Sonatina

May 21st, 2012

I love musical terminology. It’s all so, well musical. Or perhaps Italian is simply a lyrical language. Which leads one to wonder how they happened to choose Italian for musical notation. But that’s another story altogether.

I’ve been re-learning Clementi’s Sonatinas lately and, while trying to master a particularly thorny bit of fingering, began to wonder whether the sonatina form had any particular characteristics. Turns out, sonatina simply means a little sonata. (Sonata being a piece of music that is played, not sung, derived from the Latin sonare, “to sound” — thank you Wikipedia).

Unlike a sonnet (I’ve been reading Edna St. Vincent Millay), or even a sonata, the sonatina has no formal requirements of form. It’s just a collection of movements, unspecified in number, character, or arrangement, and is too short or too simple to make a fully formed sonata.

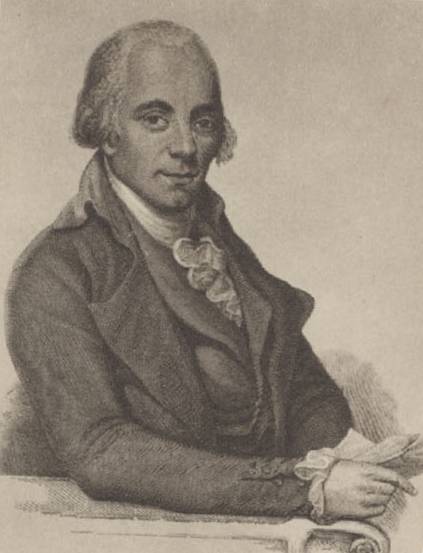

Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) was a prolific Italian composer and noted pedagogue. He wrote a series of sonatinas for his piano students in 1797 and I am testament to the fact that they were still in use 200 years later when I was winding up my own stint as a piano student. You can learn more about the “father of the pianoforte” from the Clementi Society.

I can’t resist sharing the following excerpt from the introduction to my “Schirmer’s Library” edition of Clementi’s Sonatinas. It was written by Philip Hale in 1893 and is a good argument for writing your own biographical blurb now if you intend to be posthumously published.

“The career of Clementi was remarkably free from the adventures, the disappointments, the reverses, that are so often connected with the artistic life. It was so free from romance that the biographers of the last century felt obliged to invent incidents of passion. He was a favorite in society, for his manners were elegant, and he was always a cheerful and entertaining companion. He enjoyed a game of billiards, but he was frugal in his habits. He was exceedingly fond of money, and many amusing stories are told of his stinginess. He was industrious, and often gave fifteen hour-lessons a day at a guinea a lesson. It is unnecessary to add that by teaching, playing, composing, improvements in the pianoforte, and a diligent pursuit of business, he was able to leave a large fortune.”

Oh my.

Waltzing Away

May 3rd, 2012

Our new house came with a beautiful (and very special as it belonged to one of our dear friends) baby grand piano on long-term loan. It’s been more than a decade since I’ve lived with a piano, and I had no idea how much I missed having one around!

I guess I’ve got waltzes on my mind. In between practicing “Merry Widow Waltz” for the upcoming show, I’ve been reacquainting myself with songs learnt in piano lessons of yore. Including my favorite by Chopin, his Grande Valse Brillante.

Turns out it was written in 1833 and published in 1834 by the prolific Polish composer. I started learning it in the early1990s, and will probably never play it very well. Especially the movement with all the little grace notes…

Here, mostly to satisfy your insatiable curiosity, o best beloveds, is a recording I made this morning of the first two movements, mistakes and all.

There’s just something wonderful about a waltz!

Brignal Ballad

September 9th, 2011

It’s always a good day when you discover a new song, especially one published in 1829, with words by Sir Walter Scott and arrangement for voice and piano by J. F. Hance!

O Brignal Banks Are Wild and Fair: a Scotch Song

O Brignal Banks are wild and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

And you may gather garlands there,

Would grace a summer queen.

And as I rode by Dalton hall,

Beneath the turret high,

A maiden on the castle wall

Was singing singing merrily.

“O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green,

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.”O Brignal banks are fresh and fair,

And Greta woods are green.

I’d rather range with Edmund there;

Than reign our English Queen.If maiden, though wouldst wend with me,

To leave both tow’r and town,

Thou first must guess what life lead we,

That dwell by dale and down.

And if thou canst that riddle read,

As read full well you may,

Then to the greenwood shalt though speed,

As blithe as queen of May.

Yet sung she “Brignal banks are fair,

And Greta woods are green;

I’d rather range with Edmund there,

Than reign our English queen.”

I found scans of the folio, published in New York by Dubois & Stodart, on this website.

I’ll wager you already know who Sir Walter Scott is, and perhaps have even read some of his work. I prefer his poetry (it seems to wear its two-centuries a bit better), though to be fair, I’ve only read one Scott novel. Here is the Baronet (made 1818) himself in an 1822 portrait by Raeburn. He appeals to the Scott in me.

But odds are you haven’t got the faintest idea who J. F. Hance is. Neither did I until last year. It turns out Mr. Hance was an American composer, active during the early Romantic period, right about the same time as Sir Walter Scott. History has obscured most of his works, and perhaps deservedly so. He is listed as an “arranger” on this piece, though there is no evidence that anyone else wrote the tune. Perhaps it’s a Scottish folk song that he kitted up for the piano forte? It’s quite pretty actually, unlike many of the things that Hance did take credit for writing…

I first ran into J. F. Hance at the museum where I work. A book of piano lessons was found in the collection, owned by the family who once lived in the house. It’s an obscure pedagogical work called Instruction in the Attainment of the Art of Playing the Piano Forte, comprising lessons in basic music theory, 15 rather quixotic etudes, and two mediocre songs. The author is none other than J. F. Hance. In spring 2010, I reproduced the book (hours of wrangling with Photoshop and rendering in Illustrator to get printable page images). The etudes and songs were then recorded on the museum’s recently restored 1840s rosewood piano forte. This instrument, also owned by the family, still sits in the same parlor where it’s been since the mid-19th century. And it’s almost certain that the pieces in the Hance book were played on it by the daughters!

Thrill of thrills, after many attempts to find a more accomplished musician, I ended up playing for the recording. It makes sense in a way, since the women who played the piano when it was new were certainly not professionals. I’ll never forget the feel of the keys, or the sound of the notes echoing through the room. In some ways, it’s as close as we’ll ever come to hearing what they heard, so many years ago. Same room. Same piano. Same song.

Following the advice of our excellent conservator, we decided not to continue playing the piano at the museum. It’s simply too fragile, and continued use means that the original parts will eventually have to be replaced by modern fabrications. This instrument is too much in tact, too well-provenanced, too rare. They do play the recording for visitors though, and soon it will be available for purchase on CD.