Underbust Update

May 16th, 2011

I’m pleased to report some modest progress on my picnic ensemble, despite a busy weekend at work and a persistent headache. So far, I’ve been focused on building a viable under-structure for the bodice of my Empire frock. You’ll notice that I am now calling it Empire, as opposed to Regency, since the dress is taking on more and more of a French influence.

I have to admit I wasn’t too sure that this would work, even after making a quick version in muslin. But the linen under-bodice is really quite remarkable in the amount of support it offers — more than enough to dispense entirely with any thought of additional undergarments. It’s copied from the lining of Janet Arnold’s stomacher-front 1798-1805 morning dress, illustrated and diagrammed on pages 48 & 49 in Patterns of Fashion I.

I cheated and used the copier at work to enlarge the pattern. And, remarkably, had to make very few adjustments to make it fit like a glove: I added an inch to each side of the shoulder strap (I need to add length between the shoulder and bust points on most modern patterns as well) and it looks like I’ll be taking three inches out of the front of the bust (the original dress seems to have belonged to a very well-endowed lady).

Here is my version in progress, including pins marking the center front on my own modest bosom. The original lining in Arnold’s book was pinned closed(!) but I plan to make lacing eyelets as I don’t trust straight pins to hold firmly, or to refrain from stabbing me at an awkward moment. I’m also going to add a long cotton petticoat, possibly with a few tucks at the bottom, to make this a true bodiced-petticoat. The dress will be made separately since it needs to open at the back, while the bust support relies on front closure to achieve its desired effect.

In case you are curious, I’m sewing by hand, so far at least, and finishing by overcasting the seams and hemming the edges. A cursory search turned up no directions for assembling a frock from this period and I’ve never seen an extant example up close, so I am going with the directions from the Workwoman’s Guide, published about 30 years later. Because I was too lazy to go to the laundromat and wash something from my stash of linen, I cut out the bodice from an old linen tea cloth that I purchased at our museum’s stoop sale last Saturday. Lastly, I apologize in advance for the lack of a live-model in this and following “in-progress” pictures. I am not photographing this stage of fitting for obvious reasons.

Hours of Idleness

May 13th, 2011

A Fragment

When, to their airy hall, my father’s voice

Shall call my spirit, joyful in their choice;

When, poised upon the gale, my form shall ride,

Or, dark in mist, descend the mountains side;

Oh! may my shade behold no sculptured urns,

To mark the spot where earth to earth returns!

No lengthen’d scroll, no praise-encumber’d stone;

My epitaph shall be my name alone:

If that with honour fail to crown my clay,

Oh! may no other fame my deeds repay!

That, only that, shall single out the spot;

By that remember’d, or with that forgot.

One of my favorite verses, from Byron’s compendium of verse Hours of Idleness, published in 1807. Clearly Byron achieved his goal, but perhaps not in quite the way he anticipated. I am reminded of this passage from Washington Irving’s essay on Westminster Abbey:

And yet it almost provokes a smile at the vanity of human ambition, to see how they are crowded together and jostled in the dust; what parsimony is observed in doling out a scanty nook, a gloomy corner, a little portion of earth, to those, whom, when alive, kingdoms could not satisfy; and how many shapes, and forms, and artifices are devised to catch the casual notice of the passenger, and save from forgetfulness, for a few short years, a name which once aspired to occupy ages of the world’s thought and admiration.

I passed some time in Poet’s Corner, which occupies an end of one of the transepts or cross aisles of the abbey. The monuments are generally simple; for the lives of literary men afford no striking themes for the sculptor. Shakspeare and Addison have statues erected to their memories; but the greater part have busts, medallions, and sometimes mere inscriptions. Notwithstanding the simplicity of these memorials, I have always observed that the visitors to the abbey remained longest about them. A kinder and fonder feeling takes place of that cold curiosity or vague admiration with which they gaze on the splendid monuments of the great and the heroic. They linger about these as about the tombs of friends and companions; for indeed there is something of companionship between the author and the reader. Other men are known to posterity only through the medium of history, which is continually growing faint and obscure; but the intercourse between the author and his fellow-men is ever new, active, and immediate. He has lived for them more than for himself; he has sacrificed surrounding enjoyments, and shut himself up from the delights of social life, that he might the more intimately commune with distant minds and distant ages. Well may the world cherish his renown; for it has been purchased, not by deeds of violence and blood, but by the diligent dispensation of pleasure. Well may posterity be grateful to his memory; for he has left it an inheritance, not of empty names and sounding actions, but whole treasures of wisdom, bright gems of thought, and golden veins of language.

Regency Indecency

May 12th, 2011

I am attending a neoclassical picnic later this month, and have decided to finally make that Regency-era dress I’ve been putting off for more than a decade. My mother bought me a copy of the Folkwear Empire Dress pattern, along with a length of sheer fabric printed with blue stripes and tiny blue flowers in the late 1990s. At the time, I was working for the George Read II House & Garden, an historic house build in the early 19th century, and had plans to sew an appropriate wardrobe.

