Free Reading

April 2nd, 2011

I’d like to make you an unusual offer. Since my garret is very small, I can’t afford to keep many books around; I generally donate my books back to Housing Works when I’m through with them (excepting the 100-or-so carefully-chosen permanent occupants of our tiny library).

But today I had a new idea. The three books pictured here have all been featured on Circa 1850 (see the links below if you are curious enough to read what I wrote about each). I would so enjoy hearing what you think of these books too. So, if you will agree to read the book, then write me a letter (or perhaps a “guest-post”) telling me what you thought, I will engage to send you any of the following:

Far From the Madding Crowd, by Thomas Hardy

Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson

To request a book, just leave a comment on this post, and I will arrange to collect your mailing address. Or, if I know you in person and you’re in the New York area, I can deliver it in person. Be quick about it though — if I don’t hear from anyone in the next week or so, I will be forced to donate the books as usual. There just isn’t room here to let them hang around too long!

P.S. While I would be tickled to send one of these to a reader overseas, I’d have to ask for a little help with postage. They’re rather weighty, and US Media Mail (which offers reduced rate for mailing books) isn’t an international option.

North & South

March 15th, 2011

No, I’m not preparing for the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War (well actually I am, but this post has nothing to do with that). North and South is the title of an 1855 novel by Elizabeth Gaskell. The titular directions refer to the north and south of England, known for manufacturing and peaceful farming respectively.

Originally published as a serial, I downloaded North and South from Google Books for free and read it on my *gasp* digital reader device. I am the first to expound on the pleasures of a well-bound book. But having neither the space nor the funds to arrange a sufficient “real” library for myself, I whispered my desire to a generous papa, and was pleased to accept his gift of a virtual book. As an added bonus, it also allows me to read rare and obscure books that I should not have been easily able to obtain in hard copy, no matter my resources.

You may wonder at my featuring two books in a row. I generally write about a book as soon as I have finished it, in hopes that the impressions created will still be fresh in my scattered brain. I finished Tess on Sunday morning, just as I came down with an unpleasant spring cold. So Mrs. Gaskell’s light (by comparison with Hardy) narrative has kept me company while sniffling and sneezing. All 600 pages in a little over 24 hours…

Though written a mere score or so of years earlier than Hardy’s works, Mrs. Gaskell is still smack in the middle of the religious mania that colours most mid-19th century novels. Her story was filled with scenes of professed Christians offering wise counsel to those who were reluctant to believe, and making amazing progress in their conversion through verbal argument. It’s also singular to see the import placed on small doctrinal differences, as Hardy did with Angel Clare in Tess nearly to the point of parody. It may seem a bit silly to us today, but at a time when nearly everything you did flowed out of your unquestioning faith, not only in God, but in the Church, it is understandable. Every loving hope rested on eventual reunion in heaven, and if you were taught that only some would be allowed to enter through those pearly gates, figuring out how to assure your place — and the place of those you cared for — became truly a matter of life and death.

Oddly enough, I didn’t cry for any of Hardy’s characters, though I felt their pain more sharply. I will admit however that I had tears running down my face at various points in North and South. Mrs. Gaskell, perhaps because her social message was a bit more subtle, refrained from the more extreme rhetoric that reduced me to pathetic sobbing while reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin (coincidentally another story of the North and the South), but she still managed to dwell overlong on certain scenes in a way that only mid-19th century lady authors seem able to do.

Sadistic Feminism

March 14th, 2011

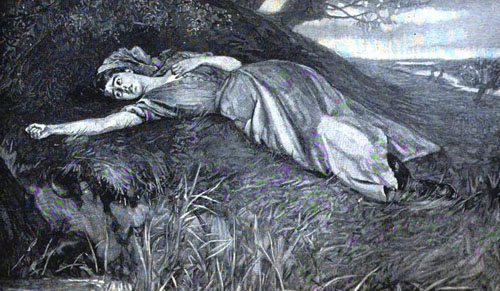

I have now read two novels by Thomas Hardy, and am convinced that, within the confines of accepted thought of his time, he was a rampant feminist. I may change my tune when I’ve had time and inclination to read further into his novels, but so far, both Bathsheba and Tess strike me as powerful advocates for their sex. M’hap not so much on their personal merits — the one a self-centered brat, the other an emotional simpleton — but as examples of the senseless harms perpetrated on the weaker sex by an unsympathetically masculine world.

