Bust My Buttons

May 23rd, 2011

Tonight I finished putting together the bodice of my Empire dress fairly early. I didn’t quite have the energy to cut out the skirt and waistband though, so I decided to cover a set of five buttons for the center back closure.

From what I can discover online, there were three main types of buttons used on clothing at the turn of the 18th century: metal, fabric-covered, and thread (metal rings wrapped in thread to create intricate designs). Somehow metal seems incongruous on a delicate white frock, and I’ve gotten the impression that the thread buttons (of which Dorset seems to be a classification) are mostly used on undergarments, or things that need to be washed vigorously. So I opted for fabric-covered.

The question then arose as to what I should use for my button forms, and how to attach the covers. Since my time is limited, I decided to use modern buttons from my button box and cover them by gathering tiny circles of fabric around them and sewing it closed. I’ve made a mental note to dig deeper into this topic at a later date.

I made five buttons, which seems like more than sufficient to close the center back of my emerging dress. They’re rather thickish though, so I think I shall make thread loops instead of buttonholes. Even with three layers in the buttonstand, my dress fabric is far too fragile to withstand much strain.

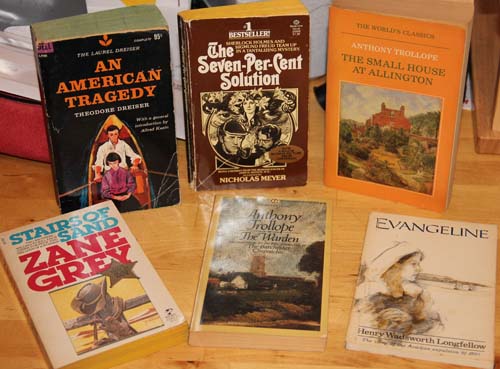

3 Dollars Worth of Literature

May 22nd, 2011

Have I mentioned that I love Housing Works? They run a fantastic Bookstore Cafe on Crosby Street in SoHo that both collects and sells an amazing panoply of used books and records. I finally gave up trying to give away my recent reading material and decided to donate it to Housing Works. In fact, I think I bought most of it there in the first place.

Of course the best part about donating your books when you’re through with them is that it gives you a perfect excuse to scoop up a few new titles while you’re in the shop. Here’s my haul from today’s jaunt:

I always head straight for the 50 cent rack — they may have a little more wear on the spine, but they’re perfect for dragging around the City (I do much of my reading while I walk — yes, I’m that nut you banged into earlier with her nose buried in a copy of Dubliners — at least it’s better than running into people because you’re texting on your mobile phone). So this impressive array cost a mere $3 plus tax. My companion, he of the exquisitely eclectic taste, snagged a Frank Sinatra LP and a first edition of Oboler’s Omnibus. If you don’t know who Arch Oboler was, ask someone who was born before you were.

I actually hated Sister Carrie, and vowed never to read another book by Dreiser. But I know enough about the plot of American Tragedy to have had my curiosity piqued. I’ve never read anything by Zane Grey, but early 20th century westerns are a guilty pleasure in which I indulge too rarely. The Trollopes are because someone (I only wish I could remember who) told me I’d enjoy him more than Hardy. Evangeline needs no explanation; though perhaps I should tell you it holds particular meaning thanks to my fifth grade history project where I recreated an Acadian folk-costume. Last but not least, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution is a silly present for a friend.

Have you read any of these? Tell me what you thought — but please don’t spoil the endings!

Petticoat Acompli

May 21st, 2011

I’m pleased to report that my Empire petticoat is complete! It’s entirely hand-sewn, and despite a skirt that is not quite perfectly balanced, I’m very happy with it!

As revealed in an earlier post, I used a pattern from Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion I: the 1798-1805 morning dress. I simply left off the apron front that would have turned this into a complete dress. The bodice is linen (Arnold’s original had a linen lining to the bodice), but I decided to go with cotton muslin for the skirt — linen would have been far too stiff and heavy.

Here’s the apron part of the skirt — nearly flat at the front, but lightly gathered by the time it reaches the side. It’s set into a very narrow linen waistband that continues to form long ties. The original dress had a front bodice piece attached to this part of the skirt, that buttons on to the rest of the bodice.

The sides and back of the skirt are set into the bodice with a series of pleats at the sides and a small section of gathers at the very back. Also at the back, you’ll see a pair of thread loops that hold the ties from the apron front as they wrap around to tie in front.

