Practical Instructions in Stay Making

December 8th, 2010

These are posted verbatim from the August 1857 (not 1858, as I had previously thought) issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, with gratitude to Accessible Archives for making them so, well, accessible.

PRACTICAL INSTRUCTIONS IN STAY MAKING.

Materials necessary for making a Pair of Stays .— Half a yard of material; a piece of stay-tape for casing; some whalebone, either ready prepared, or in strips to be split and shaved to size; a steel busk; wash-leather sufficient to cover it, and webbing to case it; a paper of 8-between needles; a reel of 28-cotton; a box of French holes; and a punch for putting them in.

DIRECTIONS FOR TAKING THE MEASURE.

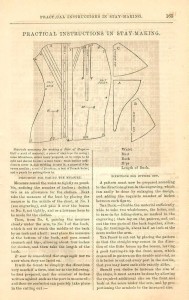

Measure round the waist as tightly as possible, noticing the number of inches; deduct two as an allowance for the clothes. Next take the measure of the bust by placing the measure in the middle of the chest, at No. 1 (see engraving), and pass it over the bosom to No. 8, not tightly, and no allowance here to be made for the clothes. Then, from No. 8, passing the measure closely under the arm, to No. 1 of the back, which is not to reach the middle of the back by an inch and a half; next place the measure at the bottom of the busk, and pass round stomach and hips, allowing about four inches for clothes, and then take the length of the Lusk. It must be remembered that stays ought NOT TO MEET when they are laced on. It will be found to simplify the directions very much if a form, similar to the following, be first prepared, and the number of inches written against each as the part is measured; and then no confusion can possibly take place in the cutting out :— Waist Bust Back Hips Length of Busk.

DIRECTIONS FOR CUTTING OUT.

A pattern must now be prepared according to the directions given in the engraving, which can easily be done by enlarging the design, and adding the requisite number of ‘inches between each figure. THE BACK.— Double the material sufficiently wide to take two whalebones, the holes, and to turn-in for felling-down, as marked in the engraving; then lay on the pattern , and cut out the two parts of the back together, allowing, for turnings-in, about half an inch at the seam under the arm. THE FRONT is cut out by placing the pattern so that the straight way comes in the direction of the little bones up the bosom, leaving a good turning-in up the front seam, which crease off in pattern on the double material, as it is better to cut out every part in the double, that you may have each side exactly alike. Should you desire to increase the size of the stays , it must ALWAYS be done by allowing the required additional size on the front and back at the seam under the arm, and by proportioning the armhole to the increased size. When the bosom gores are to be put in, the material is merely cut from No. 2 to No. 3, and from No. 5 to No. 6, in a direct line, cutting none away. In cutting places for stomach and hip-gores, in front and back, cut straight up, and then from No. 7 to No. 8 in back, and from No. 13 to No. 14 in front. Then cut out all the gores, as directed in the engraving.

DIRECTIONS FOR MAKING.

