An Unexpected Ending

February 6th, 2011

For the past week I’ve been reading Far from the Madding Crowd. Until today, it was my considered opinion that the chief of Thomas Hardy’s talent lay in his singular ability to invent unsympathetic characters and subject them to well-deserved tortures for more than 400 pages at a time. At first I was merely disgusted, but eventually I began to enjoy the idiotic wranglings of Bathsheba and Sergeant Troy and Farmer Boldwood. I even sneered knowingly at Shepherd Oak’s doormat-like inclinations. At least the pace of the book was agreeably quick — with the protagonists spinning quickly downward in their rush to ruin.

But then the ending drew near, and I turned the pages feverishly waiting for the shoe that never dropped. What came instead was one of the most delightfully wry, pulled-punch endings I’ve ever read. Unlike Great Expectations, where the ending most of us know is famously tacked on, this one clearly belongs (in my opinion at least). And it proves that Hardy knew I was laughing at his melodramatics, and was laughing right back at me all along. As usual, I won’t tell you a morsel more for fear that you may decide not to read it for yourself.

We walked past Housing Works (a second-hand bookstore whose profits go to help New Yorkers living with AIDS — as if I needed yet another reason to buy books) on our way back from an Orchard Street excursion this afternoon. As soon as I knew we were going to stop, I decided to keep my eye out for a copy of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Fate must have been on my side, for there, on the fifty cent book rack (as if you needed yet another reason to visit Housing Works yourself), was a battered copy of the very text I sought. Ridiculous as it may seem, there was a 30 percent sale in effect, so the actual price was even less.

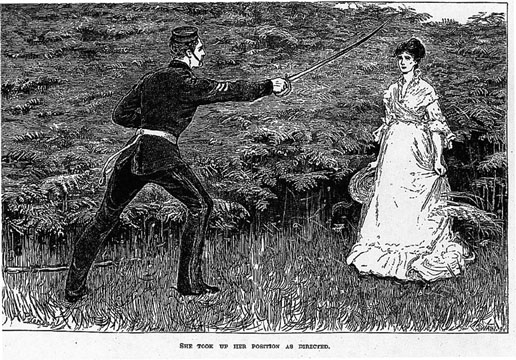

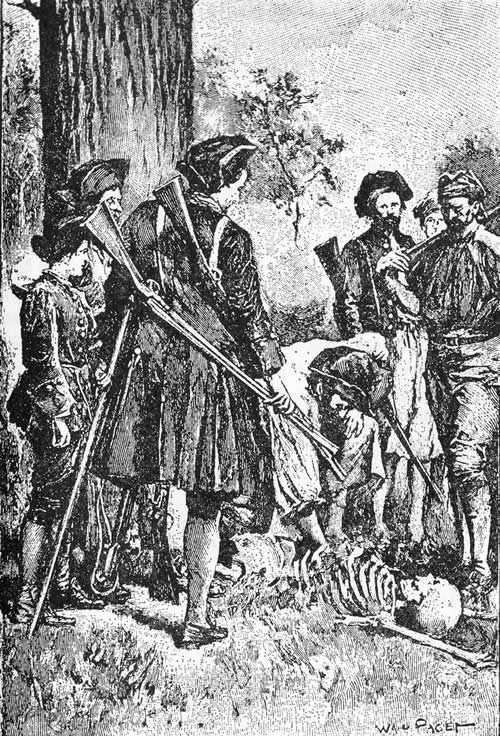

“Hands Were Loosening His Neckerchief” by Helen Patterson Allingham, Cornhill Magazine (February 1874)

I am eager to read more of Hardy. I enjoy his easy mix of rich, descriptive prose and head-whirling action. Stilly drawn scenes of English country life — in his fictional county of Wessex — offer a bucolic backdrop for a plot that is anything but expected. I have been used to narratives where every move is contemplated and hinted at ad nauseum for chapters (perhaps an effect of early publishing methods, where books were released in installments), so it’s a refreshing change to find such drastic occurrences in quick succession.