I had to resist the urge to over-finish the inside. After running the seams with a modified back-stitch (tiny running stitches with an occasional back-stitch for strength), I trimmed the allowances and overcast them. The neck, arms, and front bodice were simply turned and hemmed.

The skirt is two lengths of 45 inch wide cotton muslin, sewed into a tube at the selvedges (19th-century “sewing” requires no seam allowance when you’re joining selvedges). Since the original pattern called for three breadths of narrower fabric in the skirt, it used the side seams for the apron front opening. My side seams were too far towards the back. Instead, I cut two long slits into the front portion of the skirt and hemmed them with a tiny pleat at the base of the slit. I also hemmed the bottom, and put in two 3/4 inch tucks.

At the top of the skirt, I scooped out an inch from the center front, rising gradually as it came around to the sides. In retrospect, I wish I’d taken more than 1 inch — the bodice rises in the back, pulling the skirt up more than I realized. If I’d followed Arnold’s pattern exactly, this would not have been an issue since the back of her dress has a considerable train that would disguise any shortness.

See how it angles up in the back? You can also see how far back the armscye is set. This is one of the distinguishing markers of an Empire gown, though I rather wonder if mine isn’t a bit extreme.

In the end, I decided not to lace up the front the bodice. In Arnold’s original pattern, she indicates that the bodice lining is simply pinned closed. During the fittings, I was convinced that pins would never hold (the lining provides all the bosom support for this outfit) and that I’d be in constant danger of being stabbed. When I tried it on this morning though, pinned in place, I realized that it really works! So I’m leaving it with pins.

And yes, though cleverly disguised in order to keep this picture viewable, the bodice does not come up high enough to actually cover the bosom. As seen in this picture of the original painting that I’m using for inspiration, the lining is meant to run underneath, supporting, but not concealing.

Now, on to the dress!

Stitching Away

May 20th, 2011

I haven’t had much sewing time in the past few evenings (thanks in part to a humiliating mishap on Tuesday night), but I’m still making steady progress on the petticoat for my Empire gown. Keeping me company, I’ve got everything a girl could ask for: Yesterday USA internet radio, a handsome husband in the easy chair, and my wee sewing bird.

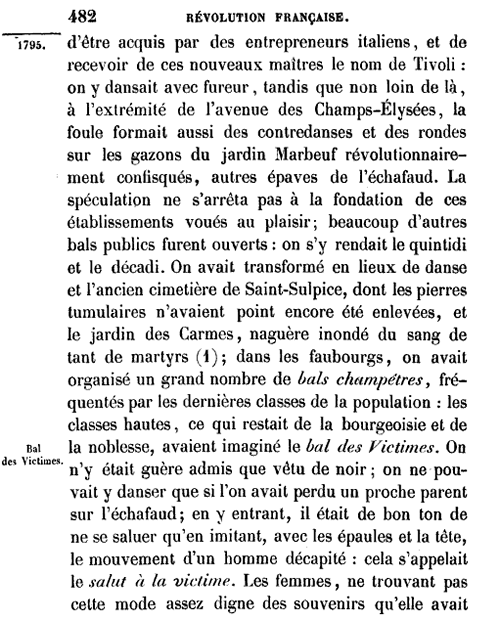

Fashion Victime

May 17th, 2011

There were a number of books and articles published in the mid to late 19th century describing a phenomenon known as Bals des Victimes, that may or may not have taken place in the days following Robespierre’s death and the reinstatement of the French nobility. Here’s a relatively early one from Histoire de la Révolution et de l’Empire, published in 1847.

Unfortunately, my French, limited to begin with, is quite rusty. I believe the gist of this page is as follows:

At the far end of the Champs-Elysees, the crowd of dancers formed on the lawn of some garden that had been confiscated during the revolution, and there were some others around the old gallows of the guillotine. It didn’t stop at the beginning of the red light district either — there were lots of parties open to the public: for five days. They transformed the ancient cemetery of Saint-Sulpice into a dance floor, etc., etc. … In the outlying areas of the city, a great number of pastoral-themed parties were organized, frequented by the latest [lower??] classes. The upper classes, who had been reinstated to the bourgeoisie and the nobility, came up with the Victim’s ball. These were exclusive — in order to get in you had to have lost a parent to the guillotine. Upon entering, it was fashionable to perform a salutation with your head and shoulders imitating decapitation; this was called the Victim’s Greeting.

