Sonatina

May 21st, 2012

I love musical terminology. It’s all so, well musical. Or perhaps Italian is simply a lyrical language. Which leads one to wonder how they happened to choose Italian for musical notation. But that’s another story altogether.

I’ve been re-learning Clementi’s Sonatinas lately and, while trying to master a particularly thorny bit of fingering, began to wonder whether the sonatina form had any particular characteristics. Turns out, sonatina simply means a little sonata. (Sonata being a piece of music that is played, not sung, derived from the Latin sonare, “to sound” — thank you Wikipedia).

Unlike a sonnet (I’ve been reading Edna St. Vincent Millay), or even a sonata, the sonatina has no formal requirements of form. It’s just a collection of movements, unspecified in number, character, or arrangement, and is too short or too simple to make a fully formed sonata.

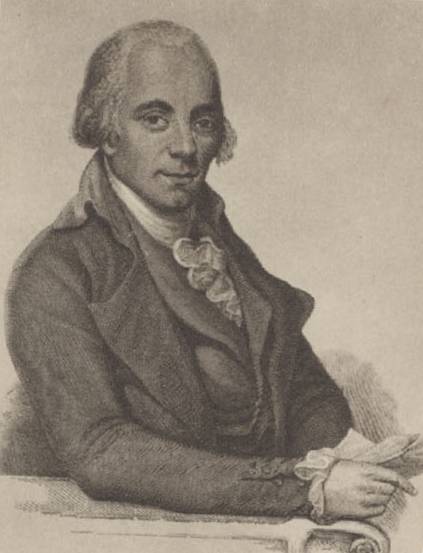

Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) was a prolific Italian composer and noted pedagogue. He wrote a series of sonatinas for his piano students in 1797 and I am testament to the fact that they were still in use 200 years later when I was winding up my own stint as a piano student. You can learn more about the “father of the pianoforte” from the Clementi Society.

I can’t resist sharing the following excerpt from the introduction to my “Schirmer’s Library” edition of Clementi’s Sonatinas. It was written by Philip Hale in 1893 and is a good argument for writing your own biographical blurb now if you intend to be posthumously published.

“The career of Clementi was remarkably free from the adventures, the disappointments, the reverses, that are so often connected with the artistic life. It was so free from romance that the biographers of the last century felt obliged to invent incidents of passion. He was a favorite in society, for his manners were elegant, and he was always a cheerful and entertaining companion. He enjoyed a game of billiards, but he was frugal in his habits. He was exceedingly fond of money, and many amusing stories are told of his stinginess. He was industrious, and often gave fifteen hour-lessons a day at a guinea a lesson. It is unnecessary to add that by teaching, playing, composing, improvements in the pianoforte, and a diligent pursuit of business, he was able to leave a large fortune.”

Oh my.