HSF #3: Under it All

May 14th, 2013

Boy is this a belated post. The deadline for this challenge was February 11. That’s MONTHS ago. Oops. But here it is in the spirit of better late than never (when you try to juggle as many things as I do, this becomes one of your favorite phrases)…

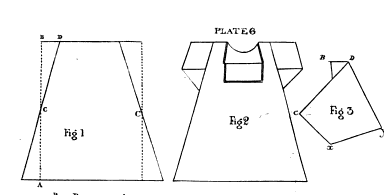

I made a early-mid-19th century shift exactly by the book. That is, following the directions in the Workwoman’s Guide (1838) to the letter. I mostly used the written directions and measurement charts, but it’s nice to have illustrations for reference as well, like plate 6, shown here. Don’t worry if you can’t find the illustrations when you read the Guide on Google Books — they’re all at the end.

After a little hesitating, I decided to break into my stash of NYC linen. I selected a piece with a fairly loose weave — not at all historically accurate, especially since the warp is made of much tinier threads, throwing the balance completely off. But it seemed like the best approximation of the “stout linen” recommended for shifts “for poor children.” (I realize that makes no sense at the moment, but I’ll explain what I’m working on eventually.)

The fabric was 60 inches wide, give or take a few after I shrunk it twice, so I was able to cut it in half and scrape out enough to make two shifts in the “first size” (aka smallest) with a single length. I cut it “to a thread,” which is the laborious process of pulling out a thread and cutting along the empty line to make sure you stay on grain — alas, linen cannot be torn like cotton. Then folded my length of fabric at the shoulder and basted up the selvedges so they’d stay together as I cut off the gores (see figure 1).

I was reminded how tricky gussets can be when you’re sewing and felling. I’ll admit here that I completely messed up the first sleeve. A quick refresher from a selection of mid-19th century sewing manuals helped me get the second sleeve nearly perfect.

Once I’d cut out all the pieces — which was pretty easy since they were just rectangles — it went together very quickly. The edges were simply hemmed, with the exception of the neckline, which got double-turned and sewn for extra strength.

I forced myself to mark the shift at the back neckline with red embroidery thread. Workwoman’s Guide doesn’t mention ink in its section on marking, so I gritted my teeth and made with the magnifying glass. I opted for only my initials since using the current year would look funny, and it didn’t feel right to lie about the year either. I mean, with all that hand-sewing and accurate construction, it might get mistaken for an antique, right?

I was a little nervous about making the smallest size. I mean, I may be fairly trim for a 21st, century person, but I’m also half a foot taller than the average woman of 1850 and probably have a bigger — or at least longer — bone structure overall. I did end up adding 4 inches to the length, figuring that’s about how much extra length is in the part of my body covered by the shift. To my surprise, the shift is actually quite roomy. With the exception of the sleeves, which JUST fit my not-particularly-muscular upper arms.

The neckline is especially large. At first I thought I’d made a mistake. But my measurements were perfect. And then I thought there might be a drawstring coming later on in the directions. But nix on that as well. So I am left with three possibilities.

- Women in the mid-19th century were universally better endowed than myself (which isn’t surprising considering what I’ve noticed in the early 21st century).

- They made all their clothes really big because repeated washday boilings were bound to shrink them considerably.

- It’s time to reevaluate the way I interpret “fit” of historic undergarments.

Number 3, while it may seem unlikely, and definitely involves eating at least a sliver of humble pie, does fit with my experience recreating the Regency apron-front dress from Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion I. It’s also supported by some of the paintings I’ve been working from for my latest project. And here I thought the artists were being salacious by portraying women with their shifts falling off their shoulders. But maybe they just slipped on their own…

Just the facts, Ma’am: Workwoman’s Guide Shift

The Challenge: #3: Under It All

Fabric: 60″ wide hopelessly modern linen with an unbalanced weave

Pattern: From the written directions and diagrams in the Workwoman’s Guide, 1838

Year: 1838 (this shape remains accurate through the mid 1850s)

Notions: 100% cotton thread, red cotton embroidery floss

How historically accurate is it? I’ll give it 95%. It’s entirely hand-sewn according to mid-19th century plain sewing directions, with attention to specific techniques for shift necklines and gussets from the Workwoman’s Guide and other sources. The construction is as accurate as possible given the width and weave of the modern fabric I had to work with. Because of the fabric, I had to sew and fell the gores onto the bottom of the shift body, whereas if I’d been using proper fabric, I would have sewn them selvedge to selvedge. This time I broke out my 100% cotton thread, along with the beeswax and lots of extra patience.

Hours to complete: Probably about 15. It’s hard to tell when you sew in odd moments, like before breakfast, or while you’re playing dummy at the bridge table…

First worn: This afternoon, to take pictures. It will ultimately figure in a much larger project that is currently stamped TOP SECRET (mostly because I love being dramatic).