1st.— Stitch a place for the first bone at back, and for the holes, the width of half an inch, keeping the line perfectly even, and fell down a place for the second bone on the wrong side. 2d.— Fit the bosom-gores by making a narrow turning-in from No. 2 to No. 3, and from No. 3 to No. 4; fix the gore at 3, the straight side of the gore next the busk, tacking it very closely up to No. 2; then fix the other gore in like manner at No. 6, the straight side next the armhole, tacking up to No. 7. 3d.— With a measure, make the required size across the bust, by increasing or diminishing the gores at the top; tack the other sides very firmly from No. 3 to No. 4, and from No. 6 to No. 5, shaping them prettily, narrow at the bottom, and of a rounded form towards the top; then stitch them very neatly; and, cutting away superfluous stuff on the wrong side, hem down, beginning each side from No. 3 to No. 6. 4th.— Hem a piece of stay-tape at the back, for little bones, and stitch down the middle of it on the right side. The other half front to be done in a similar in manner. 5th.— Put in the stomach-gores, turning in from 14 to 15, and tacking the straight side of the gore under it; and fix the hip-gores in the back in like manner, the straight side to the holes. 6th.— Join the seams under the arm by pinning No. 10 of half-front to No. 11 of half-back, to half the size of waist required, wrapping the front on to the back. Everywhere face each piece to its fellow piece, and crease it, that it may be exactly the same size and shape. Then do the other half in the same way. 7th.— Having closed the seam, finish the stomach and hip-gore by measuring and making to the size required round the hip, by letting out or taking in, rounding them to fit the hip; face and crease the gores for the other half, which is to be finished in the same manner. 8th.— Take a piece of webbing wide enough to case the busk when covered with wash-leather; double it exactly, and tack down the half-front, the double edge being scrupulously down the centre of the stays ; fell it on very closely; then stitch the two halves together at the crease down the middle; turn the other half of the webbing on to the unfinished side, and fell it down as before, turning in a little piece top and bottom, and finish. 9th.— Bind the stays very neatly, top and bottom. 10th.— Put in the holes, two near each other at the top of the right side, and two near each other at the bottom of the left side— the rest at equal distances. Proceed now to the boning, which do by scraping them to fit nicely; then, having covered them with a piece of glazed calico, cut, at the bottom of each bone place, a hole, like a button-hole, and work it round like one; put the bones in, and drill a hole through the stays and the bone, about an inch and a half from the top and bottom of each bone, and fasten them in with silk by bringing the needle through the hole to the right side, and passing it over the top of the bone, as marked at No. 12. Then put in the busk; and, if a hook is required at the bottom, put that in before the husk, which is best done by leaving a short hole in the seam, and passing the hook through, fastening it securely at the back. The busk must be stitched in very firmly, top and bottom. Should the stays have become soiled in the process of making, they are easily cleaned with bread inside and out, and, when cleaned, must be nicely pressed, taking care to make no creases anywhere. If these simple directions be strictly adhered to in the making up, a pair of well-fitting stays , at a trifling cost, will reward the pains of the worker.

Insane!!!!

“THE FRONT is cut out by placing the pattern so that the straight way comes in the direction of the little bones up the bosom, leaving a good turning-in up the front seam, which crease off in pattern on the double material, as it is better to cut out every part in the double, that you may have each side exactly alike”

That’s crazy and awesome. Who ever heard of a bias-cut pair of stays?! Then again it makes sense, as it would mold to your body pretty well (at least the part without the lacings!).

I’m having one of those “why did I never think of this?” moments. 🙂

[…] and stomach-gores are all neatly hand-sewn and felled in place. I particularly like the way the directions include steps for fitting each gore as they are first basted in, then adjusted, and finally sewn in […]

[…] made another exciting discovery about the stay pattern though. They are meant to be spiral laced! For those of you who aren’t corset aficionados, […]

Bias cut stays! Yay! I am working on a slightly earlier period set of bias-cut stays currently (late 1830s) and they’re so much fun. Also, so much fun to wave the mock-up at people who claim that corsets are inevitably painful tools of oppression by the patriarchy. My comfy stretchy-waisted corset begs to disagree…

After helping a bunch of people fit corsets recently, several of which had bias-cut panels and gussets/gores, I’ve also realized that when you do this style of corset, it inevitably ends up fitting so that the back lacing edges get cut crooked – completely off-grain, so they curve in at the waist. It’s mind-boggling – but makes perfect sense when you look at the WWG illustration, or closely at originals. Corsetry: an ongoing adventure.

I must own myself quite ignorant of 1830s stays (aside from having read the Workwoman’s Guide entry on staymaking), but am eager to see pictures of yours! I was excited to read about your custom-made wooden busk. I’m currently in search of someone to make a custom steel busk for my “real” stays.

What’s so weird about the 1855 pattern is that it’s nearly the same as the standard Civil War era corset that everyone makes, at least in basic shape. But then it has all these little throw-backs to the earlier (1830s/40s) style: bias cut front (back is on the straight grain here, so perhaps not quite as stretchy as yours), solid busk, spiral lacing.

I’m definitely looking forward to feeling how it wears!

A pattern must now be prepared according to the directions given in the engraving, which can easily be done by enlarging the design, and adding the requisite number of ‘inches between each figure.

My questions is, what is the scale used to enlarge the pattern? It may be my lack of experience with historical patterns, but I’m not seeing a measurement on any of the lines to start with or a scale/ruler.

Hi Daria,

Alas, there is generally no scale given for pattern diagrams of this era. I’m not sure when the scale ruler systems and such came in, but I want to say 1860s or 70s (I read an article on it years ago, but forgot specifics). I’ve since discovered that this diagram and the accompanying instructions were taken wholesale from another magazine (I think it may have been Peterson’s) and were originally printed a couple years earlier than 1857!

Since the only two measurements in a pair of stays that are actually based on your body are the waist and the overall length at front, back, and under the arms, I just adapted the pattern to my own shape, using the diagram as a rough guide. When we first started working on this pattern, one of my friends blew up the pattern on the copier at her office, but it turns out to be really out of proportion with any normally shaped human. It took a lot of trial and error, but by setting a waist measurement (my desired corseted waist measurement, minus 3 or 4 inches for “spring”) and a center front and back measurements based on extant garments, I eventually got there.

Believe it or not, I still haven’t made my final version. Got hung up moving across country and adapting to an area where the 1850s were pretty much lawless wilderness…this is a good reminder I need to start work again on this. I’d love to see your version if you’re making one.

Thank you so much for the info and encouragement. I was already thinking of drafting a pattern to my own measurements but wanting to check in on this.

Again, thank you.

I thought I was ready to start drafting my pattern but I keep getting stuck. Here is where I’m “stuck”

gores and your measurements

chest measurement – is this taken across the fullest part of the chest while wearing a bra or is the chest measurement your chest circumference (36, 38 etc) and the gores make up the additional inches of your cup size?

What about the hip gores? Do you subtract several inches from your hip measurement and use this amount to to determine the size of your gores?

Or are the gores merely a decorative feature of the corset?

Ah, yes. The gores are indeed tricky. Alas, they are not at all decorative. Think of it like this — you’ve got a basically tubular shape (your torso) with random spherical protrusions (your breasts and hips). The body of this corset is a graduated tube shape (sloping gradually in at the middle and out again at the top and the bottom). But it doesn’t have enough flexibility as a simple tube to accommodate hips and breasts — in eras past, it simply condensed them into the tube (think Elizabethan). But in the mid-19th century, you want to emphasize the whole hour-glass thing. So you slash the fabric of the basic tube to allow your hips and breasts to poke through, then insert gores to cover them up.

If you’re working with a dress form, fitting the gores should be fairly easy. Just make up the front and back pieces in some heavy duty scrap fabric, using your waist measurement, and desired back and front lengths, and a bit of common sense so that they look reasonably like the pictures in the diagram. Baste them together, and figure out where the slits need to be to let your curves come through. Slash them about an inch deeper than they actually need to be. Insert a piece of material underneath and spread the slash until you like the fit (it’s okay to add a little more room than you actually need — you don’t want the bust or the hips to be terribly tight). Then use a pencil to trace the lines of your slash on the material underneath. Take it all off, and you’ll have the shape of your gores nicely recorded.

I went through a few adjustments on the size of my gores to get them right. And even now I’m not completely happy. They compress my bust a little more than planned, and I need to make the hip gores bigger because they are wrinkling. Obviously there are plenty of stays/corset patterns without gores/gussets. By the late 1850s you had the french style corsets which are fitted with a bunch of shaped pieces that nip in at the waist and flare out at top and bottom. They accomplish the same shape basically, though the end effect is probably a little smoother, and not quite as supportive if you happen to be well endowed.

P.S. Don’t wear a bra when you measure or fit your corset!