Portrait of a Lady (Duff Gordon)

December 13th, 2012

Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon has been on my mind of late. Mostly because I am making yards upon yards of tatted lace trim, loosely based on one of her published patterns. I was curious to know what she’d done to rate her own volume of fashionable tatting patterns, so I looked her up. Color me astonished. Not only was she a leading character of the early 20th-century fashion scene, she was also a woman after my own heart.

- Her maiden name was Sutherland, which may or may not mean a connexion to the Scottish clan of which my ancestors, the Grays, were a sept.

- When faced with financial ruin, she turned to her needle for support, opening a small dressmaker’s shop in turn-of-the-century London.

- She designed the costumes for a London production of The Merry Widow (a favorite of myself and my grandmother) in 1907.

- She was a pioneer of modern fashion culture; her Lucile Ltd. shop featured elegant shopping experiences, complete with live models and afternoon tea. Afternoon tea!!

- Lucy created one-of-a-kind “personality” dresses for her more important clients, spending days getting to know them before making their outfits.

- She, like me, was obsessed with lingerie. In fact, that’s the one part of her label that has survived to this day.

- In addition to tatting patterns, Lucy branched out to design everything from film costumes to car interiors. Yes, car interiors. Those were the days!

Perspectives on Labor Day, 1888

September 3rd, 2012

The idea of setting aside a day to celebrate the growing Labor movement was first proposed in New York City in 1882. This illustration shows the first Labor Day parade down what looks like lower Broadway, near City Hall. I wonder if they started in Union (get it?) Square…

Over the ensuing decade, before Labor Day was declared a national holiday in 1894, 30 other states gradually adopted the early September observance on their own. New York State made it official in 1888.

Looking for a pithy quote from an early NYC Labor Day, I searched The New York Times’s excellent archive (thank you NYT for making it free again). The coverage I found was so blatantly against Labor Day and all it represents, that I decided to look in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as well. There, in the morgue (hosted by Brooklyn Public Library) of the paper once edited by people’s poet Walt Whitman, I found an article so perfectly opposed to The Times diatribe, that I couldn’t resist, despite the verbosity, sharing them both here in their entirety.

What’s especially interesting in this election year of 2012 — 130 years after that first Labor Day — is how little the messages on Labor have changed. Particularly in The Times. You may think you are reading Conservative talking points for a speech to be delivered next week, rather than something written more than a century ago. I won’t make any other comments of my own. This isn’t a political blog, and I’m mostly interested in what was, not what will be. But I certainly hope you’ll take the time to read the articles and come up with your own ideas about how far we’ve come.

Note — in 1888, Brooklyn and New York were separate cities.

Monday, September 3, 1888

The Brooklyn Daily EagleLabor Day.

The addition of another holiday to the few observed by Americans was in itself a notable fact. The addition was not made hastily or by any forcing process. The attempt was put forth for several years, until it massed behind it a sentiment that had to be taken into account. Then a Republican Legislature concurred with the request of a Democratic Governor. The result was the present law creating Labor day and making it a holiday. The idea originated with the labor men themselves. They chose the time as well as initiated the proposition. They purpose was to signalize the common interests and sympathies of all the songs of toil. The period selected was thought to represent a date in the year which would hamper few, if any, enterprises and which would also be conveniently remote from other days of observance in the nation or in the State [New York].

…

The accounts in the Eagle of Friday, Saturday, Sunday and to-day indicate that in Brooklyn Labor day will receive an observance worthy of its purpose and of its name. Between employees and employers in this city is peace. Between the various departments of organized Labor is concord. The year past and ending to-day has been one, in the main, of industrial tranquility in this community. The grand divisions of the great army of Labor to-day march under banners of agreement. The display made to-day is one that powerfully affects the sympathy and the imagination of the people. It emphasizes the consciousness of Labor touching its own strength. It attests and vindicates the fact that that transcendent strength has not been abused within the limits of the third city of the Union. It is also an unspoken, but a tacit admission that Labor is strong, because it has aligned itself with something even stronger than itself, namely, the collective Public Opinion of which it is so potential a part.

Truly, in aligning itself with that Public Opinion, Labor has acted more quickly and more wisely than any like organization of equal magnitude in the history of these States. Labor has learned that it is invincible, when it is right, and that it is right when it realizes that its best interests and the best interests of capital are, if not identical, certainly as much related as the two sides of a single shield. Those who would maintain that these interests are hostile have been wise neither for Labor nor for capital. The human strength of the one and the corporate or associated strength of the other were meant to be friends and not enemies. Only a mistaken selfishness could, even for a brief while, think the contrary. Only a wicked selfishness could, in the captivating light of educating experience, long maintain the contrary. Against the demagogues who, without labor, would live on Labor, by exciting it to distrust and dissension, the armies of workers most need to protect themselves. Against the hard and absolute minds that would make of capital a tourniquet with which to compress the arteries of industrial energy, the forces of employers need to guard themselves. When employees and employers meet face to face, themselves or their intelligent representatives find an hundred points of agreement for any one of difference, and so will they and should they always find.