Total cost: About $10. I don’t remember exactly how much I paid for the linen, but it was probably about $7 a yard. The cotton thread wasn’t cheap, but I barely made a dent in the spool.

HSF #2: UFO

January 28th, 2013

No, I didn’t sew an alien. In costumer slang, UFO stands for “unfinished object.” And like most historically inclined seamstresses, I’ve got plenty of those laying around. As of tonight though, there’s one less.

That’s right, it’s a petticoat. I’m predictable. Deal with it.

I actually sewed this petticoat a couple years ago. And it’s far from perfect. There’s the whole hem pretending to be a tuck issue. Plus the other two depressingly small and poorly placed tucks. It’s also a little on the short side. Last but not least, it was (until yesterday) missing a waistband.

Just as I learned from the mixed up hem on this petticoat (my next petticoat had 6 generous tucks and a proper hem), I also took a few pointers from a previous petticoat waistband. Before, I used a strip of the same cotton as the petticoat itself. It worked okay, but felt a bit flimsy. I also had to reinforce the area where I sewed the buttons. This time, I decided to borrow a trick I’ve seen on a few extent mid-19th century petticoats and make my waistband out of closely woven linen. Truth be told, I simply cut off the wide hem of an old tablecloth, folded the cut edges in, and whipped it closed. Voila! Perfect linen petticoat band.

Just the facts, Ma’am: Previously unfinished mid-19th century petticoat

The Challenge: #2: UFO

Fabric: 45″ wide cotton muslin (calico), the edge of a linen tablecloth

Pattern: Based on mid-19th century directions and extant garments

Year: 1855 (that’s the year the lace pattern was published in Peterson’s)

Notions: 2 mother of pearl pressed buttons, 135 inches of cotton lace

How historically accurate is it? Let’s say 90%. It’s entirely hand-sewn, with hand-crocheted lace from an 1855 pattern. The construction (minus the hem and tuck issues) is pretty much accurate. I used polyester thread. And the buttons are kinda wrong. They should be milk glass or thread probably.

Hours to complete: Who knows at this point! The lace alone took weeks. The petticoat itself is fairly simple, so probably took under 10 hours. Setting the waistband added another 4 or 5.

First worn: Not yet, not for a while. Still need to make that pesky cage. Which, it turns out, can’t be made until I redo my corset. And you wonder why I’ve got a studio littered with “ufo’s”

Total cost: About $15, counting the muslin and the cotton thread. The buttons were a gift from mom and dad way back in my teens (they gave me a huge bag full from a company that operates an antique button press — more accurate for late Victorian/Edwardian). I don’t recall where I got the cannibalized tablecloth.

HSF #1: Bi/Tri/Quadri/Quin/Sex/Septi/Octo/Nona/Centennia

January 13th, 2013

I wasn’t sure I was even going to participate in the first official Historical Sew Fortnightly challenge. To be honest, I don’t really have an affinity for any years ending in 13. Most of my historical fashion obsessions seem to spring from the historic houses at which I have worked. Turn of the century, yes — I’ve done Edwardian and Federal/Regency/Empire — but I’ve never made it into the teens.

It was a 1913 cutting diagram from the introductory materials in Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion II that finally sold me. A description on Dressmaking Research caught my eye, and seemed to jive with the Arnold diagram.

“Skirts cut in two pieces have proved so well liked that they are one of the most often remarked models in the suit or separate skirt. No. 6658 is the newest design with just the desired width. The possibility of sloping the front edges away at the foot is appreciated, for some women like the added freedom it allows in walking. In the medium size the lower edge measures about one and five-eighth yards. There is a slightly high or a regulation waistline fitted with scant gathers or darts. The skirt may be closed at back or front and finished in round or shorter length. Serge, cheviot, wool rep, whip-cord, broadcloth, homespun, suitings, linen, pique and agaric are the materials suggested.

“A woman of medium size requires two and five-eighth yards of material thirty-six or more inches wide, Thirty-six inches is the narrowest width that may be successfully used because the model is cut in only two pieces.”

Designer, March 1913

So with brave heart and steady hand, I chopped into a length of green-and-white textured houndstooth of indeterminate fibre content (thrift store find) and started draping. The result is a little iffy, but not terrible for a first draft. I really like the two-piece construction: a pair of identical sections, each comprising half of the front and back, with a dart over the side hip and darts or gathers fitting the waist. It lends itself beautifully to the pegged tops, draping, and cross-overs that were popular in the teens. It’s also just fine as a plain walking skirt.

Unfortunately, a couple of late night cutting mistakes combined with fabric that refused to dart properly (wool will work MUCH better) add up to a skirt that doesn’t quite scream 1913. But it passes. With my second armistice blouse, plus 1930s hat and gloves thrown in, it’s surprisingly credible. Especially since I haven’t a stitch of teens underwear to help with the shaping.

Notice the wrinkles and flabbiness around the hem? They wouldn’t iron out, no matter how long and hard I pressed, nor how many vile chemical smells emanated from the heated fabric.