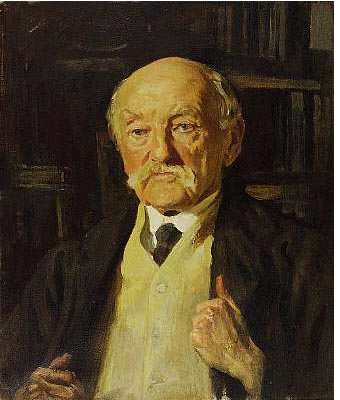

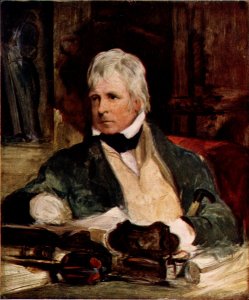

Thomas Hardy by Reginald Eves

Writing in the 1870s, Hardy, like Henry James and Edith Wharton, seems to be foreshadowing modern literature. He has not given up the conventions of the 19th century novel, but he steers clear of the moralizing and judgment (except by proxy, through his characters) that was so rampant a few decades earlier. Also like James and Wharton, Hardy seems to write as an observer looking back, almost longingly, to a simpler time — at least as seen through his thoroughly industrialized eyes. I see hints of the bleakness that bothers me in many fin de siecle and early 20th century works, however there remains a certain reverence that I find most agreeable.

Nightingale

January 27th, 2011

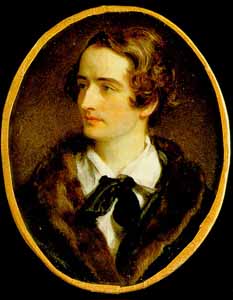

Here, in a portrait that I’m not sure who painted, is the youthful poet John Keats (1795-1821).

He died of consumption before his 26th birthday, a martyr to what was considered one of the most romantic ways to go in the 19th century. (Tuberculosis was idealized partly because of the slow progress of the disease, giving ample time for touching farewells.) As sad as we are that the world can never read the verses that Keats might have written in his 26th and 27th years, it is fortunate in a way that he wasted away into ethereal frailty rather than descending into the libertine coarseness of say, George Gordon.

George Gordon, who wrote in 1821:

Who killed John Keats?

‘I,’ says the Quarterly,

So savage and Tartarly;

”Twas one of my feats.’Who shot the arrow?

‘The poet-priest Milman

(So ready to kill man),

Or Southey or Barrow.’

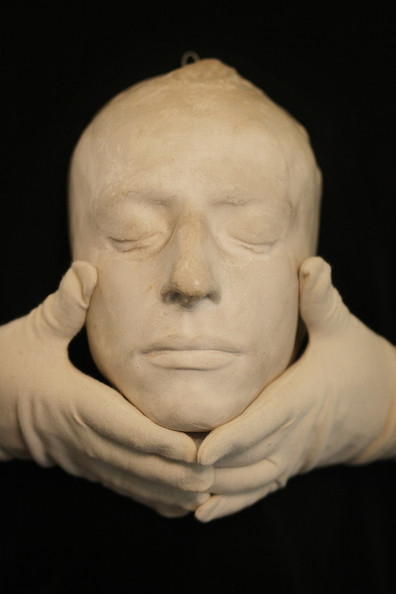

Isn’t John Keats beautiful, even in death? Before photography, the only way to capture a truly accurate image, without involving artistic interpretation, was to make a mask — usually after death. The finest details are captured in a death mask, even down to the eyelashes. They are uncanny, but quite entrancing once you get used to them.

I have no idea why I decided to write about John Keats tonight. Or why I didn’t include any of his poetry in this post.

Adventure at Sea

January 15th, 2011

After finishing Ivanhoe last weekend, I read two whole pages of Milton before gravitating towards a copy of Treasure Island. This was my first foray into the world of Robert Louis Stevenson, unless you count a badly abridged version of The Strange Tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde that I found in my parents’ Everyman Library.

It was definitely the kind of story, and told in such a fashion, to appeal most strongly to a small boy. I must admit that many of the nautical terms soared as far over my head as the main mast (or is it the boom) of the Hispanolia did over Jim’s. And the constancy of the action was a bit wearing as well. Always getting captured, breaking free, shooting muskets, etc. No time to catch one’s breath at all.

I did enjoy the sense that I was reading doubly historical fiction, since Stevenson was writing an 18th century story in the later part of the 19th century. I question his accuracy on a number of points though; Margaret Mitchell got quite a few things wrong when she was writing Gone With the Wind over half a century after the Civil War, for example.

Overall, it was an enjoyable tale and easy to read. In addition, Treasure Island is the source of most pirate conventions and many well-worn characters: “Barbeque,” “Long John Silver,” “pieces-of-eight,” etc. I believe J. M. Barrie must owe a great deal of his inspiration for Peter Pan’s adventures among the pirates to Treasure Island. I am always on the look-out for the books that inspired my pet authors. It makes the later works even more enjoyable, to know from where their bits and pieces came.