On this point the Eagle can speak with authority. Considered as a place of work, the Eagle represents a large number of employees and a body of employers between whom the most amicable relations of mutual interest prevail, and it, therefore, knows whereof it speaks. Every day’s issue of this paper and every day’s business of this establishment represents the accordant labor of hundred of brains and hands working not merely for themselves and one for another, but consciously put in the trust of the narration of the news, views and announcements of a vast community. Mutuality of interest creates a unity of feeling and coincides with a measure of uncoveted prosperity never before so great as now. The like experience has been that of hundreds of other centers of work in this and in sister cities and each day thus becomes a business proof of the entire compatibility of the relations of employees and employers with the best of feeling and with the highest degree of reciprocal energy. Every one regards himself as part of the Eagle and is desirous of its prosperity and proud of its achievements.

Organized Labor knows its rights and frowns on those who would abuse its powers. Itelligent capital, realizing that it is put in trust of forces; for which it must render an account to God and to humanity, knows that in intelligent Labor it has its best ally and the creator of its prosperity and security. Labor day can emphasize these truths and, when it is observed in the spirit of the present time, it does emphasize them so plainly and so loudly that not the dullest can fail to understand the fact nor the deafest fail to hear the strains of the harmony as those strains stir the banners of the songs of toil “with the music in the air.”

And just a day later…

September 4, 1888

The New York TimesYesterday was the first occasion on which, in this city at least, a very general and systematic approach was made for a public observance of Labor Day. The result was a procession, not very large in number, but made noteworthy by the highly respectable and prosperous appearance of those who composed it, and an enormous concourse of people along the line of march.

Any disinterested American observer of mature years must have been impressed by the change that the procession denoted from the social conditions of his boyhood. Up to the outbreak of [civil] war there was no such sharp division of classes as the parade of “organized labor” now exhibits. There were of course many factories in the country, of which the capital was subscribed by persons who had no personal connection with the business, which was conducted by operatives, who in turn had no personal interest in the profits apart from their wages. But the business of working in these factories was a casual and temporary employment for boys and girls who had no expectation of passing their lives as operatives, and who by no means identified themselves with the “operative class.” The trades of the country were for the most part conducted by men who were both laborers and, on a small scale, capitalists, and to whom talk about the antagonism of the labor and the capital in their business would have been absolutely meaningless. They employed such assistance as they needed from time to time, or permanently, just as the farmer did; and they got this assistance as cheap as they could, just as the farmers did then and as the capitalists do now. But the men they employed looked forward to a time when they too should be able to set up for themselves, and it no more occurred to them that they were of a different class from their employers than the same thought occurred to the farmer’s “hired man.” They would have seen no more sense in a proposition to set a day apart and call it Labor Day than in a proposition for the observance of Capital Day. Everybody was a laborer, and everybody looked forward to being a capitalist.

Of course, with the natural increase of population and much more with its artificial increase by immigration, such a simple and primitive condition of society could not last, but it is to the interest of the whole community, and especially to the interest of its poorer members, that it should last as long as possible. Yet the course of conduct adopted and of legislation instigated by the representatives of the men who work for wages has the effect of making them a class apart and of emphasizing the distinctions that exist between them and other members of the community. Their action, in a word, tends to Europeanize the social and industrial conditions of the United States. The very phrase the “solidarity of labor” indicates a belief on the part of those who use it that all men who work for wages will continue to work for wages so long as they live, and that it is to their interest to do as little for “capital” and get as much from it as may be. The policy of the trades unions to some extent, and still more of the extensive labor organization, tends to bring about this condition. Their regulations make it very much harder than it would otherwise be, and in some cases make it impossible, for a capable and ambitious workman to get on faster, by superior ingenuity or industry, than the incapable and unambitious workman. What the capable and ambitious workman desires is the liberty to make his own agreements and to secure higher than the average pay for more and better than the average work. This, in fact, is the only way in which a workman can better his position, except by superior frugality. But this is entirely contrary to the spirit of “organized labor,” and in most trades a man who attempts it will find that he cannot do it without breaking the rules of the labor organization to which he belongs. The effect of this way of thinking and of acting is to make “labor” a caste to which a man is born and from which it is almost as hard for him to escape as if he were a Hindu; and “labor” itself is far more responsible for this result than is capital.

