It’s Getting to Be Guipure

September 25th, 2011

I got stranded somewhere this week for a few hours, and just happened to have my crochet bag with me. So I made better progress than expected on row 5. Now I’m on to row 6 — of 8 — and it’s really starting to look like a cohesive pattern. The last two rows are much less involved too, so it’s fair to say I am nearing the finish line on this latest edging. Of course that means I need to start thinking about the petticoat it will eventually adorn…

Row 5 Begun

September 21st, 2011

My latest petticoat trim continues to progress in an orderly fashion. This one isn’t nearly so quick to work up as the last, and by rights it should be taking even longer — I just realized that the pattern asks for size 16 thread, not size 10 like the first (crochet thread gets thinner as the numbers go higher).

Tonight, while watching reruns of Bonanza on DVD — come on, who doesn’t love Little Joe? — I finished the last four motifs and started on the first of three or four more rows that will join it all together.

If you will recall, this is the pattern from Peterson’s, 1855, that’s meant to imitate guipure — a type of embroidered thread and cut fabric lace also popular at the time, and somewhat interchangeable with crochet. I’m not sure how I feel about it, after reading the following in Miss Lambert’s 1848 treatise, My Crochet Sampler:

“The following six collars, though simple and unpretending, are in better taste and style than most productions of a similar kind, in crochet: they show themselves to be what they really are — a clever and ingenious method of producing an elegant and useful article of dress, without attempting to imitate, (which indeed would be but waste of time), lace, guipure, or any other manufacture. This description of work, if well executed, may rest on its own merits.”

Of course I plan to make all of the “following six collars” in the very near future. Though I think I will need to order some finer cotton and dig out my REALLY tiny hooks (or tambours as they were properly called in English, before the french term crochet, meaning hook, took over in the 1840s — I’ve also seen them referred to as crochet needles). I’ve been doing a lot of reading about the development of crochet in the first half of the 19th century, including other works by needlework greats Miss Lambert, Cornelia Mee, and Eléonore Riego de la Branchardière, to name a few. I’ve also found at least four new petticoat trims in crochet from the 1840s and 50s, including one worked the short way!

For now, back to my faux guipure.

Crochet Edging

January 17th, 2011

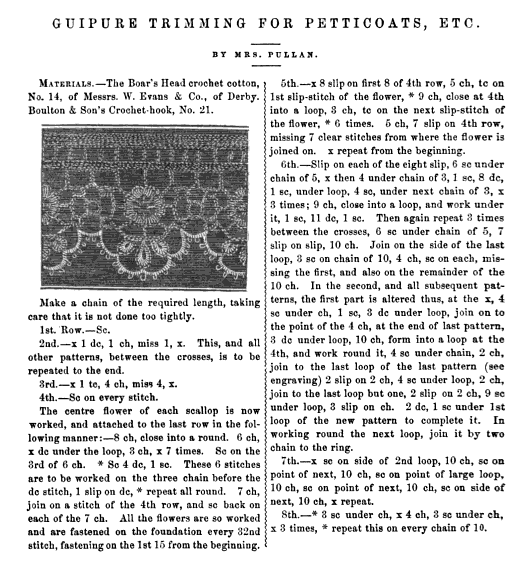

Here’s another edging, recommended for petticoats, from Peterson’s, 1855.

The pattern was remarkably well written and easy to follow, especially with the clear and accurate illustration. I still haven’t figured out how to gauge sizes on 19th-century cotton, but I’ve found some patterns for very fine tatted lace that call for no. 20 or 30 boar’s-head cotton, and directions for a coverlet calling for no. 10. So I am going to presume that, like today, the higher size numbers indicate finer thread. This pattern bears that out as well, asking no. 10 for a petticoat trim, but 16 or 20 for a child’s drawers.

I used what I had on hand to make up a sample — modern no. 16 cotton and a 1.3 mm hook. I don’t think I’d want to trim a petticoat with anything thicker than a modern no. 16; this is a pretty edging, but a bit on the stiff side already. It does seem strong, which was a frequently stated prerequisite for any undergarment trimming (they boiled their laundry, then it was wrung out, and finally put it through a mangle).

Best of all, even though it is worked over the full required length for the first four rows, it does work up relatively quickly. I wouldn’t mind making 100 or so inches of this to trim a petticoat. Someday.

Guipure Trimming

January 11th, 2011

Some women indulge themselves with expensive perfumes, dark chocolate, or spa visits. I subscribe to Accessible Archives. For a modest yearly fee, I can search every issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book ever published, not to mention lots of other great historical sources. The only down side is that since I find whatever I want immediately, I rarely bother to browse. And browsing is the best way to come across what you aren’t looking for.

Peterson’s Magazine, a Godey’s copycat, is searchable only through a very expensive academic database. So I read back issues, bound by the year, thanks to Google Books. I was browsing Peterson’s 1855 for chemise patterns when this showed up:

Given my recent obsession with petticoat trimming, I earmarked it for a trial run. And last week, I pulled out my crochet hook and a skein of cotton thread and whipped up 4 repeats of the pattern. Since the way thread and needle sizes are designated have changed since the 1850s, it’s always a bit of a guessing game to see which you should use. I had number 16 cotton on hand, and a size 10 (1.3 mm) crochet hook. The hook was a little small for the thread, but the next one up in my kit was far too big.

I really like the way this pattern looks. Though I would prefer a finer thread. Probably a great deal finer. Like most crochet edgings, it starts with a chain as long as you will require. There are only 7 rows, but at least two are quite involved. I think it would be slow going to trim a full petticoat, though not nearly so slow as Broderie Anglaise. And the effect would likely be stunning.

I had to fiddle with the pattern a little to make it work; thank heavens for the picture, which helped with intuitive leaps when the written directions became unclear. Some of the changes I made might not have been necessary though if I’d been using finer thread…and the end result would likely have been neater.

Oh, and if you are afflicted with curiosity, like me and the cat, real guipure is a heavy needlepoint lace in which the patterns are connected by thread ties or mesh. True lace, which was phenomenally expensive in the mid-19th century, was often imitated by crochet. One of the most noted examples of this is the legendary Irish crochet: “faux” laces created with great dexterity and sold by women to support their families during the Famine. Incidentally, by the end of the 19th century, exquisite Irish crochet was valued on its own merits, rather than its ability to mimic more expensive laces.