So tonight, I grabbed some cheap muslin and cut out the Folkwear bodice. I’d already decided to use the skirt from Janet Arnold instead of making the gored skirt included in the pattern (I’ve never seen a gored Regency skirt…not that I know much about this period). Alas, after hastily stitching the bodice together and gathering it over my corset lace because I was too lazy to hunt for a proper drawstring, I discovered that I also hate the top of this dress. Please don’t misunderstand; it’s a lovely pattern and I adore Folkwear, but it just isn’t what I’m looking for this time.

Here’s what I’m trying to match:

Young Woman in White, circa 1798, oil on canvas,

attributed to the circle of Jacques-Louis David.

Well, perhaps not exactly. I’m not sure I’m brave enough to attend a picnic at a public garden with quite such a visible bust line. But I love the sleeves, the neck, the skirt, the hairdo, the shawl. I think I’ll add a straw hat too.

As for the pattern, I think Janet Arnold is going to be my best friend in this case. So I’m off to con my copy of Patterns of Fashion I. The big question that remains of course is whether she is wearing a bust-bodice or a bodiced petticoat (I am leaning towards the latter based on the volume of her skirts) and IS IT BONED??

P.S. I am saving the original blue striped and flowered material for an 1850s wrapper — it’s far too fussy to be properly Neoclassical — and I’ve pulled out a nice white-on-white striped sheer cotton that’s almost fine enough to be mull.

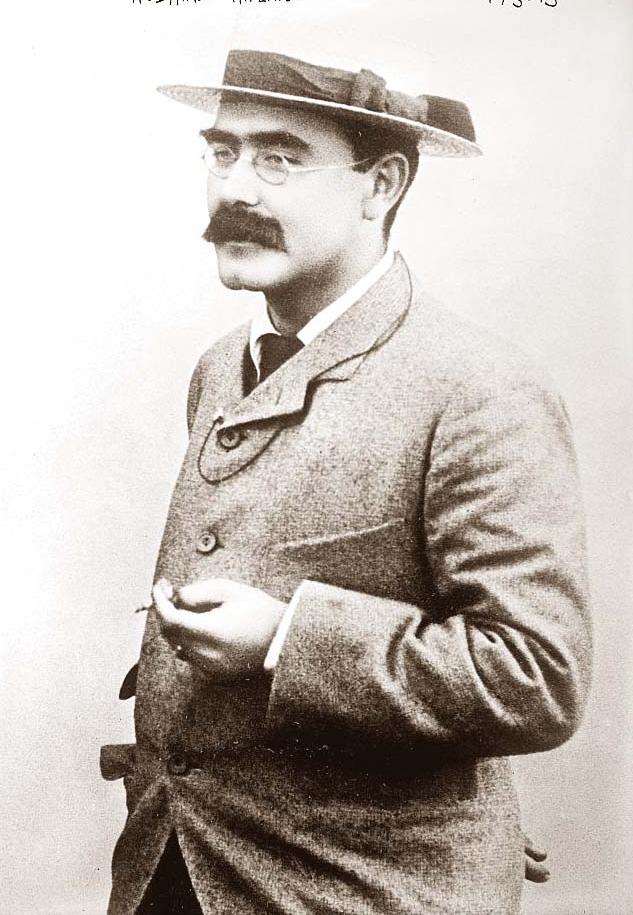

Where’s Rudyard?

May 9th, 2011

I have been conducting an informal survey lately, to see how many of my acquaintance are familiar with the works of Rudyard Kipling, most particularly his “Stalky” stories. So far, the results have not been very encouraging for the Pukka Sahib. Most know who he was, but few have read any of his works — poetry or prose — and none have even heard of Stalky & Co.

So I have decided that the world is in great need of more Rudyard Kipling. If you’re young, or possess a fanciful bent, I recommend Kipling’s Just So Stories. If you haven’t much time to read these days, try grazing your way through the short stories in Plain Tales from the Hills. But for real, pure enjoyment, find a copy of Stalky & Co.

Of course, reading Kipling requires more than a little tolerance. One might characterize him as a misogynistic, xenophobic imperialist. I find his humor makes up for his politics, and his talent for storytelling takes care of the rest. After all, we are talking about the fin de siècle British army…I particularly appreciate my recent re-readings of Kipling since my foray into T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), who wrote in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, “Some of the speed and secrecy of our victory…might perhaps be ascribed to…the rare feature that from end to end of it there was nothing female in the Arab movement, but the camels.” Of course Kipling writes about India, not Arabia, but the attitudes are quite similar.