It was not clear when the act establishing “Labor Day” was passed what was expected to be gained by it; nor does the observance of the day help us to understand. There was no address yesterday which pretended to set forth the need of Labor Day, or the advantages that are to accrue from its observance. The celebration was merely a “demonstration.” It showed, in an impressive fashion, that there are many workers for wages who are willing to transfer to labor unions their lawful right to make their own agreements with their employers, and who wish to be known, not as American citizens having a common interest with other American citizens, but as a special class having a class interest apart from, or hostile to, the general interest.

And here’s just one more little snippet describing the Brooklyn Labor Day parade, from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, published on September 4, 1888. Interesting point which plays into Bernard Shaw’s insistence that organized labor was just as much opposed to socialism as the capitalists.

…There was a marked absence of red, the only case where there was any exhibition of this kind was on the Stars and Stripes borne by the United Carpenters. Above and below the flag were tied bows of red ribbon, but they attracted no attention. One of the marshals of the Blue Stone Cutters said that no Socialistic emblems would be permitted…

Ha! And to think I just decorated the Lodge with red paper streamers for our own Labor Day picnic…the things we do in ignorance…

Scholarship Surfaces

July 25th, 2012

Remember that “shocking” finding at Innsbruck I wrote about last week that seemed to disprove everything anyone had ever believed about Medieval underwear? BBC History Magazine has posted a non-sensationalized article about it, complete with comments by the costume historian who is researching the finds. Well done! And well done Katy of “The Fashion Historian” for sharing it with the rest of us.

Here is a link to the new article.

I had plans to create another post featuring the second picture that’s been going around, explaining how this “string-bikini bottom” might very well be similar to garments described by 19th-century health manuals, to be worn by menstruating women, but that is well covered by Ms. Nutz, the textile historian quoted in the above article. So I will desist.

Really, Really Old Underwear

July 17th, 2012

My fascinating friend, and 19th-century warrioress extraordinaire, Rachel posted a link to this article about a recent discovery by the archaeology department of the University of Innsbruck. They seem to have found evidence of hitherto unknown forms of fifteenth-century undergarments in an Austrian castle. If you’ve read any of my previous postings, you know I’m a sucker for a good historical underwear discovery.

The article is a little misleading however, as it doesn’t point out that this brassiere look-a-like is actually missing a large chunk of material that would have covered the stomach from breasts to waist, and likely a back portion that laced on at the sides and anchored the other end of the shoulder straps. See the piece with lacing eyelets hanging down the left side? It probably survived because it was reinforced.

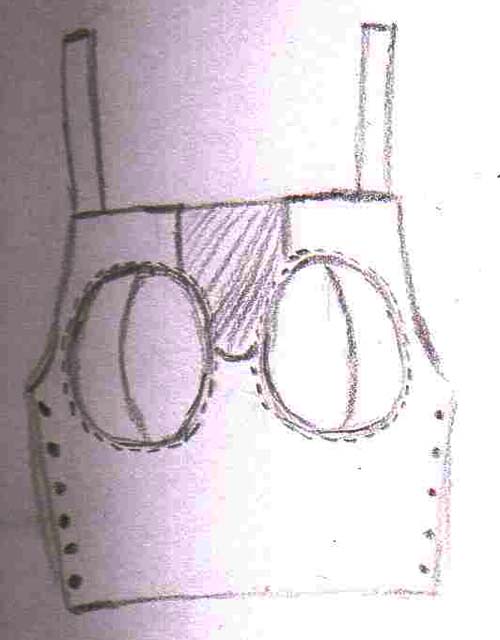

Here’s my hastily drawn rendering of what it might look like with the missing material.

I’m undecided about what’s going on between the breast cups at the top. Is it purposefully left open because fifteenth-century German underdresses (worn over underwear, but under the overdress) often had deep V necks? Or was there a different, finer, or even decorative fabric inserted there? The top edge looks like it was meant to end where it does, but it may also just be impossible to see in the picture that it’s also ripped and the same material once ran all the way across.

I also wonder how much of a revelation this actually is. I’m incredibly ignorant about fifteenth-century Germanic fashion, so I looked it up in “A History of Costume” by Carl Köhler, a 19th-century costume historian. In the section on fifteenth-century German women’s dress, he tells us:

“A chronicler of the day describes this fashion [a new form of dress in the late 1400s) thus: ‘Girls and women wore beautiful wimples, with a broad hem in front, embroidered with silk, pearls, or tinsel, and their underclothing had pouches into which they put their breasts. Nothing like it had ever been seen before.’ “

Hmmmm. But, as I said, I know next to nothing about this period. So I am happy to take the word of those who do that this is a remarkable discovery. There’s another garment featured in the article, and I also have a few ideas about that. But I’ll save them for another post.

