An Unexpected Ending

February 6th, 2011

For the past week I’ve been reading Far from the Madding Crowd. Until today, it was my considered opinion that the chief of Thomas Hardy’s talent lay in his singular ability to invent unsympathetic characters and subject them to well-deserved tortures for more than 400 pages at a time. At first I was merely disgusted, but eventually I began to enjoy the idiotic wranglings of Bathsheba and Sergeant Troy and Farmer Boldwood. I even sneered knowingly at Shepherd Oak’s doormat-like inclinations. At least the pace of the book was agreeably quick — with the protagonists spinning quickly downward in their rush to ruin.

But then the ending drew near, and I turned the pages feverishly waiting for the shoe that never dropped. What came instead was one of the most delightfully wry, pulled-punch endings I’ve ever read. Unlike Great Expectations, where the ending most of us know is famously tacked on, this one clearly belongs (in my opinion at least). And it proves that Hardy knew I was laughing at his melodramatics, and was laughing right back at me all along. As usual, I won’t tell you a morsel more for fear that you may decide not to read it for yourself.

We walked past Housing Works (a second-hand bookstore whose profits go to help New Yorkers living with AIDS — as if I needed yet another reason to buy books) on our way back from an Orchard Street excursion this afternoon. As soon as I knew we were going to stop, I decided to keep my eye out for a copy of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Fate must have been on my side, for there, on the fifty cent book rack (as if you needed yet another reason to visit Housing Works yourself), was a battered copy of the very text I sought. Ridiculous as it may seem, there was a 30 percent sale in effect, so the actual price was even less.

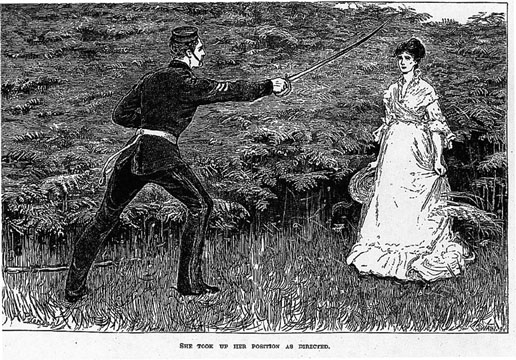

“Hands Were Loosening His Neckerchief” by Helen Patterson Allingham, Cornhill Magazine (February 1874)

I am eager to read more of Hardy. I enjoy his easy mix of rich, descriptive prose and head-whirling action. Stilly drawn scenes of English country life — in his fictional county of Wessex — offer a bucolic backdrop for a plot that is anything but expected. I have been used to narratives where every move is contemplated and hinted at ad nauseum for chapters (perhaps an effect of early publishing methods, where books were released in installments), so it’s a refreshing change to find such drastic occurrences in quick succession.

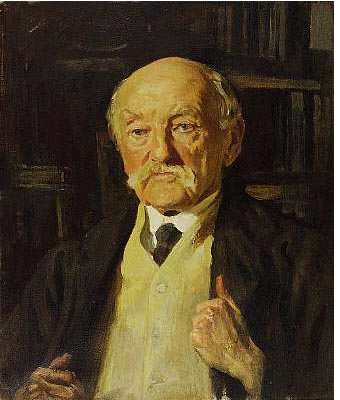

Thomas Hardy by Reginald Eves

Writing in the 1870s, Hardy, like Henry James and Edith Wharton, seems to be foreshadowing modern literature. He has not given up the conventions of the 19th century novel, but he steers clear of the moralizing and judgment (except by proxy, through his characters) that was so rampant a few decades earlier. Also like James and Wharton, Hardy seems to write as an observer looking back, almost longingly, to a simpler time — at least as seen through his thoroughly industrialized eyes. I see hints of the bleakness that bothers me in many fin de siecle and early 20th century works, however there remains a certain reverence that I find most agreeable.

[…] Far From the Madding Crowd, by Thomas Hardy […]