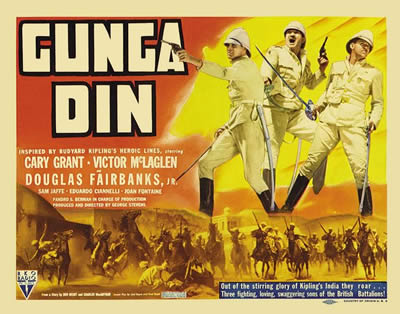

Even if you don’t heed my plea to find a copy of something by Kipling, you can at least read his most famous poem (immortalized in 1939 by a film starring Cary Grant, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and Sam Jaffe in the title role):

GUNGA DIN

YOU may talk o’ gin an’ beer

When you’re quartered safe out ‘ere,

An’ you’re sent to penny-fights an’ Aldershot it;

But if it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An’ you’ll lick the bloomin’ boots of ‘im that’s got it.

Now in Injia’s sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin’ of ‘Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them black-faced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din.It was “Din! Din! Din!

You limping lump o’ brick-dust, Gunga Din!

Hi! slippy hitherao!

Water, get it! Panee lao!

You squidgy-nosed old idol, Gunga Din!”The uniform ‘e wore

Was nothin’ much before,

An’ rather less than ‘arf o’ that be’ind,

For a twisty piece o’ rag

An’ a goatskin water-bag

Was all the field-equipment ‘e could find.

When the sweatin’ troop-train lay

In a sidin’ through the day,

Where the ‘eat would make your bloomin’ eyebrows crawl,

We shouted “Harry By!”

Till our throats were bricky-dry,

Then we wopped ‘im ’cause ‘e couldn’t serve us all.It was “Din! Din! Din!

You ‘eathen, where the mischief ‘ave you been?

You put some juldee in it,

Or I’ll marrow you this minute,

If you don’t fill up my helmet, Gunga Din!”‘E would dot an’ carry one

Till the longest day was done,

An’ ‘e didn’t seem to know the use o’ fear.

If we charged or broke or cut,

You could bet your bloomin’ nut,

‘E’d be waitin’ fifty paces right flank rear.

With ‘is mussick on ‘is back,

‘E would skip with our attack,

An’ watch us till the bugles made “Retire.”

An’ for all ‘is dirty ‘ide,

‘E was white, clear white, inside

When ‘e went to tend the wounded under fire!It was “Din! Din! Din!”

With the bullets kickin’ dust-spots on the green.

When the cartridges ran out,

You could ‘ear the front-files shout:

“Hi! ammunition-mules an’ Gunga Din!”I sha’n’t forgit the night

When I dropped be’ind the fight

With a bullet where my belt-plate should ‘a’ been.

I was chokin’ mad with thirst,

An’ the man that spied me first

Was our good old grinnin’, gruntin’ Gunga Din.‘E lifted up my ‘ead,

An’ ‘e plugged me where I bled,

An’ ‘e guv me ‘arf-a-pint o’ water—green;

It was crawlin’ an’ it stunk,

But of all the drinks I’ve drunk,

I’m gratefullest to one from Gunga Din.It was “Din! Din! Din!

‘Ere’s a beggar with a bullet through ‘is spleen;

‘E’s chawin’ up the ground an’ ‘e’s kickin’ all around:

For Gawd’s sake, git the water, Gunga Din!”‘E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

‘E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ‘e died:

“I ‘ope you liked your drink,” sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ‘im later on

In the place where ‘e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen;

‘E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to pore damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in Hell from Gunga Din!Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Tho’ I’ve belted you an’ flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!— Rudyard Kipling

Last, but not least, my own best beloved just turned me on to this mind-blowing gem (please ignore the incongruous footage from Easy Rider):

To Mother

May 8th, 2011

Mother’s Day, as we know it, was declared a holiday in 1870 by Julia Ward Howe, who grew up not far from where I live and is best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” She originally set the date in June. But odes upon the importance of motherhood are as old as time itself. Here are a couple of gems, complete with illustration, from Godey’s Lady’s Book.

WE do not hear much of the mothers of great men. What their fathers were— what their reputation, qualities, and history— is related to us with great particularity; but their mothers are usually passed over in comparative silence. Yet it is abundantly proved, from experience, that, the mother’ s influence upon the development of the child’s nature and character is vastly greater than that of a father can be. “The mother only,” says Richter, “educates humanly. Man may direct the intellect, but woman cultivates the heart.” — Godey’s Lady’s Book, May 1854

THE MOTHER’S BLESSING

“MY mother ! my first, best friend! As I sit here, looking far back into the past, I can trace in every act that did me credit the influence of her love her tender care; and on every unworthy deed I seem still to see the sad, grieved face, the brimming eye, and, quivering lip she bent over me, trying, by sweet, winning love, to bend my stubborn will; and make me regret the act that caused her so much sorrow. Surely, the best gift in our heavenly Father’s sending is mother’ s love.” — Godey’s Lady’s Book, Mary 1858

Happy Mother’s Day!

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »