting on. For a black image Siberian graphite is used, spread over with a soft flat brush. Any colored powder can be used, giving images in different colors. When fully developed the excess of powder is dusted off and the film coated with collodion. It is then well washed to remove the bichromate salt. The film can, if desired, be detached and transferred to ivory, wood, or any other support.

If a black support be used, a ferrotype plate on Japanned wood, for instance, pictures can be made from a negative, but in this case a light colored powder must be used. The Japanese have lately succeeded in making some very beautiful pictures in this manner. Wood is coated over with that black enamel for which they are so famous, and pictures made upon it in this manner. They use a gold or silver powder.

With this process an almost endless variety of effects can be obtained. For instance, luminous powder can be employed and an image produced which is visible in the dark.

Some time ago we suggested a plan of making what might be termed “post-mortem” photographs of cremated friends and relations. A plate is prepared from a negative of the dead person in the manner described, and the ashes dusted over. They will adhere to the parts unexposed to light, and a portrait is obtained composed entirely of the person it represents, or rather what is left of him. The idea is not particularly a brilliant one, nor do we desire to claim any credit for it, but we give it here for the benefit of those morbid individuals who delight in sensationalism, and who purchase and treasure up pieces of the rope used by the hangman.

I admit I am fascinated by early photographic processes. I fear I may soon be setting up my own darkroom, though am strongly resisting the acquisition of yet another hobby — particularly such an expensive one. For now, I am content to admire the work of others, like the handful of very fine photographic artists who will be included in my new exhibit.

The Exhibit is Open

April 14th, 2011

And I do hope you’ll come and see. It’s rather incredible, if I do say so myself (all I did was some writing and fabricating, so it’s no violation of modesty for me to layer on the invective in favor of the amazing collection that is on display). Where else can you gaze at one-of-a-kind Civil War medical portraits, not seen since the 19th century? The photos on display are from The Burns Archive, and include hauntingly beautiful album prints by Civil War Army surgeon R. B. Bontecou, a few by Mathew Brady, and many others. The entire exhibit is captioned with quotes from Walt Whitman’s memoir of Civil War nursing, Specimen Days.

The exhibit tips its hat to Dr. Stanley Burns’s latest book, Shooting Soldiers, which has been released just in time for the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, and features many of the Bonetcou images. There’s also a small annex devoted to New York’s Seventh Regiment National Guard and The Siege of Washington, by John Lockwood and Charles Lockwood, also recently released.

Image courtesy of The Burns Archive

But don’t take it from me. Here’s what our local public radio station, WNYC, had to say.

And here are the details on how you can see these photographs in person — a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that should not be missed by anyone interested in photography, history, or the Civil War:

Exhibit Dates: April 14, through August 1, 2011

Location: Merchant’s House Museum (29 East Fourth Street, NYC)

Title: New York’s Civil War Soldiers

Open: Thursday-Monday (closed Tuesday & Wednesday), noon to 5 p.m.

Price: Included with regular admission, $10, $5 Students & Seniors (a real bargain, as you get to see the rest of the Museum as well)

Bonus: Say you know “Eva” and get a strange look from the person working the door…

Stand in the Light

April 3rd, 2011

A cause worthy of your notice — and hopefully your support!

“If it were not for the intellectual snobs who pay in solid cash, the arts would perish with their starving practitioners.” – Aldous Huxley

Help prove Mr. Huxley wrong (not that the artist in this particular instance is starving…but you know what I mean). Or am I simply encouraging you to be snobbish? Take it either way.

Photographer & Soldier

February 20th, 2011

Did you know that famed photographer Mathew Brady was an honorary member of New York’s Seventh Regiment National Guard? I didn’t, until last Friday, when I was leafing through my newly arrived copy of The Regiment that Saved the Capital.

Brady had an elegantly appointed studio at Broadway and 8th Street, just around the corner from Cooper Union (where Lincoln gave his famous “Right Makes Might” speech literally hours after Brady took the portrait that helped win the 1860 election). And Cooper Union was just across the street from the new Seventh Regiment Armory*, erected in the late 1850s and home to the Regiment from 1860 to 1880.

The Seventh Regiment was organized in 1806 as a unit of the Volunteer Militia. Also known as the Silk Stocking Regiment, it was populated by scions of the City’s leading families. New York’s Seventh Regiment was the darling of the City, and the nation. Although they didn’t see any real action during the Civil War, their gallant march to reinforce the Capital in April 1861 (just at the beginning of the war) is credited with inspiring much of the bravery and sacrifice that followed.

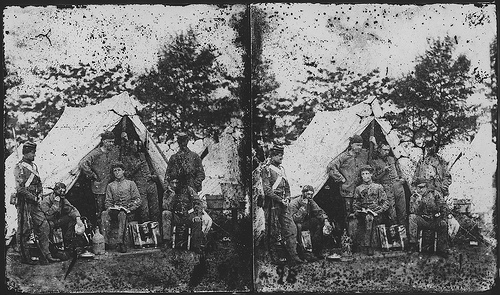

From the United States National Archive

No wonder that Brady, one of the most famous photographers then and still (thanks in part to his work during the Civil War), was sought by the elite Seventh Regiment. And no wonder that Brady was ready to ally himself with the North’s star regiment. Needless to say, Brady took a number of photographs of his fellow guardsmen, including this stereoscopic view of the men lounging outside their tent. I only wish I had a stereopticon plug-in for my blog.

*Interesting note about the 7th Regiment Armory building — the Regiment only occupied the higher floors. The ground floor belonged to the Tompkins farmers market! What an interesting juxtaposition that must have been.