HSF #2: UFO

January 28th, 2013

No, I didn’t sew an alien. In costumer slang, UFO stands for “unfinished object.” And like most historically inclined seamstresses, I’ve got plenty of those laying around. As of tonight though, there’s one less.

That’s right, it’s a petticoat. I’m predictable. Deal with it.

I actually sewed this petticoat a couple years ago. And it’s far from perfect. There’s the whole hem pretending to be a tuck issue. Plus the other two depressingly small and poorly placed tucks. It’s also a little on the short side. Last but not least, it was (until yesterday) missing a waistband.

Just as I learned from the mixed up hem on this petticoat (my next petticoat had 6 generous tucks and a proper hem), I also took a few pointers from a previous petticoat waistband. Before, I used a strip of the same cotton as the petticoat itself. It worked okay, but felt a bit flimsy. I also had to reinforce the area where I sewed the buttons. This time, I decided to borrow a trick I’ve seen on a few extent mid-19th century petticoats and make my waistband out of closely woven linen. Truth be told, I simply cut off the wide hem of an old tablecloth, folded the cut edges in, and whipped it closed. Voila! Perfect linen petticoat band.

Just the facts, Ma’am: Previously unfinished mid-19th century petticoat

The Challenge: #2: UFO

Fabric: 45″ wide cotton muslin (calico), the edge of a linen tablecloth

Pattern: Based on mid-19th century directions and extant garments

Year: 1855 (that’s the year the lace pattern was published in Peterson’s)

Notions: 2 mother of pearl pressed buttons, 135 inches of cotton lace

How historically accurate is it? Let’s say 90%. It’s entirely hand-sewn, with hand-crocheted lace from an 1855 pattern. The construction (minus the hem and tuck issues) is pretty much accurate. I used polyester thread. And the buttons are kinda wrong. They should be milk glass or thread probably.

Hours to complete: Who knows at this point! The lace alone took weeks. The petticoat itself is fairly simple, so probably took under 10 hours. Setting the waistband added another 4 or 5.

First worn: Not yet, not for a while. Still need to make that pesky cage. Which, it turns out, can’t be made until I redo my corset. And you wonder why I’ve got a studio littered with “ufo’s”

Total cost: About $15, counting the muslin and the cotton thread. The buttons were a gift from mom and dad way back in my teens (they gave me a huge bag full from a company that operates an antique button press — more accurate for late Victorian/Edwardian). I don’t recall where I got the cannibalized tablecloth.

Scholarship Surfaces

July 25th, 2012

Remember that “shocking” finding at Innsbruck I wrote about last week that seemed to disprove everything anyone had ever believed about Medieval underwear? BBC History Magazine has posted a non-sensationalized article about it, complete with comments by the costume historian who is researching the finds. Well done! And well done Katy of “The Fashion Historian” for sharing it with the rest of us.

Here is a link to the new article.

I had plans to create another post featuring the second picture that’s been going around, explaining how this “string-bikini bottom” might very well be similar to garments described by 19th-century health manuals, to be worn by menstruating women, but that is well covered by Ms. Nutz, the textile historian quoted in the above article. So I will desist.

Really, Really Old Underwear

July 17th, 2012

My fascinating friend, and 19th-century warrioress extraordinaire, Rachel posted a link to this article about a recent discovery by the archaeology department of the University of Innsbruck. They seem to have found evidence of hitherto unknown forms of fifteenth-century undergarments in an Austrian castle. If you’ve read any of my previous postings, you know I’m a sucker for a good historical underwear discovery.

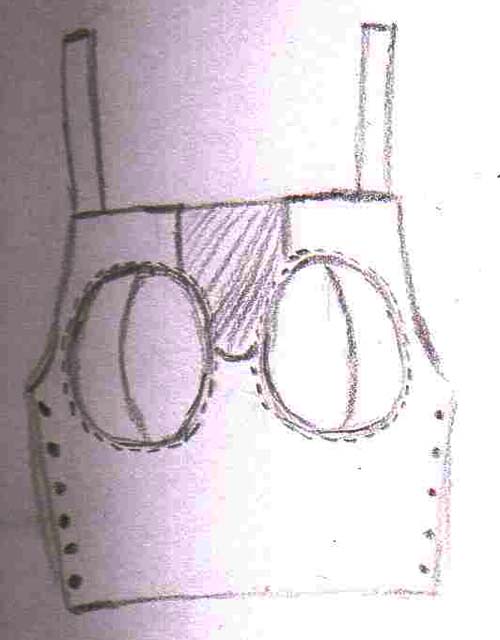

The article is a little misleading however, as it doesn’t point out that this brassiere look-a-like is actually missing a large chunk of material that would have covered the stomach from breasts to waist, and likely a back portion that laced on at the sides and anchored the other end of the shoulder straps. See the piece with lacing eyelets hanging down the left side? It probably survived because it was reinforced.