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles particularly, one finds very little patience with any of the male characters. The stories of the women, from Tess and her relations, to the girls she labored with at the dairy and later the starve-acre farm, are all finely drawn and their trials wrought with such pathos as to tug at the heart of even the most chauvinistic reader. On the other side, we have only her shiftless father, lascivious “cousin,” and starry-eyed stripling of a husband. The sin that Tess must absolve with heart’s blood is caused by one man and shunned by another, and her ultimate punishment is exacted by a society founded on the prejudices of men.

Rather than rail at his readers, Hardy takes the subtle approach of engaging our sympathy. He presents the case without argument, trusting in the intelligence of some at least to make the leap. Or do I read too much into his fine storytelling? He could have simply written what he saw, and it is only my post-feminist sensibility that perceives any preference in the narrative.

I suppose I should first enlarge my base from which to pursue such conjecture by reading more of Hardy’s works. But I simply cannot undertake such just at present. Two in a row is more than anyone should have to take. Suffering is as suffering does. After finishing Tess yesterday, I was tempted to pick up Sons and Lovers, but forbore even that much and chose North and South by Mrs. Gaskell instead.

Hardy Explains Himself

February 25th, 2011

I’m about halfway through Tess of the d’Urbervilles, but I couldn’t resist sharing this line:

“the chronic melancholy which is taking hold of the civilized races with the decline of belief in a beneficent power.”

I’ve finally traced the well-spring of the despair that weaves through late 19th and turn of the century literature. And my long-time suspicions have been proven true!

You may laugh at my naiveté, but first consider that I missed out on all those comparative literature courses you had to suffer through. I’m seeing all this with fresh eyes and can’t help being a little bit excited.

For the record though, Tess is harder to read than Far from the Madding Crowd — it’s obviously further down the road of Hardy’s artistic development, and he has dared to put completely sympathetic characters in the path of dire and senseless misfortune. Harder to read isn’t always a bad thing though. Tess seems a more complex, complete work. And, so far at least, it abstains from self-consciously poking fun at itself, which, though fun to read, is the mark of an unsure author.

Ten points if any of you Jimmy Webb fans can figure out why I’m including this Art Garfunkel video in tonight’s posting.

Salome

February 21st, 2011

As the Gentleman and I were walking home from dining out last Friday evening, we passed a thrift shop just north of Washington Square Park. On a whim we ducked inside, and proceeded to spend a jolly quarter of an hour poking about, turning things over, and holding up outlandish outfits for the other one to wear. In the end, the only thing we could bring ourselves to actually buy was this 78 rpm double record of Strauss’s Salome, final scene. It features soprano Ljuba Welitsch with Fritz Reiner conducing the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

The cover is a bit beaten up, but the records themselves are as clean as if they’d hardly been played. At first I was astonished to find that a four record set contained only a single act of the opera (I have a 6 record LP set of Norma in its entirety that I invariably play during thunderstorms), but my cohort pointed out that they were 78s, and as such, each side only lasts about 4 minutes!

Although this is my first foray into Strauss’s opera, Salome has fascinated me for years. In case you haven’t already guessed, I am a great fan of Oscar Wilde. I don’t recall if I began with Dorian Gray or one of his many excellent plays, but I eventually came to his Salomé. To be quite honest, I found it a bit overdone at first (I was young), but upon learning that it had originally been written in French, I began to think better of it. And of course, there were the illustrations by Beardsley.

Beyond the literary import of Wilde’s Salomé, it also earned a place in the history of censorship and obscenity laws. Maud Allan, the dancer who dared to introduce a routine based on portions of Salomé to the British stage in the early 1900s, undertook an extensive legal battle to defend her good name from the “libelous” (and treasonous) charges leveled at her scantily clad dance of the seven veils by an ambitious MP in cahoots with the father of Wilde’s erstwhile “Boise”. For the full story on this, and how it dredged up a number of other scandalous issues in post-Victorian society, I heartily recommend Oscar Wilde’s Last Stand.You may also enjoy Alla Nazimova’s silent film version.

Any play that can provoke that much furor is deserving of its place in history!

You must admit, Maud Allan chose a rather shocking costume for 1908.