In the meantime, if you run across a more scholarly treatment of this topic, please let me know. I’d be anxious to hear some of the finer points describing the findings and why they are so surprising.

E’en Tho’ It Be a Cross

April 15th, 2012

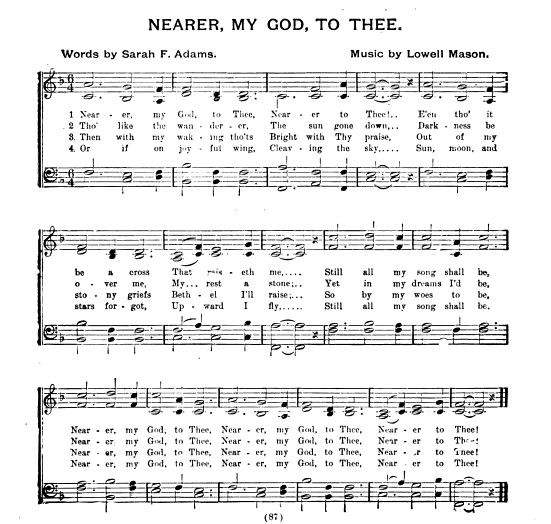

Today being the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, I was reminded of the beautiful old hymn that famously played while the great ship went down. Namely, Nearer My God to Thee.

I learned to play Nearer My God to Thee a few years ago for our annual funeral reenactment at the Merchant’s House Museum. It’s not actually a funereal hymn, but the one we’d been using, When Our Heads Are Bowed with Woe, was too obscure for the participants to follow on first hearing. A few months later, I recorded the hymn on the Museum’s 1850s harmonium so that it could be played at subsequent reenactments. There’s really nothing quite like 75 voices raised in a 150-year-old hymn, marching through the streets of the East Village.

My dear friend over at Costume & Construction sent me a link to this early wax cylinder recording of Nearer My God to Thee.

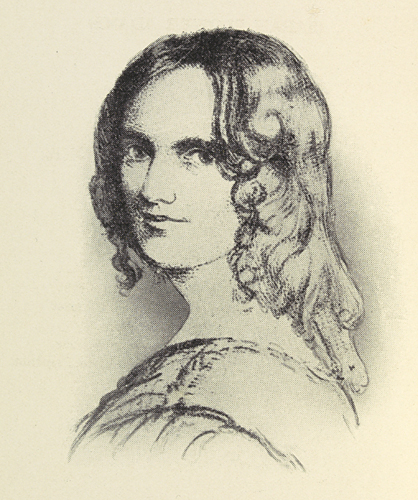

Sarah Flower Adams

The life and story of the poetess who wrote the immortal words is summarized in Illustrated History of Hymns and their Authors, 1875.

This language was the heart-utterance of Mrs. Sarah Flower Adams, daughter of Benjamin Flower, editor of The Cambridge Intelligencer, and wife of William B. Adams, an eminent engineer, and also a contributor to some of the principal newspapers and reviews.

She was born February 22, 1805.

Her mother is described as a lady of talent, as was her elder sister Eliza, who was also an authoress.

She was noted in early life for the taste she manifested for literature, and in maturer years, for great zeal and earnestness in her religious life, which is said to have produced a deep impression on those who met with her. Mr. Miller says: “The prayer of her own hymn, ‘Nearer, my God, to Thee,’ had been answered in her own experience. Her literary tastes extended in various directions. She contributed prose and poetry to the periodicals, and her art-criticisms were valued. She also wrote a Catechism for children, entitled ‘The Flock at the Fountain’ (1845). It is Unitarian in its sentiment, and is interspersed with hymns. She also wrote a dramatic poem, in five acts, on the martyrdom of ‘Vivia Perpetua.’ This was dedicated to her sister, in some touching verses. Her sister died of a pulmonary complaint* in 1847, and attention to her in her affliction enfeebled her own health, and she also gradually wore away, ‘almost her last breath bursting into unconscious song.'” Thus illustrating the last stanza:—

“Sun. moon, and stars forgot,

Upward I fly,

Still all my song shall be,

Nearer, my God, to Thee.”She died August 13, 1849, eight years after the issue of her popular hymn, and was buried in Essex, England.

*Almost certainly consumption (tuberculosis), explaining Sarah’s subsequent decline after caring for her ailing sister. Very few people who died of tuberculosis during the 19th-century — and there were so many who did — were admitted to have perished from the disease, so great was the fear and prejudice associated with it.