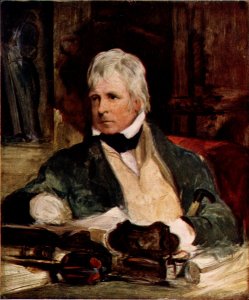

Not-So-Subtle Scott

January 10th, 2011

I discovered Sir Walter Scott in August 2008, while spending four weeks flat on my back (thanks to a very silly bicycling injury), next door to a private library established at the turn of the last century. Most of the strictly literary tomes in said library were published in the mid to late-19th century, amongst whose number I found a slim volume containing an 1860s edition of “The Lady of the Lake” (1810). Later that year, I begged a copy of “Marmion” (1808) from my indulgent husband. I became so fond of Sir Walter Scott’s minstrelsy, I even proposed a theory that his rhymes don’t sound forced when read with an early 19th-century Scottish accent.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832)

This past summer, while accompanying the partner of my fate on a mission to find Hubert Selby’s sole cheerful novel, my eye was caught by a bargain edition of Ivanhoe (originally published in 1819 under a pseudonym). Scott, Selby — they share shelf. Having never delved into Scott’s prose, I decided to take it home with me and see how I got on. I finally picked up Ivanhoe over Christmas, still eager to avoid finishing Milton.

“Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones — It is not fair. — He has Fame & Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking bread out of other people’s mouths.”

Jane Austen, 1814 (who mentions Sir Walter Scott’s poetry in her own novel, Persuasion.)

Miss Austen may have had a point. Ivanhoe is a delightful read. It’s quicker and more exciting than his poetry, though somehow a little less satisfying from a technical point of view. On the other hand, by leaving behind the delights and challenges peculiar to verse, one can focus completely on the story. And what a surprise lays in store there for the unwary reader!

While the story is set in post-conquest England, amid the final struggles betwixt Norman and Saxon races, not to mention the doings of characters like Richard Coeur-de-Lion and Robin Hood, its real theme is antisemitism. The horrible treatment received by the two central Jewish characters, clearly not condoned by the author, incites sympathy and admiration for their strength under trial as well as disgust for the rest who perpetrate (or at least witness without protest) these atrocities. Even the conclusion seems purposefully unsatisfying, as if we are being left to question how much better might things have been without this terrible prejudice against Isaac and Rebecca.

Alfred Bunn, who “compiled” Ivanhoe into a three-act play shortly after its publication, may have had the right of things when he titled his version Ivanhoe; or, the Jew of York. He at least perceived who was the true hero of the narrative — or the father of the heroine. It also makes me wonder about the state of antisemitic feeling in 1820s England. I know there was a great deal of it towards the end of the 19th century, but Scott at least seems to have felt otherwise at the beginning. Not that he was completely free from the ugly stereotypes of the time of course, or that the book doesn’t contain many things that would surely offend today, but his sympathies were unquestionably engaged.

Here, in an early illustration, we see the brave and beautiful “Jewess” about to prove her mettle by jumping from a turret to avoid a fate worse than death.

I shan’t sport with your intelligence by telling you any more about the plot. You’ll have to read it for yourself, or at least watch the movie with Robert Taylor, Joan Fontaine, and Elizabeth Taylor (though I hear that varies quite a bit from the book).

I must say though, it is refreshing to read a book written when literary devices such as characters remaining unrecognized by their own families while wearing ridiculously flimsy disguises were still relatively fresh. The essay at the beginning of my edition (which I only read as an after thought, to confirm my own surprise at the book’s unexpected overtones) also credits Scott with providing inspiration for the Ku Klux Klan via the scene of Rebecca’s trial by the white-robed Grand Master of the Templars. Oops. I guess I revealed a bit more.

Ivanhoe, kneeling before his childhood sweetheart (an utterly insipid, perfectly blond Saxon damsel) is completely unknown, thanks to his funny hat.

Now go get your own copy of Ivanhoe, or borrow mine if you like. Make a bowl of popcorn, find a pleasant chair, light a few extra candles, and enjoy.

Once again it’s a pleasure to read one of your essays and it may just make me go and get a copy of Ivanhoe.

[…] Which isn’t to say that I am actually related to Scottish nobility. We probably came from the poor-relation branch of the family. But I think it is fair to say that I am descended from the same Gray (Grey) who accompanied the Normal conqueror. Why do I suddenly have even less sympathy for Ivanhoe? […]

[…] Ivanhoe, by Sir Walter Scott […]