Here you can see my dirty little secret — the majority of the skirt’s fullness ended up in the back. These gathers are a little more than scant — shades of Edwardianism, gasp! But I think I can fix it next time by moving the side darts and using more conducive fabric. Can you tell I’m eager to explore this pattern more? And maybe even create a modern version to accompany my updated armistice blouses…

The only part of this skirt that really makes me happy is the waistband.

It provided one of those costuming “ah ha” moments when you suddenly realize that you’ve created something that looks just like a technique seen on extant garments but never properly understood. Lots of late-19th and early-20th century skirts have self-fabric waistbands faced with grosgrain ribbon. It’s a neat trick, creating a strong band without too much bulk. Common sense told me to sew the skirt to the ribbon first. Then I machine-stitched the fabric waistband to cover the join, turned the top and side edges under, and blind-stitched it to the ribbon. The result mimics period waistbands perfectly, right down to the line of machine stitching along the bottom of the ribbon!

Just the facts, Ma’am: 1913 Two-Piece Skirt

The Challenge: #1: Bi/Tri/Quadri/Quin/Sex/Septi/Octo/Nona/Centennia

Fabric: Textured Green & White Houndstooth, unknown fibre content (thrift store find)

Pattern: Custom draped based on cutting diagram in Patterns of Fashion II

Year: 1913

Notions:5 metal snaps, two waistband hooks and metal eyes.

How historically accurate is it?Hardly. Let’s call it more historically inspired. The silhouette is close-ish in a generic sense, but definitely no cigar. I need to do a LOT more research (and make some underwear) before I can feel confident calling anything I make from the teens historically accurate. I did use all period techniques — no zig-zag stitch, plenty of hand-finishing, etc. The material itself is some modern abomination, but the metal closings are pretty much accurate.

Hours to complete: Less than 10. Which is probably a speed record for me! What a difference a sewing machine makes.

First worn: This afternoon, to take photos. I briefly considered taking it out for a neighborhood stroll, but a rare California cold snap kept me huddled indoors. Thanks to a teensy cutting mistake (where I ignored seam allowances at the center front), I probably won’t be wearing this very often until the approach of bikini season inspires me to lose a little weight.

Total cost: $2.5o for thrift store fabric. The fasteners were inherited.

HSF #0: Starting Simple

January 2nd, 2013

New year, new petticoat. Yep, I’m still me.

Amid the holiday rush, I managed to find a few hours each day to “zen out” on handsewing. The result, a long overdue petticoat for a swath of 1850s-era “guipure” crochet edging I finished more than a year ago. Why now, you ask? What exactly motivated me to finally get this done?

It was the Historical Sew Fortnightly, organized by The Dreamstress, who is one of my very favorite bloggers even though I’ve never met her (I always feel a bit uneasy reading the blogs of people I don’t actually know — sort of like I am stalking them).

Anyways, the idea is that participants are challenged to sew an historical (pre-1938) garment every two weeks for the next year — 26 in all. Each fortnight has a theme around which to organize your project. And best of all, there’s a bustling Facebook group to share research, inspiration, and lots of delicious pictures of the completed projects! This petticoat is my contribution for challenge #0, the pre-challenge. It’s title was “Starting Simple.” Make something fairly easy, and/or something that you’ve made before.

It’s a basic mid-19th century style top-layer petticoat. I used three breadths of 45 inch cotton, sewn up the selvedges and cartridge pleated to a buttoned waistband. Based on this gorgeous example from The Metropolitan Museum, I decided to include 6 tucks above the edging.

As is obvious from the picture of my deflated petticoat at the top of this post, I still need to put my cage crinoline together. I blush to admit I was in such a hurry to finish this, I committed the curatorial sin of using an extant cage crinoline (circa 1860-1865) from my personal collection to balance the petticoat. But I did resist the urge to get it out again for the photograph. I was also too lazy to put on my corset to figure out where to sew the buttons…

Just the facts, Ma’am:

The Challenge: #0 Starting Simple

Fabric: Cotton muslin

Pattern: Based on period directions and extant garments

Year: 1850-56

Notions: 2 mother-of-pearl buttons (I need to learn to make thread buttons!)

How historically accurate is it?About 90%. It’s impossible to get completely accurate materials — for example, the quality and size of the cotton are a little off, and I have a feeling the thread I used for the crocheted edging is the wrong size (it was the right number, but seems a little on the large side). Otherwise, it’s completely hand-sewn with period plain-sewing stitches.

Hours to complete: 20-30. Thanks to those six tucks, I figure I put upwards of 1,200 inches of sewing into this petticoat. Much of it running at 18-stitches-to-the-inch…

First worn: Not for a while yet — I need to finish the cage and/or crinoline, not to mention a whole bunch of other pieces to complete my 1850s wardrobe. This petticoat, along with others, will eventually be part of a mixed-media art exhibit as well.

Total cost: Counting fabric and crochet thread, about $15.