Here’s my hastily drawn rendering of what it might look like with the missing material.

I’m undecided about what’s going on between the breast cups at the top. Is it purposefully left open because fifteenth-century German underdresses (worn over underwear, but under the overdress) often had deep V necks? Or was there a different, finer, or even decorative fabric inserted there? The top edge looks like it was meant to end where it does, but it may also just be impossible to see in the picture that it’s also ripped and the same material once ran all the way across.

I also wonder how much of a revelation this actually is. I’m incredibly ignorant about fifteenth-century Germanic fashion, so I looked it up in “A History of Costume” by Carl Köhler, a 19th-century costume historian. In the section on fifteenth-century German women’s dress, he tells us:

“A chronicler of the day describes this fashion [a new form of dress in the late 1400s) thus: ‘Girls and women wore beautiful wimples, with a broad hem in front, embroidered with silk, pearls, or tinsel, and their underclothing had pouches into which they put their breasts. Nothing like it had ever been seen before.’ “

Hmmmm. But, as I said, I know next to nothing about this period. So I am happy to take the word of those who do that this is a remarkable discovery. There’s another garment featured in the article, and I also have a few ideas about that. But I’ll save them for another post.

In the meantime, if you run across a more scholarly treatment of this topic, please let me know. I’d be anxious to hear some of the finer points describing the findings and why they are so surprising.

Back to the Drawing Board

July 11th, 2012

After a night of solid stitching, much of it by hand (slip-stitched faux french seams, triple-basted and back-stitched bust cups), I was finally ready for the pre-strap and closure fitting of my experimental bodiced petticoat. With the center front pinned neatly together, I stood in front of the mirror and my heart sank. By the time I’d piped and bound the bust cup seams, they were nearly as bulky as an underwire. And it was quite clear that the front closure needed boning, possibly the side seams as well. There was no way the final result would even be as comfortable as a modern brassiere. Which defeats the whole point.

Back-stitching the bulky bust cup seam

So I went back to my books in search of another solution to the underwear problem. I’m aiming for a wardrobe of clothing based on styles popular from about 1900 to 1940. So it seemed logical to look for undergarments from those eras. Chemise with slash and gather bust shaping (I’ve seen one in an historic collection), bust bodice, bandeaux, and/or…

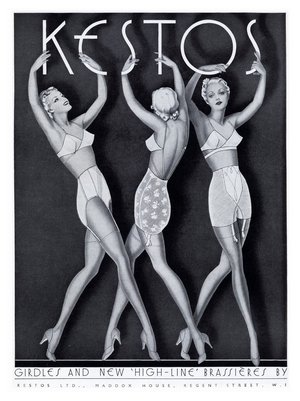

That’s right, a Kestos. Named for Aphrodite’s own support garment, the Kestos was the most popular brassiere of the 1930s. And it was originally designed with a pair of folded linen handkerchiefs connected by elastic and ribbons! What could be more comfortable? Or better suited to my free-form wardrobe?

I think I may also experiment with a few chemise configurations, given my obsession with the chemise form in general. It seems like a useful undergarment for many of the looser styles I have in mind. Petticoats will just have to be separate, which is perhaps more convenient for washing anyways.

Re-imagined Underwear

July 6th, 2012

I must have particularly bony knees, or kneel more than I realize; within the past six months, nearly all of my jeans have developed holes. Rather than buying another round of denim, I’ve decided to take the opportunity to make a drastic change in my wardrobe.

As any aspiring fashion historian knows, it’s the undergarments that make the clothes. So I will begin by re-imagining my underwear.

Ankle-length skirts will definitely be a staple of my new wardrobe, so I’ll need a petticoat or two to give them shape. And speaking of support, I’m even more anxious to abandon my brassieres than I am to ditch my jeans. So I decided on a bodiced petticoat to offer exterior support below and interior support above. The inset bust cup is cut on the bias and lightly pleated across the top. It’s surprisingly effective.

While the blush-colored cotton for my first petticoat tumbles around the dryer, I cut bias strips from an old cotton shirt. I’ll use them to bind the bodice and straps, and perhaps to pipe the seam under the bust.

Older Posts »