It goes on, but I cannot.

Here, from an 1867 book about the Empress Josephine, is a description in English:

This was especially the case at the so-called victim balls (bals a la victime) which were given by the heirs, the sons and fathers of those who had perished by the guillotine. People gathered together in brilliant entertainments and balls to the honor and memory of the executed ones. Every one who could pay the large fee of admission to these bals a la victime were permitted to enter. Those who came there, not for pleasure, but to honor their dead, showed this intention by their clothing, and especially by the arrangement of their hair. To remind them that those who had been led to the guillotine had had their hair cut close, gentlemen now had theirs cut short, and the dressing of the hair a la victime was for gentlemen as much a fashion as the dressing of the hair a la Titus (the Roman emperor) was for the ladies. Besides this, the heirs of the victims wore some token of the departed ones, and ladies and gentlemen were seen in the blood-stained garments which their relatives had worn on their way to the scaffold, and which they had purchased with large sums of money from the executioner, that lord of Paris.

As you may guess, I am particularly interested in the fashions associated with this legendary (historians seems to disagree as to whether these events actually took place or were merely figments of later romantic imaginations) custom. A friend who grew up in Paris told me about men and women who wore red ribbons tied round their necks where the blade would have fallen, and there was a fashion for women to wear close cropped hair in imitation of someone about to be executed. Classically inspired robes, like the dress I am in the midst of making right now, were also popular. Some sources claim that attendees wore mourning clothes, including crape bands about the arm. However I don’t know if that type of mourning dress was even invented as early as the turn of the 19th century, which would mark those accounts at least as pure fabrication.

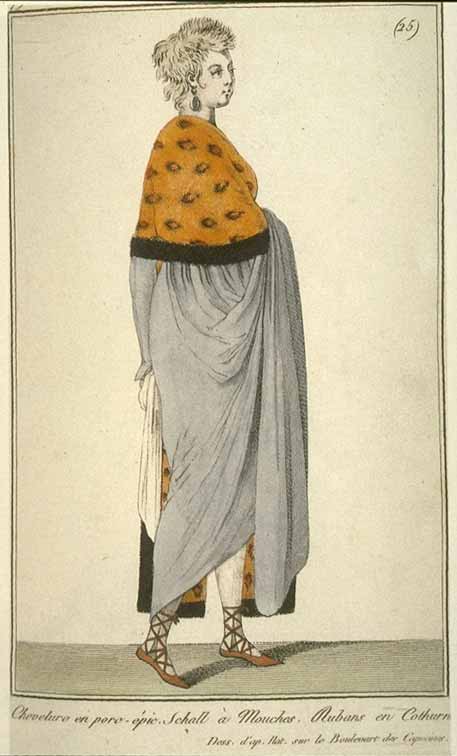

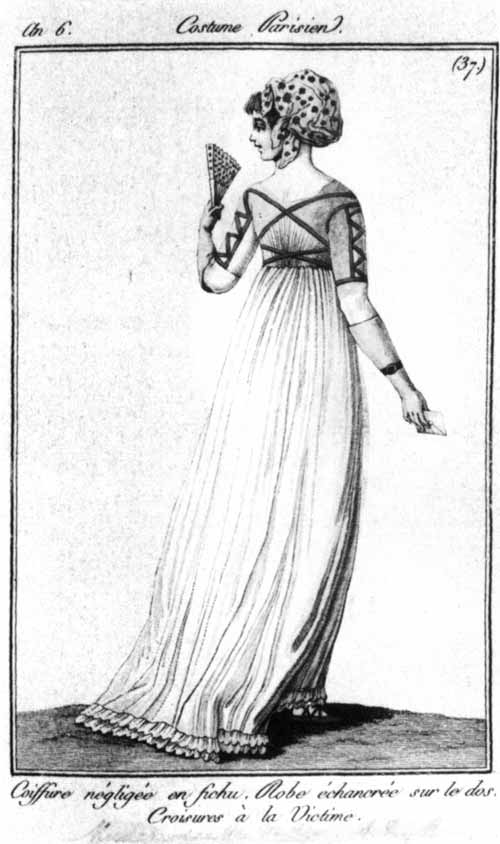

Here are a few fashion plates from late 18th, early 19th century France. Notice how each refers to various styles a la victime?

Very Grecian!

Notice the ribbons bound about her feet — some Victimes wore no shoes, just ribbons tied around their feet and ankles.