Milton lays accusingly on my desk. My gaze shifts uneasily to a bookshelf on the other side of the room, hoping for yet another postponement…

Not-So-Subtle Scott

January 10th, 2011

I discovered Sir Walter Scott in August 2008, while spending four weeks flat on my back (thanks to a very silly bicycling injury), next door to a private library established at the turn of the last century. Most of the strictly literary tomes in said library were published in the mid to late-19th century, amongst whose number I found a slim volume containing an 1860s edition of “The Lady of the Lake” (1810). Later that year, I begged a copy of “Marmion” (1808) from my indulgent husband. I became so fond of Sir Walter Scott’s minstrelsy, I even proposed a theory that his rhymes don’t sound forced when read with an early 19th-century Scottish accent.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

This past summer, while accompanying the partner of my fate on a mission to find Hubert Selby’s sole cheerful novel, my eye was caught by a bargain edition of Ivanhoe (originally published in 1819 under a pseudonym). Scott, Selby — they share shelf. Having never delved into Scott’s prose, I decided to take it home with me and see how I got on. I finally picked up Ivanhoe over Christmas, still eager to avoid finishing Milton.

“Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones — It is not fair. — He has Fame & Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking bread out of other people’s mouths.”

Jane Austen, 1814 (who mentions Sir Walter Scott’s poetry in her own novel, Persuasion.)

Miss Austen may have had a point. Ivanhoe is a delightful read. It’s quicker and more exciting than his poetry, though somehow a little less satisfying from a technical point of view. On the other hand, by leaving behind the delights and challenges peculiar to verse, one can focus completely on the story. And what a surprise lays in store there for the unwary reader!

While the story is set in post-conquest England, amid the final struggles betwixt Norman and Saxon races, not to mention the doings of characters like Richard Coeur-de-Lion and Robin Hood, its real theme is antisemitism. The horrible treatment received by the two central Jewish characters, clearly not condoned by the author, incites sympathy and admiration for their strength under trial as well as disgust for the rest who perpetrate (or at least witness without protest) these atrocities. Even the conclusion seems purposefully unsatisfying, as if we are being left to question how much better might things have been without this terrible prejudice against Isaac and Rebecca.

Alfred Bunn, who “compiled” Ivanhoe into a three-act play shortly after its publication, may have had the right of things when he titled his version Ivanhoe; or, the Jew of York. He at least perceived who was the true hero of the narrative — or the father of the heroine. It also makes me wonder about the state of antisemitic feeling in 1820s England. I know there was a great deal of it towards the end of the 19th century, but Scott at least seems to have felt otherwise at the beginning. Not that he was completely free from the ugly stereotypes of the time of course, or that the book doesn’t contain many things that would surely offend today, but his sympathies were unquestionably engaged.

Here, in an early illustration, we see the brave and beautiful “Jewess” about to prove her mettle by jumping from a turret to avoid a fate worse than death.

I shan’t sport with your intelligence by telling you any more about the plot. You’ll have to read it for yourself, or at least watch the movie with Robert Taylor, Joan Fontaine, and Elizabeth Taylor (though I hear that varies quite a bit from the book).

I must say though, it is refreshing to read a book written when literary devices such as characters remaining unrecognized by their own families while wearing ridiculously flimsy disguises were still relatively fresh. The essay at the beginning of my edition (which I only read as an after thought, to confirm my own surprise at the book’s unexpected overtones) also credits Scott with providing inspiration for the Ku Klux Klan via the scene of Rebecca’s trial by the white-robed Grand Master of the Templars. Oops. I guess I revealed a bit more.

Ivanhoe, kneeling before his childhood sweetheart (an utterly insipid, perfectly blond Saxon damsel) is completely unknown, thanks to his funny hat.

Now go get your own copy of Ivanhoe, or borrow mine if you like. Make a bowl of popcorn, find a pleasant chair, light a few extra candles, and enjoy.

Dressing for D.H.

December 19th, 2010

Earlier this fall, two unrelated events happened to coincide, with a very odd result.

The first item is that I was reading D.H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love — partly because I love D. H. Lawrence, partly because I love T.E. Lawrence (who also loved D.H. Lawrence), and partly because I will read anything to avoid finishing Paradise Lost. I should have read The Rainbow first of course, but I didn’t know any better. I still like Lady Chatterley the best anyhow. (Has anyone else noticed that many of Lawrence’s male protagonists are frail, bearded, with deep set eyes, and prone to coughing?) Read on…

« Newer Posts — Older Posts »